A 5th Israeli election in 3 years? Here’s how we got here and what happens next.

(JTA) — It has become a common refrain: Israel is heading towards another national election. A whopping five times since 2019, to be exact.

On Monday, Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid, the two men who had cobbled together a historically diverse coalition to oust Benjamin Netanyahu from power a year ago, announced that they will help fast-track a bill to dissolve the Knesset, or Israeli parliament. New votes will likely be cast in October.

Many readers have had the same questions: Why does this keep happening? What happens next? Could Netanyahu make a comeback?

Read on for the answers.

Why are Bennett and Lapid calling for new elections?

The short answer: they have lost their parliamentary majority after multiple politicians defected from their coalition.

The government, formed almost exactly a year ago, had a shaky foundation from its start, combining a slew of parties that historically would have not worked together: Bennett and Ayelet Shaked’s national religious Yamina, Lapid’s centrist secular Yesh Atid, the left-wing Meretz and the Muslim Arab Ra’am.

As soon as the new government was in place, lawmaker Amichai Chikli quit Bennett’s Yamina Party to join the opposition, citing the presence of Meretz and Ra’am in the government. That gave the Bennett-Lapid government a 61-59 majority, which lasted until April, when Idit Silman, also in Yamina, quit because of a court ruling allowing families to bring food that was not kosher for Passover into hospitals. That made it 60-60.

The final blow came as the result of behind-the-scenes maneuvering by former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has been leading the Knesset opposition and whose veteran politician wiles had helped him remain Israel’s leader for a record 12 years. Netanyahu, who reportedly had been meeting with Yamina members to try and lure them away, seized the opportunity to create a crisis.

Normally, he and his Likud Party would vote to extend Israeli legal protections to Jewish West Bank settlers. But Netanyahu realized that he could anger Yamina politicians by helping to tank the measure, which has been passed repeatedly since just after the 1967 Six-Day War. Without Likud votes and the votes of coalition members on the left who oppose the occupation of the West Bank, the extension did not pass, infuriating Yamina members and other right-wing politicians in parliament.

It was the ultimate example of an issue that split the coalition’s diverse parties into poles that could not be reconciled. Nir Orbach, another Yamina Knesset member who had been twisting himself into Hamlet-worthy knots since the coalition’s launch, finally defected. That left a 59-member coalition, an unsustainable number in the 120-seat parliament.

Why does this keep happening in Israel?

In a proportional representation system, no one party usually musters enough of a presence to lead a government on its own. Parties, and sometimes political rivals, need to come together to form coalitions that agree to work together to pass legislation; there is often just one ruling coalition and one opposition coalition.

For years, Netanyahu’s conservative coalition defeated any contenders, usually a mixture of liberal and more centrist parties, pretty soundly. But by 2019, Netanyahu had alienated some more traditionally conservative voters — and some of his political allies — after being indicted on multiple corruption charges, being seen as beholden to haredi Orthodox demands, and through a perceived imperiousness and willingness to shatter norms to stay in power. The schism gave centrist and liberal parties, led by former Israel Defense Forces chief Benny Gantz, an opportunity to challenge Netanyahu’s reign.

The final voter math, though, led to repeated deadlock; neither the Netanyahu or Gantz coalitions could eke out a firm majority. As the COVID-19 hit in 2020, Gantz said the pandemic required sacrifice and agreed to a unity government with a rotating prime ministership. Netanyahu dissolved the government before Gantz got his turn.

By last year, many politicians across the spectrum could not contemplate another minute of Netanyahu in power. Bennett, who made his name as a staunch settler supporter, and Lapid, a former TV anchor who is liberal on social issues but more hawkish on military issues, formed a historic coalition that included a majority Arab party for the first time.

Israel is not the only country with a parliament that has failed to form a government; for example, Italy has long been plagued with similar issues. But the vast array of conservative parties combined with Netanyahu’s polarizing modus operandi has made the proposition particularly difficult in Israel.

So what happens now?

Netanyahu, who has been champing at the bit for a chance to return to power, has immediately gone to work. In fact, the aforementioned Orbach chairs the Knesset’s procedural House Committee, and The Times of Israel reported that he is using his discretionary powers to delay the dissolution of parliament for a few days so Netanyahu could potentially form an alternative government based on parliament’s current makeup, without a need for new elections. Netanyahu currently can count on 55 of the Knesset seats.

Netanyahu getting to the 61 he needs is unlikely, however. Six members of the opposition are in the Arab-majority Joint List Party — and as frustrated as they were with the Bennett-Lapid configuration, many Arab lawmakers revile Likud and Netanyahu even more.

Additionally, the folks who hated Netanyahu — well, they still hate Netanyahu. Gideon Saar, who leads the six-member right-wing New Hope Party, told Army Radio that there was no way he would join a Netanyahu-led government. “I won’t be bringing Bibi back,” he said. “All of the party members are with me.”

Liberman, who heads the secular right-wing Yisrael Beitenu party, which has seven members, wants to go further: he is determined to pass a law before the next elections that would keep anyone under criminal indictment from becoming prime minister.

Even if that kind of bill becomes law, Netanyahu would still run, said Gideon Rahat, a political science professor at Hebrew University and a senior fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute. He could still lead the Likud Party and then repeal the law should he cobble together a majority in the new Knesset.

“Israeli politicians are always changing the rules of the game,” Rahat said. “It’s like changing the U.S. constitution for every immediate need, something that you wouldn’t imagine.”

Various Israeli TV channel polls show Netanyahu’s bloc earning 59 or 60 seats if a vote was held right now, just short of the 61 needed for a majority. It’s unclear what kind of group would reemerge to take Netanyahu on; Bennett is reportedly mulling a break from politics. Lapid’s Yesh Atid is polling at 20 seats, Gantz’s Blue and White at 9 and Yisrael Beiteinu at 5.

What does seem most certain for now: Lapid will take over as prime minister in the interim caretaker government, thanks to a clause written into his agreement with Bennett.

Can Lapid be a transformative prime minister in just a matter of months?

Probably not.

It is true that Lapid will be the first center-left prime minister since Ehud Olmert left office in 2009. Lapid is committed to a two-state outcome and rode to popularity as an outspoken opponent of the role of the Orthodox rabbinate in public life. As foreign minister, he has reversed Netanyahu policies, repaired ties with the American left and cooled down relations with European nationalists (which Netanyahu had strengthened).

Nothing will technically prevent Lapid from initiating bold, sweeping moves before elections take place. Legal restrictions on a caretaker government do not kick in until after election day. But in the past, according to the Israel Democracy Institute’s Assaf Shapira, attorneys general and Israel’s high court have limited what interim governments can and can’t do, citing norms that apply to lame duck administrations in democracies.

Lapid said in his statement he will pursue a robust foreign and domestic policy — he is keeping the foreign minister portfolio — and hinted that he will cast Netanyahu as a threat to democracy.

“Even if we are going to elections in a few months, the challenges we face will not wait,” Lapid said in a statement Monday. “We need to tackle the cost of living, wage the campaign against Iran, Hamas and Hezbollah, and stand against the forces threatening to turn Israel into a non-democratic country.”

Lapid will likely be in place as prime minister when President Joe Biden visits Israel in mid-July. It will be an occasion for Lapid to show how his government has moved past tensions with U.S. Democrats that flared when Netanyahu was prime minister.

Could this affect Israel’s stance on the Russia-Ukraine war?

The reason for Israel’s relative reticence in joining the U.S.-led isolation of Russia over its invasion of Ukraine has to do with security considerations, which in Israel transcend politics.

Russia, still present in Israel’s region after assisting the Assad regime in quelling Syria’s civil war, controls the airspace over Syria and Lebanon. Israel needs Russia’s approval for its airstrikes aimed at keeping enemies such as Iran, Hezbollah and Syria at bay.

But Lapid, at least rhetorically, has been more outspoken than Bennett in condemning Russia for its war. How he positions himself on this issue in the early days of his short PM stint could be telling.

Zelensky singles out Israel for refusing to join international sanctions against Russia

(JTA) — In a live streamed address to students, faculty and staff at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky urged Israel to join the network of countries around the world that have placed sanctions on Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.

“We are grateful to your great nation. But we would like to also get support from your government,” Zelensky said. “Tell me, how can you not help the victim of such aggression?”

In his address, Zelensky recognized the connected histories of Ukraine and Israel, noting the Ukrainian origins of Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem, Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, Zionist leader Zev Jabotinsky and many others.

He also noted that the Russian shelling of Ukrainian cities has affected many Jewish historical sites, such as the memorial at Babyn Yar, where at least 33,000 Jews were murdered by Nazis and their Ukrainian collaborators in 1941. At least five people were killed in the Russian shelling at Babyn Yar in March.

“The occupiers are not discretional in how they fight,” Zelensky said, adding that more than 2,000 schools have been targeted by Russian missiles and shelling, according to the Ukrainian government.

“This is about values and general security. Everyone who is willing to destroy another nation has to be held accountable,” he said. “Many European countries act together with us against Russian aggression. And unfortunately, we have not yet seen Israel join the sanctions regime.”

In a question and answer portion after Zelensky’s prepared speech, a student born in Ukraine asked whether Ukraine has received any support from international Jewish organizations to address the destruction of historic Jewish sites.

“We have received support from the Jewish Congress and U.S.,” Zelensky said. “I did want to have more of that support from the government of Israel on that particular question, because this is our joint sorrow, and that’s what it is. Just simply wanted to have more of it. But I’m not trying to hint at anything. It’s just as painful to us here in Ukraine as it is to Israel. This is a big tragedy. And I think I have nothing to add here.”

During the Q&A, another student told Zelensky that her father was fighting in the war. She asked whether the government of Ukraine would consider adopting a mandatory military service in the future, similar to the one that exists in Israel.

“This is one of the models that we are considering,” Zelensky said. “I’m not sure that this will be the exact model that we will follow, but it will be on the table and it will be discussed with the civil society.”

He added that even without a draft, Ukrainians already know how to fight. “They have been defending our country with no weapons, with bare hands — but now with weapons.”

Yishai Fraenkel, vice president of the university, asked what the future of Ukraine might look like when the war ends.

Zelensky said there are plans for post-war reforms and improved military defense systems, and emphasized a future with the European Union.

“We are moving towards a new civilization,” he said. “And we have sacrificed a lot for that. But the most important is that this is our choice.”

“Of course, we’re still very young, but first and foremost, this is for our children,” he continued. “So we will be building a European state, which will be part of the European Union.”

He added that Ukraine and Israel have “a great future” together.

“Please remember how much we are linked, how close our ties are,” he said. “I do care about our future relations between our states and our people. This is why I’m being sincere. And I’m sure that the war will end and we will win. And we do have a joint future. A great future.”

How this kosher, gluten-free bakery creates some of New York’s tastiest bagels

(New York Jewish Week) — Orly Gottesman began experimenting with gluten-free baking as a labor of love when her then-boyfriend, now-husband Joshua Borenstein was diagnosed with celiac disease in 2007. Over the ensuing decade, she grew from a hobbyist to a skilled baking professional, selling her unique gluten-free flour blends to various bakeries and home bakers around the country.

But Gottesman really found her groove in 2018, when the couple were visiting family in New Jersey and decided to take a trip to the Upper West Side. There, near the corner of 82nd Street and Columbus Avenue, they passed a bagel shop for rent.

“I think we should take this,” Borenstein told Gottesman. “You have all these people buying your flour blends and bakeries using your blends. No one can execute the final product the way you can.”

It was then that the idea for the gluten-free and kosher restaurant and bakery Modern Bread & Bagel was born. The eatery opened at 472 Columbus Ave. in February 2019 and now turns out some 2,250 gluten-free bagels every day to rave reviews. Former New York Times restaurant critic Mimi Sheraton once wrote that a good bagel should give your jaw “a Sunday-morning workout” — thanks to an intense chew that’s almost always courtesy of high-gluten flour — Modern Bread & Bagel’s gluten-free bagels prove there are exceptions to the rule.

In fact, its bagels have been named among the best in the city by no less an authority than Mike Varley, an intrepid New Yorker who recently published the results of a massive bagel tasting project, Everything Is Everything. After sampling and reviewing bagels from 202 shops during epic treks through the five boroughs, Varley placed Modern Bread & Bagel in a tie for third place for all of New York, and ranked it the second-best bagelry within the borough of Manhattan.

“The store experience is wonderful, it’s clean and contemporary,” Varley told the New York Jewish Week about Modern Bread & Bagel. “The staff is warm and welcoming and the bagel itself has a different quality to regular bagels. It is doughy and crusty. The topping composition is fantastic. And the fact that it doesn’t contain gluten makes for a much less heavy experience.”

Gottesman relished the review. “It was a real testament to accomplishing our mission of opening a bagel shop that ‘just so happens to be gluten-free,’” she said. “The bagels are what put us on the map.”

While “gluten-free” has evolved into something of a buzzy health trend — similar to the “fat-free” craze of the 1990s — the need for gluten-free products originates from a very real medical condition: celiac disease, in which the body has an immune response to gluten. When Borenstein was diagnosed it was relatively rare, though awareness of celiac disease has grown markedly since then. According to recent estimates, more than 2 million Americans have the condition.

Back in 2007, however, the celiac diagnosis was devastating to then 20-year-old Borenstein. “Josh told me he was lucky to have met me before all this happened,” Gottesman recalled. Borenstein, said Gottesman, is “a real foodie” whose family owns Chompie’s, a chain of bagel restaurants in Arizona. Having celiac signaled the end of his consumption of any sort of wheat product.

But Gottesman wasn’t ready to give up on Borenstein’s love of bagels. By 2010, the couple were married and living in Paris for Borenstein’s job. Gottesman didn’t speak French and didn’t have a work visa — and therefore had a lot of time on her hands. “I thought, when in Paris, take baking,” she said. Gottesman found an English-speaking patisserie owner and she took baking classes there.

Gottesman was a natural and eventually became the shop owner’s apprentice. After about a year, she decided to enroll in culinary school — landing at the Cordon Bleu Culinary Arts Institute in Sydney, Australia, where the couple relocated, again for Borenstein’s work. The move to Sydney “ended up being a blessing in disguise,” Gottesman said. “The program in Australia was so much more open to me exploring the gluten-free side of baking than was the Paris program.”

By 2014, Gottesman had completed her baking studies and moved to Arizona for a year to develop gluten-free products for Chompie’s. She created a line called Orly the Baker and made gluten-free bagels, challah rolls, rugelach, babka and cookies.

She returned to Australia in 2015 and worked in a commercial bakery, wholesaling a variety of gluten-free items for local bakeries and cafes. At the same time, she developed a line of gluten-free flours, Blends by Orly, designed to be used for a variety of different baking applications. She introduced her line of specialized flours to the market by traveling to the United States regularly to participate in trade shows and cooking demonstrations.

Before opening Modern Bread & Bagel, Orly Gottesman developed a line of gluten-free flours, Blends by Orly, designed to be used for a variety of different baking applications. (Courtesy Modern Bread & Bagel/Facebook)

But when the couple stumbled across that for-rent sign in Manhattan, they decided it was time to open their own shop. They both felt that the Upper West Side was the right place to start. “It has a big Jewish customer base and we are dealing with bagels and Jewish food,” Gottesman said. They decided to make Modern Bread & Bagel kosher to further “reflect our values,” she said.

Gottesman’s bagels are made from her Manhattan Blend, which contains the ancient grains millet and sorghum. This particular gluten-free flour variety includes high-protein, gluten-mimicking ingredients, and she adds xanthan gum to the mix to give stretch to the dough.

The amount of water Gottesman uses in her bagel dough is also carefully calibrated. “If there is too much, it becomes fluffy. Too little will make it dry. You need the right balance of water to dough to yeast ratio,” she said. It took Gottesman three years to develop the right proportions.

Gottesman’s efforts paid off, and Modern Bread & Bagel now fills an important niche. Jessica Hanson is a celiac disease advocate who was diagnosed 11 years ago, and she clearly remembers what “regular” bagels taste like. “We are a family that really loves bagels,” she said. “When I was diagnosed with celiac disease I mourned the loss of bagels.”

Hanson, who lives in Woodside, Queens, considers Modern Bread & Bagel “a magical place.” As she told the New York Jewish Week: “My husband eats gluten and he absolutely loves bagels as well. He can’t tell the difference between that and a gluten-containing bagel.”

“People with celiac disease are used to having to ask a million questions about food preparation,” Hanson added. “When you get something that is so specific to family, culture and NYC and you know it is safe to eat, that’s really meaningful.”

For Gottesman, who now lives in Englewood, New Jersey, such accolades represent the fulfillment of a long-held dream. “It was really important to us to have a space that does not stigmatize gluten-free food,” she said. ”There are times that I get really jaded and discouraged. This is a hard business. But then you hear from people that this product is changing their lives. They are so appreciative.”

Just as the gluten-free bagels are a savior to celiac disease sufferers, during the pandemic lockdown the bagels also saved Gottesman’s business. “We became inundated with people asking if we could ship the bagels to them,” she said. “The bagels were the focal point of our business. They set us apart.”

These days, Modern Bread & Bagel sell out of their bagels nearly every day — thanks to a combination of in-store orders, mail order and orders from her wholesale clients, Black Seed Bagels and Ess-A-Bagel. A second Manhattan Modern Bread & Bagel location opened earlier this month on West 14th Street, and a third location will follow in Woodland Hills, California next month.

“Everyone wants to do something in their lives that is meaningful,” said Gottesman. “The series of events that happened in my life, from meeting Josh to his celiac diagnosis to our travels around the world, culminated in this moment.”

“God,” Gottesman added, “has a plan.”

24 Democratic senators urge Biden to involve US in investigation of Palestinian journalist’s death

(JTA) — Just under half of all Democratic senators are seeking the “direct involvement” of the United States in the investigation of the death of a Palestinian journalist who was shot over a month ago while covering an Israeli raid on a West Bank refugee camp.

Twenty-four senators signed a letter sent to President Biden Thursday, three weeks prior to his first scheduled state visit to Israel. It is the largest action yet from U.S. lawmakers seeking an independent resolution to the May 11 killing of Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, who was an American citizen. Multiple media investigations have independently concluded that she was most likely killed by Israeli soldiers, with The New York Times this week joining the Washington Post, the Associated Press and CNN in reaching the conclusion.

“We believe that, as a leader in the effort to protect the freedom of the press and the safety of journalists, and given the fact that Ms. Abu Akleh was an American citizen, the U.S. government has an obligation to ensure that a comprehensive, impartial, and open investigation into her shooting death is conducted — one in which all parties can have full confidence in the ultimate findings,” reads the letter, which was spearheaded by Maryland Sen. Chris Van Hollen.

The letter adds that U.S. intervention is needed because “it is clear that neither of the parties on the ground trust the other to conduct a credible and independent investigation.” The Palestinian Authority has accused the Israeli military of intentionally targeting Abu Akleh, a claim fiercely disputed by Israel; Israel has said it needs the Palestinian Authority to hand over the bullet that killed her in order to complete its investigation.

Jewish senators who signed the letter include progressives Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Brian Schatz of Hawaii. Other notable signatories include Raphael Warnock of Georgia, Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. The letter is also addressed to Jewish Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Jewish Attorney General Merrick Garland and FBI Director Christopher Wray.

The letter follows an earlier bipartisan letter from Jewish Democratic Sen. Jon Ossoff and Republican Sen. Mitt Romney that also urged the U.S. to play a more active role in an Abu Akleh investigation, as well as two letters from the House: one from 57 House Democrats that called for an FBI investigation and another, bipartisan letter that pushed the Palestinian Authority to hand over the bullet.

Haaretz reported that AIPAC, the powerful pro-Israel lobbying group, had distributed talking points intended to squash the latest Senate letter on Abu Akleh. According to AIPAC, the letter “implies both Israeli culpability and inability to conduct an objective, thorough investigation of the incident.”

Abu Akleh’s killing and its aftermath have created an international firestorm and further inflamed already deadly tensions between Israelis and Palestinians. Israeli police almost toppled her coffin when they charged mourners who turned her funeral into a protest, and the delayed official Israeli investigation has upset many outside observers.

Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, who recently called for new elections after his coalition in the Knesset dissolved and has hinted he will not run again, told The Times this week that he did not know who fired the bullet that killed Abu Akleh. Bennett said, “What I do know is that Israeli soldiers definitely do not shoot intentionally. Never will Israeli soldiers intentionally target reporters.”

The Vatican will release WWII-era ‘Jewish files’ online, including unanswered pleas to the pope

(JTA) — Pope Francis has ordered 170 volumes of Jewish requests for help from the Catholic Church during World War II to be published online, two years after making their physical copies available to historians.

His decision is the latest development in the Vatican’s newfound reckoning of its legacy during the Holocaust.

The correspondence contains 2,700 files specifically recounting Jewish groups and families requesting assistance from the Vatican in avoiding deportation or trying to free relatives from concentration camps, both in the run-up to and during the Holocaust. Pope Pius XII, who served as pope during the most pivotal years of the war, is often charged by historians with ignoring Jewish pleas for help and cozying up to Hitler and Mussolini in order to preserve the influence of the Church.

The Vatican itself has long insisted that Pius XII should be celebrated for secretly advocating for Jews via diplomatic means, but that narrative is changing as more information about his papacy has been revealed to the public. The Church opened its secret files on Pius’s archives to historians in 2020, but by publishing its Jewish-related files online, it opens them up to easier access and greater scrutiny by the public.

“The Pope at War,” a new book by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David Kertzer, the son of a rabbi, draws on these new archives to make the case that Pius largely ignored pleas from Jews (while keeping a secret back channel to Hitler). Pius did, however, concern himself with trying to save the small number of Jews who had converted to Catholicism or who were from mixed families, categories that were still considered “Jewish” under Hitler’s racial laws.

Paul Gallagher, the Vatican’s foreign minister, wrote in a church newspaper that the digital release of the files was also intended to help provide closure to the descendants of Jews who had implored the Vatican for help.

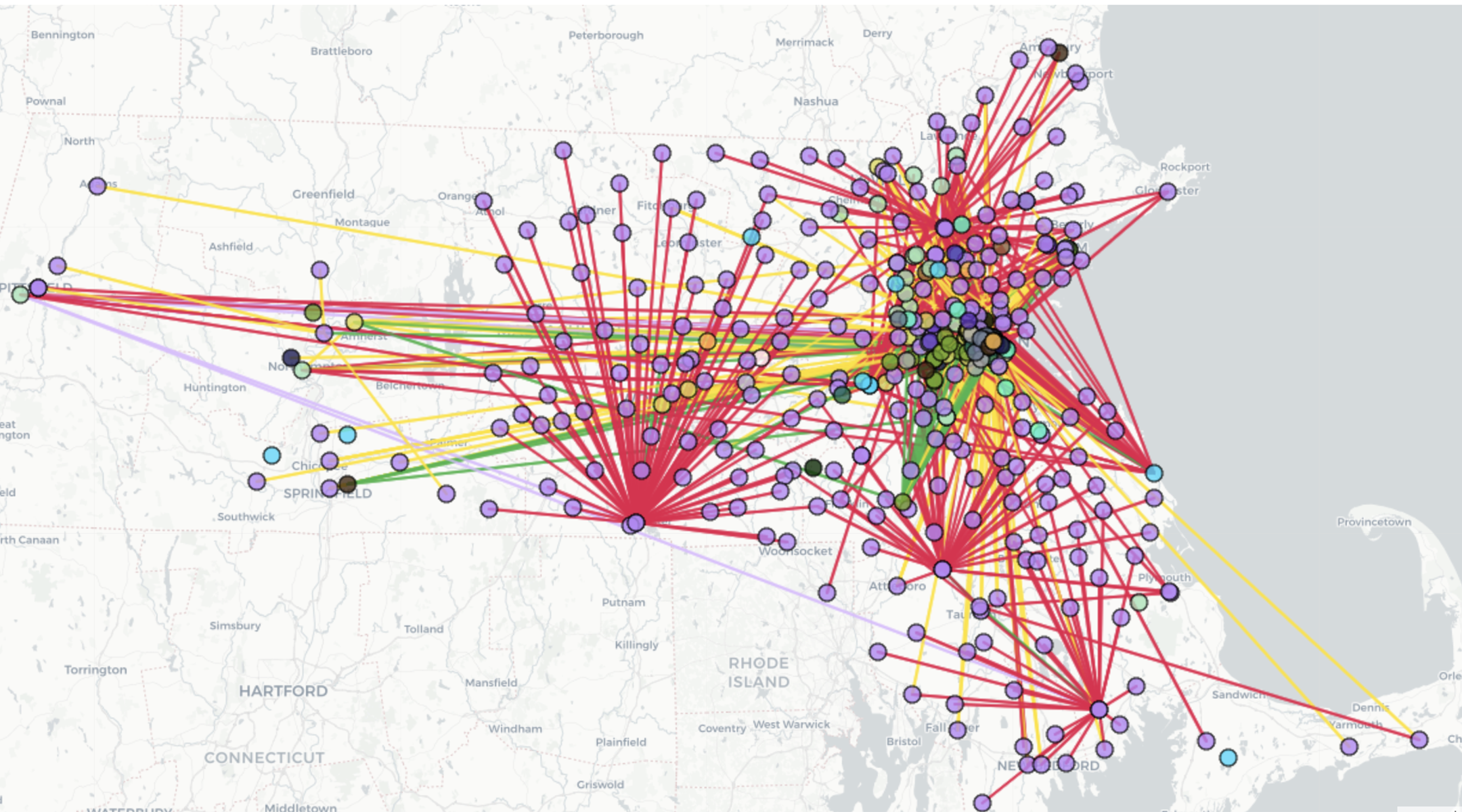

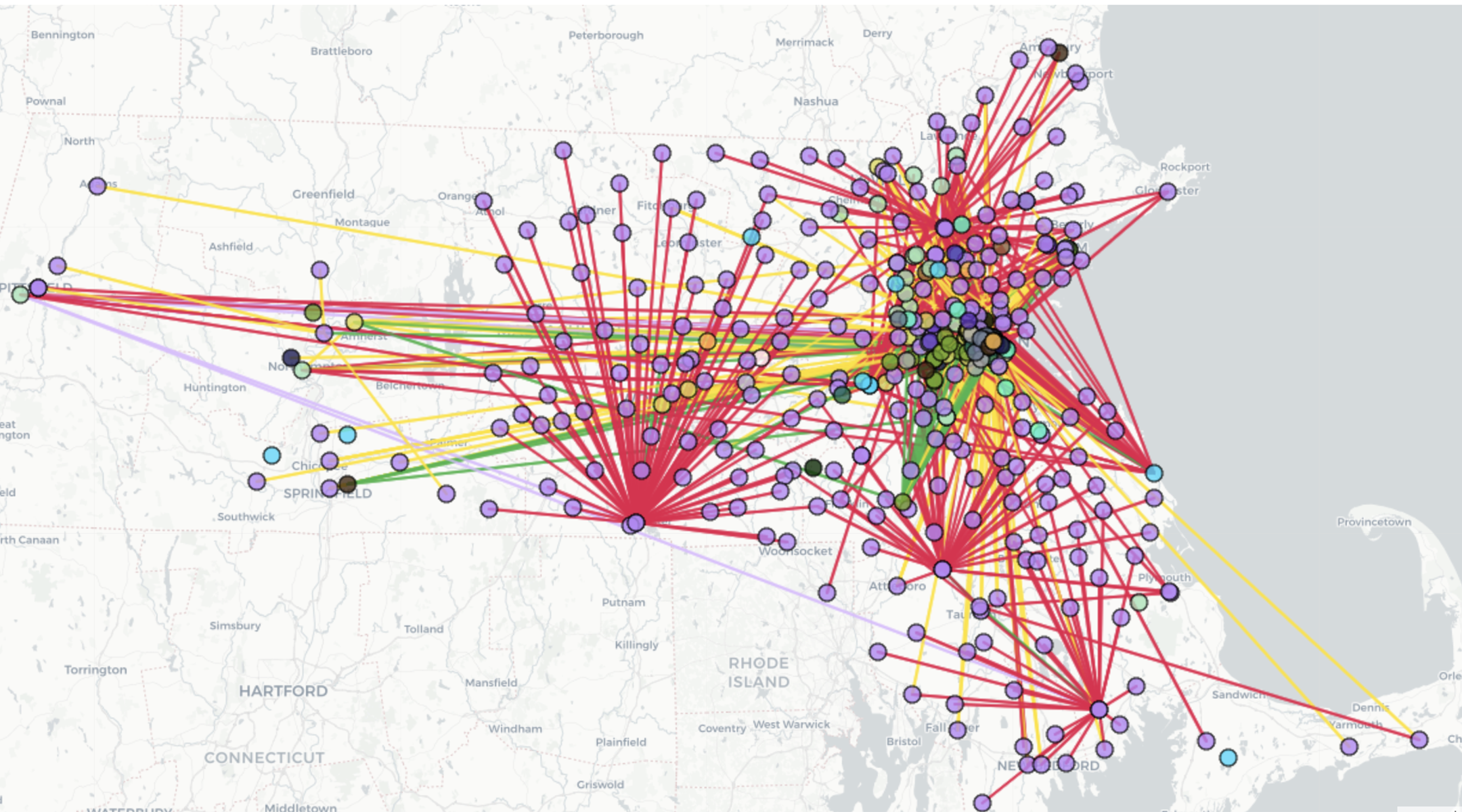

BDS movement disavows Boston project mapping Jewish groups as some in Congress push for a federal investigation into its use

(JTA) – The global Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement targeting Israel has disavowed a controversial website mapping Boston-area Jewish groups a day after lawmakers urged a federal investigation of the project’s potential to be used by extremist groups.

The announcement by the BDS movement on Wednesday aimed to distance the group from the Mapping Project, an anonymous collective of Boston-area pro-Palestinian activists. The project lists the names and addresses of Massachusetts Jewish groups, including schools, community funds and synagogue organizations, that it claims are promoting “local institutional support for the colonization of Palestine” and “other harms.”

“The Palestinian BDS National Committee, the broadest coalition leading the global BDS movement for Palestinian rights, has no connection to and does not endorse the Mapping Project in Boston, Massachusetts,” the BDS movement said in a statement posted to its official Twitter account. “Endorsement of this project by any group affiliated with the BDS movement conflicts with this affiliation.”

The collective’s statement seems to be in reference to BDS Boston, which had enthusiastically shared a link to the Mapping Project upon its initial release earlier this month and identified the group as “our friends at the Mapping Project.” This led several media outlets, Jewish groups and politicians to identify the Mapping Project as a BDS initiative.

In a letter to BDS Boston dated June 20 and obtained by the Jewish Journal’s Aaron Bandler, the broader BDS movement urged the Boston group to stop promoting the Mapping Project, which it said “present(s) a substantial risk” to the movement because of its targeting of institutions and individuals.

BDS also accused BDS Boston of running afoul of BDS guidelines by “promoting messaging which indirectly advocates for armed resistance and associating with groups that do.” (On its website, the Mapping Project calls for “resistance in all its forms.”)

Mahmoud Nawajaa, general coordinator of the BDS National Committee, told BDS Boston to either stop promoting the Mapping Project or remove BDS from its group’s name.

Among the politicians who associated the Mapping Project with BDS directly were the 37 members of Congress, led by staunchly pro-Israel Democrat Josh Gottheimer of New Jersey and Republican Don Bacon of Nebraska, who signed a letter Tuesday urging an investigation of “the use of the Mapping Project by extremist organizations.” The letter was addressed to Attorney General Merrick Garland, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas and FBI Director Christopher Wray, and it claimed the Mapping Project was “associated with the BDS movement.”

A map of purported connections between Jewish groups and other organizations in Massachusetts created by progressive activist group The Mapping Project, which says its goal is to map ‘institutional support for the colonization of Palestine.” (Screenshot)

“We fear that this map may be used as a roadmap for violent attacks by supporters of the BDS movement against the people and entities listed therein,” the letter says, while noting that the FBI “is already tracking developments.” Signatories included some of Congress’ most vocal pro-Israel voices on both sides of the aisle, including Reps. Haley Stevens, Ritchie Torres and Dan Meuser, as well as freshman Democrat Shontel Brown, who won her close Ohio race last year with the help of pro-Israel groups.

The letter followed an earlier round of condemnations from mostly Massachusetts politicians, including both of the state’s Democratic Senators and progressive Squad member Rep. Ayanna Pressley. Local Jewish groups including the New England Anti-Defamation League and the Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Boston, who were named on the project’s website, said the project was a deliberate effort to target Jews and could encourage antisemitic extremist acts.

In the same statement in which it condemned the Mapping Project, the BDS movement also condemned “the cynical use of this project as a pretext for repressive attacks on the Palestine solidarity movement,” singling out the ADL and AIPAC as “apologists for Israeli apartheid.”

The Mapping Project itself has not returned multiple Jewish Telegraphic Agency requests for comment.

For its part, BDS Boston continued to buck the national movement by supporting the Mapping Project on its own social media account, pinning its initial “Friends” tweet to its profile page and retweeting support of the project from other activist groups.

“BDS Boston continues to feel that the Mapping Project is an important source of information and useful organizing tool,” the group said in its own statement Wednesday, while also stating that the group “is its own collective that works autonomously from BDS Boston.”

Shoshana Akabas Barzel, 30, connecting neighbors with refugees

Shoshana Akabas Barzel, the founder and executive director of New Neighbors Partnership, a non-profit that welcomes refugee families by matching them with local families, was selected as one of the New York Jewish Week’s 36 to Watch (formerly 36 Under 36). This distinction honors leaders, entrepreneurs and changemakers who are making a difference in New York’s Jewish community. Akabas Barzel lives on the Upper West Side.

For the full list of this year’s “36ers,” click here.

New York Jewish Week: Tell us a little bit about your work.

Akabas Barzel: New Neighbors Partnership reimagines in-kind donations by turning what is normally a one-time blind donation into a long-standing relationship between families. In this model, newly arrived families are matched with local families who have slightly older kids, so clothes go directly from the local families that have them to the refugee families that need them. By matching families, we ensure newly arrived families will have a source of kids’ clothes for years to come. After three years of running this program as a community initiative on the side of my teaching and writing job at Columbia University, I turned it into a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. We have welcomed more than 350 children from 34 countries with over 1,500 clothing packages.

How does your Jewish identity or experience influence your work?

The Jewish value of welcoming the stranger was instilled in me from a young age, so my work at New Neighbors Partnership feels like a natural extension of that foundation.

Was there a formative Jewish experience that influenced your life path?

One experience was attending Beit Rabban, a pluralistic Jewish day school on the Upper West Side that was so welcoming and open, and prepared students to be deep thinkers and creative problem solvers.

What is your favorite place to eat Jewish food in New York?

My grandmother’s house!

Want to keep up with stories of other innovative Jewish New Yorkers? Click here to subscribe to the Jewish Week’s free email newsletters.

Deborah Lipstadt’s first tour as antisemitism monitor will be to Saudi Arabia

WASHINGTON (JTA) — Deborah Lipstadt’s first overseas tour as the State Department’s antisemitism monitor will start in Saudi Arabia, a signal of the kingdom’s efforts to change its image in the West and among Jews.

Lipstadt who was confirmed to the ambassadorial post in March said she proposed the visit to the Saudis, who were immediately receptive. She saw it as an opportunity to reach a nation influential in worldwide Muslim education because of its wealth and its status as the land of Islam’s holiest sites.

She said she hoped to meet with political, religious and civil society leaders.

“To talk with them about normalizing the situation of, the vision of the Jews, normalizing the understanding of Jewish history for their population, particularly the younger — not only, but particularly with a younger population — is really important,” Lipstadt said at a June 18 briefing with Jewish media at the State Department. “It makes a statement about the change.” The department embargoed the briefing until the dates of the 11-day trip, starting June 26, were finalized.

Lipstadt credited the Abraham Accords, the normalization agreements between Israel and four Arab countries, for making such a visit possible.

“If you had told me a year ago, even after the Abraham Accords, that would be the first place I would go. I would say you’re dreaming,” she said.

Lipstadt will also visit Israel and the United Arab Emirates, one of the Abraham Accords signatories. Her tour comes ahead of Biden’s visit to the region next month. Biden will visit Israel, the West Bank and Saudi Arabia, where he will attend a meeting of the GCC+3, the grouping of the Sunni Arab Gulf Cooperation Council states, and Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq.

Much of the West and especially the Democratic Party establishment remains wary of Saudi Arabia and its de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, because of its role in the bloody war in neighboring Yemen and the 2018 murder in Turkey of U.S.-based journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Jewish groups harbor memories of the Saudis leading hostile anti-Israel and anti-Jewish policies through the 1980s.

Saudi Arabia has in recent months launched an intensive image-improving campaign, most notably setting up an alternative to the golf world’s PGA tour. It has also reached out in recent years to Jewish groups, last week hosting a group of 13 Jewish leaders, including six senior New York UJA-Federation leaders, for a short visit.

Lipstadt at her briefing also described a meeting she convened last week of her counterparts from around the world, including from Germany, the European Union, Israel, Britain, and Canada. She said the exchange of ideas was fruitful and she hoped to convene it “regularly, every two, three months, four months.” “We can learn from one another,” she said.

Lipstadt, who when she campaigned for President Joe Biden suggested the Trump administration displayed fascistic tendencies, said at the briefing that it was critical to convey to populations how antisemitic theories portend trouble for all groups and for democracy. She also said the reverse is true — conspiracy theorists frequently end up embracing antisemitic tropes and endangering Jews.

Antisemitism “creates a lack of distrust in government, because if you feel that there is a group controlling the media, controlling the judiciary, controlling the banks, controlling the government agencies, why should I trust them? Why should I trust the democracy?” she said. “Antisemitism is the canary in the coalmine.”

Lipstadt said her next trip later in the year would be to Argentina and Chile. In Argentina, she hopes to bring back into the spotlight the unresolved 1994 bombing attack on AMIA, the Jewish community center in Buenos Aires, which killed 85 people.

In Chile, she said, she will speak with Jewish community leaders who are “feeling under pressure” since the election because of pressure on the community from the president, Gabriel Boric, to criticize Israel.

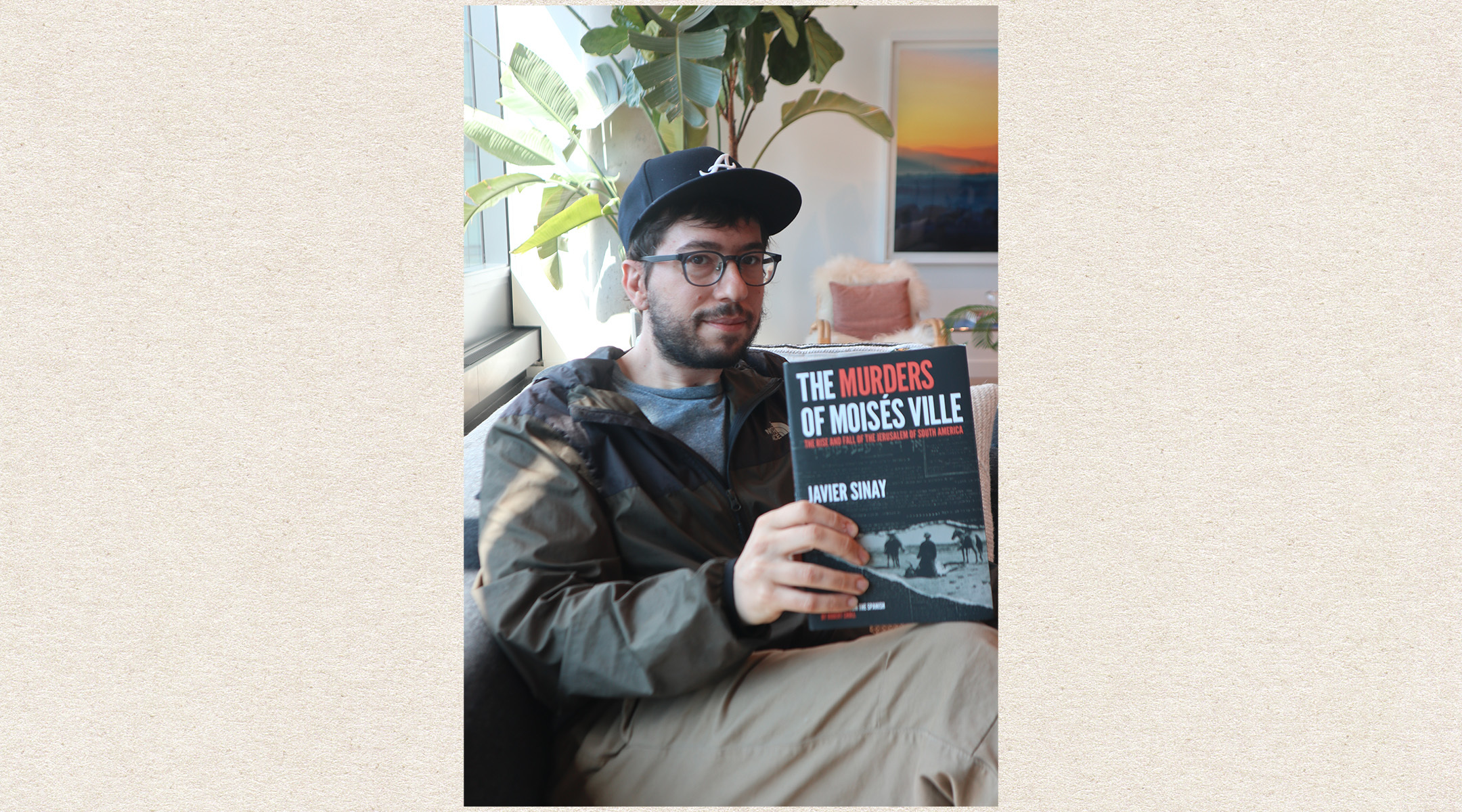

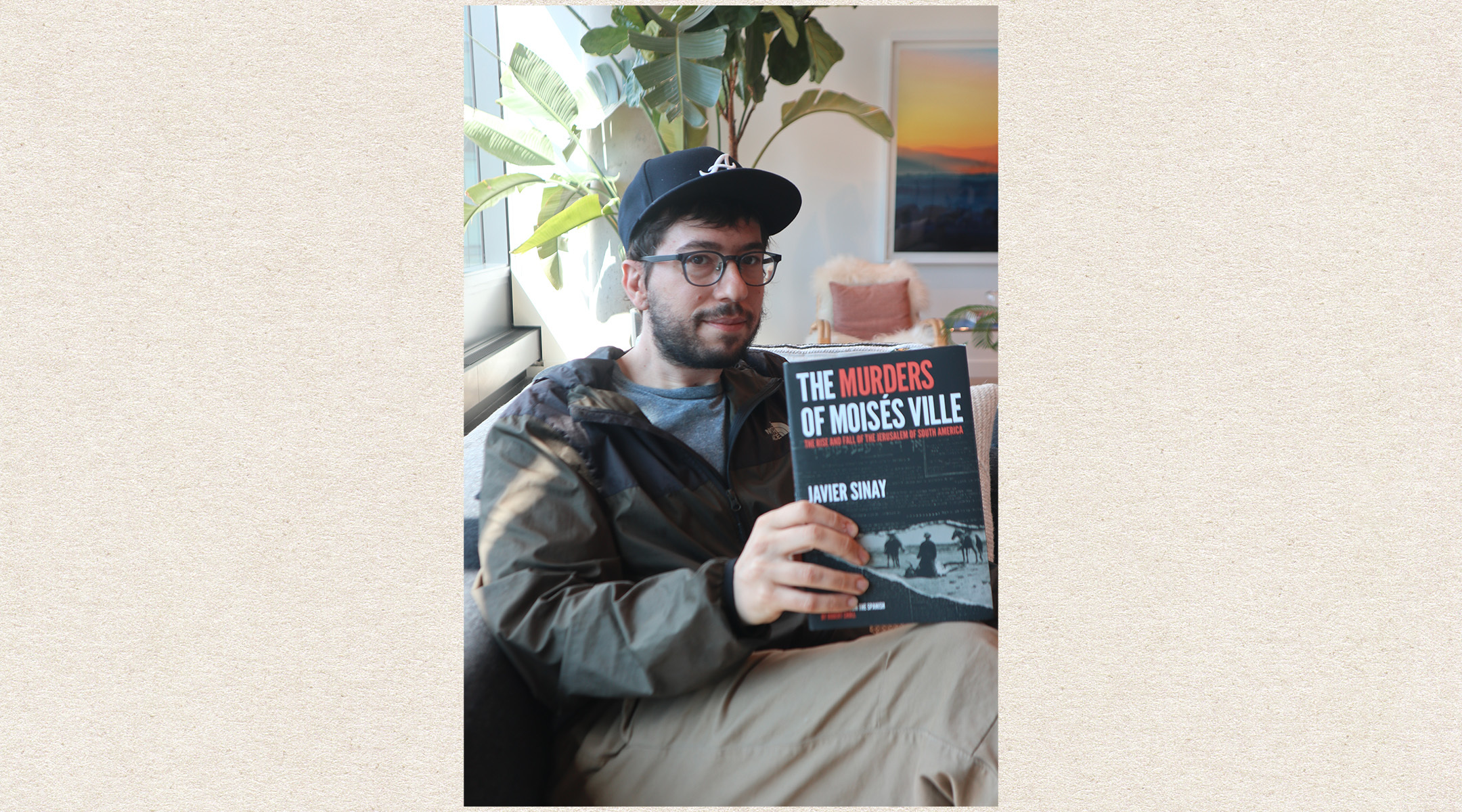

How the murders of Jewish farmers connected an Argentine writer with his family’s past

(JTA) — On June 9, 2009, Javier Sinay’s father sent him an email with the subject line “Your Great Grandfather.” The email linked to a Spanish translation of an article written in 1947 by Mijel Hacohen Sinay.

“The First Fatal Victims in Moises Ville” detailed a series of murders that had occurred in that village, the first rural Jewish community in Argentina, between 1889 and 1906. All the victims were recent Jewish immigrants, murdered by roving gauchos preying on their vulnerability.

“Reading this article raised many questions,” Sinay, an investigative journalist from Buenos Aires, explained in an interview with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in New York during his recent book tour. “Why did my great-grandfather report on murders that were committed half a century earlier? Who were the people murdered? And why?”

One question led to another, and consequently Sinay started his own investigation, one that turned into something much bigger and deeper.

The result is “The Murders of Moises Ville,” a book that goes beyond true crime to become a history of Jewish migration to Argentina, as well as a travelogue of Sinay’s visits to Moises Ville, retracing his own family roots. A surprise success in Argentina, the book had three print runs and launched a national debate about collective memory in a society that often prefers to bury the past. It was published earlier this year in English by Restless Books.

The village of Moises Ville, where the murders occurred, is located around 400 miles north of the Argentine capital Buenos Aires. For Argentine Jews, it is a mythical place, to which they attach feelings of nostalgia like those American Jews feel for Manhattan’s Lower East Side. However, as Sinay underlines, “its history is unique since Argentina has the only Jewish community that started as an agricultural community.”

Fleeing poverty and pogroms, hundreds of thousands of Jews left Czarist Russia at the end of the 19th century. Munich-born philanthropist Baron Moritz von Hirsch founded the Jewish Colonization Association, which facilitated their resettlement in Latin America under the theory that Jews who lived in small shtetls would find it easier to become farmers in the New World than resettle in urban areas. However, as the books publisher puts it, “like their town’s prophetic namesake, these immigrants fled one form of persecution only to encounter a different set of hardships: exploitative land prices, starvation, illness [and] language barriers.”

The first residents of Moises Ville were a group of families from Bessarabia and the Podolia region in today’s Ukraine. The village would soon become the cultural center of Jewish life in Argentina. Among the founders were Sinay’s great-grandfather, Mijel Hacohen Sinay, who arrived in 1894, and Alberto Gerchunoff, who in 1910 would publish “Los Gauchos Judios” (“The Jewish Cowboys”), a collection of short stories set in a village inspired by Moises Ville. Gerchunoff’s book is considered the first Latin American literary piece focusing on Jewish immigration to the New World.

However, by the time the book was published, the majority of Jews had already moved to Buenos Aires, among them Mijel Hacohen Sinay and Gerchunoff, whose father was one of the people murdered in Moises Ville.

The 42-year old Javier Sinay was born and raised in Buenos Aires. When he first learned about the murders, he did not know much about Moises Ville or his family’s history.

“I always knew I was a Jew, but I was not raised in Jewish environment,” said Sinay, who started to work on this book when he was 28. “It felt like an ancient call to learn about my ancestors. I found myself a link in a chain.”

This chain did not only relate to his Jewishness, but also to his love for journalism. “Before I started my research, I did not know that I come from a family of journalists, tracing back to my great-grandfather, the protagonist of my book.”

In 1898, Mijel Hacohen Sinay founded Argentine’s first Jewish newspaper, the Yiddish language Der Viderkol (The Echo).

“He was barely 20 years old. Discovering this was just incredible,” Sinay said.

Sinay himself has worked for the newspapers La Nación and Clarín and as editor at the Argentine edition of Rolling Stone. He is currently a staff writer for REDACCION.com.ar, a solutions journalism news outlet.

Javier Sinay book about Moises Ville and his family’s history was a surprise success in Argentina, where it went through three print runs . (Julian Voloj)

To read his great grandfather’s work, however, Sinay had to overcome a language barrier. To learn Yiddish, he went to the Fundacion IWO, the South American counterpart of YIVO, the New York-based YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. “I didn’t even know how to read Hebrew letters,” he said.

He soon was able to read newspaper headlines and book titles in Yiddish, but despite his progress, “it was not enough to translate whole articles by myself.” Sinay was introduced to Ana Powazek de Breitman, known to her friends as “Jana,” the daughter of two Holocaust survivors from Poland, who would help him with the translations.

“I would go to the warehouse of Tzedek [a Buenos Aires Jewish charity] and look for old Yiddish books. If it looked like there could be something interesting for my research, I’d buy the book and give it to Jana to translate. She would read for me in Yiddish, then translate into Spanish while I typed up notes.” For four years, they would meet twice a week.

Original copies of his great-grandfather’s newspaper had been stored in the building of Argentina’s Jewish federation, AMIA, which was destroyed in 1994 in a terrorist attack. “The AMIA bombing is a very traumatic for all of Argentine Jewry, but nearly made my research impossible. It underlines that it was also the destruction of a culture,” said Sinay. Some newspapers survived and were part of an exhibition at the National Library of items rescued from the terrorist attack. However, after the exhibition, even those papers disappeared. Sinay hired a private investigator to find them, but until now, nothing was unearthed. “But I have not given up hope.”

The highlight of his investigation was his journey to Moises Ville. “I think I was the first one of the Sinays who went back after my family ended up in Buenos Aires,” he said.

Today, Moises Ville has just over 2,000 residents, about 10% of them Jewish. Jewish sites there include the Kadima cultural center, which contains a theater and library; the former Hebrew School, Argentina’s first Jewish cemetery and three synagogues. A particularly meaningful experience for Sinay was spending Shabbat in Moises Ville at one of the local synagogues.

The Workers’ Synagogue (Arbeter Shul) in Moises Ville, Argentina, photographed in 2010. (Wikimedia Commons)

“I had never gone to synagogue before. I celebrated my first Kabbalat Shabbat in Moises Ville. It was a fascinating experience. I was thinking about my ancestors and about what kind of Jew I am. My upbringing has little in common with these immigrants, but I feel very connected to them,” he said.

“The Murders of Moises Ville” sheds light on a chapter in Argentina’s history that was widely forgotten.

“There is a romanticized image of immigration, but the reality was brutal,” Sinay explained. Although he was not able to find all the answers he was seeking, he believes that he understood why his great-grandfather wrote about the murders more than half a century after they took place.

“He wrote about the murders just after the Second World War, in a time of collective mourning. It was a catharsis remembering the dead, and even if it was not related to the Holocaust, it was part of the zeitgeist. He was talking about our history and our suffering. I don’t know if it is true, but it’s a theory I have,” he said.

Connecting as a reporter with his great-grandfather’s work is also a homage to the power of journalism, he said. “There is a lot of chaos in today’s journalism, but it is still possible to find good and meaningful stories that become our legacy.”

Reflecting on his own identity, he concluded: “I didn’t have a bar mitzvah, but maybe writing this book and reclaiming my Jewish identity through journalism was my bar mitzvah. And it’s something I have chosen, not something that was forced on me.”

A new book explores abusive rabbis and the Jewish institutional culture that protects them

(JTA) – In the global reckoning with sexual abuse by powerful leaders, no religious movement has escaped scrutiny and censure, including the broad spectrum of Jewish denominations.

Major Reform and Conservative bodies have mounted investigations or issued detailed reports on abuse and cover-ups within their ranks. Lawsuits have been brought against longtime accused abusers such as Baruch Lanner and institutions such as the Orthodox Union for protecting them. The rabbi heading Germany’s largest Liberal Jewish group recently took a leave of absence following allegations he had ignored or covered up harassment allegations leveled at his husband. Orthodox leaders in Canada and Australia who sheltered in Israel for years to avoid being tried on multiple counts of child sex abuse have been arrested, and are now awaiting trial in their home countries.

Jewish anthropologist, educator and activist Elana Sztokman has been researching the specter of rabbinical abuse for years. Her new book “When Rabbis Abuse: Power, Gender, and Status in the Dynamics of Sexual Abuse in Jewish Culture” is an effort to peel back the curtain on abusive power dynamics across every denomination. She is publishing it through Lioness Press, a feminist imprint she founded.

“We have lots of communal studies of engagement and continuity and belonging and all kinds of stuff, but not a single one has ever examined the connection between experiences of abuse and people dropping out” of Judaism, Sztokman told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “And that’s a big, gaping hole.”

Sztokman, who received her master’s degree and PhD from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has twice won National Jewish Book Awards for her books exploring gender dynamics in Orthodox spaces. She also recently spoke up about alleged workplace abuse she experienced, by a former board chair of the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance, where Sztokman formerly served as executive director.

While not a quantitative analysis, Sztokman’s book is informed by her interviews with 84 survivors of alleged abuse, and includes around 200 additional survivor testimonies gleaned through various Jewish archives. “When Rabbis Abuse” attempts to understand the manipulative personality type of abusive clergy, their methods and means of exploiting victims within Jewish spaces, and the ways in which their behavior is protected or excused by Jewish power structures.

Raised in the Orthodox movement, Sztokman no longer identifies with the denomination. She briefly enrolled in rabbinical school at the Reform-affiliated Hebrew Union College, but is no longer in the program; she now runs a new organization called the Jewish Feminist Academy. A Brooklyn native, Sztokman spoke to JTA about her new book from her home in Modiin, Israel.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

JTA: You have been thinking and writing about abuse in Jewish spaces for a while. Tell me about your journey to decide to write a book entirely focused on abusive rabbis.

Sztokman: I didn’t plan to write a book about rabbis abusing. I really just wanted to dig a little deeper into what was really going on in the community. When the Barry Freundel story happened [a Modern Orthodox rabbi in Washington, D.C., Freundel was convicted in 2014 for secretly videotaping people in his synagogue’s mikvah and ultimately reached a $14.24 million settlement with his victims], that really struck a nerve with me and with a lot of people, because it was so many violations of a space that was meant to be sacred.

I went to a conference for Jewish leadership about a year before the scandal broke, where he was the featured speaker. It was all about issues around conversion, and he was featured as the macher. He promoted himself as controlling the entire discourse between the American and Israeli rabbinate around who gets to be a true convert. And then a year later it comes out that he was controlling all this because he liked access to converts, in order to be able to watch them naked. He had this whole system, telling them where they should stand and how they should stand, all for his personal arousal. This person had all this access and all this authority, with this roomful of people hanging on his every word.

It really illustrates how, when a rabbi is abusive, the abuse takes place in a location where a person’s religious and spiritual life is meant to be sacred. That’s really what pushed me to start talking to people. My book proposal, I wrote in 2015. That’s how long I’ve been working on this.

Were you surprised by how many rabbis have been accused of abuse, across every denomination and every conceivable Jewish space?

It was quite shocking. I shouldn’t say “surprised,” because the truth is that anyone paying attention to the news sees these stories all the time.

These are people we’re supposed to be able to trust, we give them our hearts, we give them our spirits, we give them our Jewish identity, and this is happening. In many cases, it’s very destructive to the relationship between Jews. Even though many people have rebuilt their relationships to Judaism, it doesn’t mean that they can recover. It takes a process. If the person who’s the gatekeeper for your Jewish spiritual practices is this narcissistic abuser, then that has impact.

You offer a character study of an abusive rabbi, or an abusive Jewish spiritual leader. How do you define this personality type, and why are they able to operate in those spaces?

The biggest takeaway was about charisma. We define leadership very closely to charisma. And we know that charisma is one of the signs of a narcissistic personality. Charisma is basically a person who can walk into a room and manipulate people. And the Jewish community tends to give a lot of awards to that person, to that personality.

That’s not to say that every rabbi is a narcissist; I’m not making that claim. But I am saying that there is overlap between the qualities that tend to be culturally valued in rabbis and some of the qualities that define narcissism.

The other point that came up very strongly is about pastoral care as an opportunity for preying, for targeting victims, and also the use of Jewish lingo to have an “in” with their targets. A whole bunch of abuse stories had rabbis talking about “teshuva” [forgiveness] and about “bashert” [soulmates]. A lot of abusers will find the spiritual openings that they’re looking for.

We need to be aware of this, and we need to start thinking about ways to handle the qualities that we want in leadership, versus the qualities that we tend to be starstruck about.

Are these simply narcissistic personality types who are just finding the ways to exploit the system they’re in, and that system happens to be Judaism? Or is there something about our current organizational Judaism that actually encourages this kind of behavior?

I’m reluctant to make that second point, even though it could be concluded from the research. My point is that a lot of people try to say, “Oh, Orthodox culture encourages abuse, because there are so many messed-up things about sexuality.” Or on the other hand, “Oh, look at Reform, it’s so permissive, look at how the girls are dressed,” that kind of stuff. Everybody’s always looking for the cultural hook, to say, “That’s what happens in that culture.” But “that” happens everywhere, and nobody’s immune. Abusers know how to manipulate whatever tools they have at their disposal, and they know how to be these chameleons that are able to use language that they know will speak to their targets.

Your book explores rabbis who commit both child sexual abuse and also adult relationship or power differential abuse, and you often talk about them interchangeably. Is it important to distinguish between these, or do you think they’re all under the same category of abuse?

I think they’re on a spectrum, for sure. I think that there are a lot of efforts to distinguish them from both sides: You see a lot of child sexual abuse advocates saying, “I don’t want to deal with the women’s issues. I deal with children.” I’ve also had experiences with feminist groups who are like, “Yeah, we deal with feminist stuff, we don’t deal with child sexual abuse.”

Both of those attitudes strike me as misdirected, because these are very, very similar dynamics. It all has to do with control and it has to do with emotional manipulation. Who the target is may change from one abuser to another, but it doesn’t matter. It’s still damaging, and it’s still dynamics that we need to be recognizing and observing. These distinctions are, I think, not helpful. They’re not two different phenomena. It just comes down to the particular case of a particular abuser.

Just recently, Rabbi Shlomo Mund was arrested and charged with sexual abuse of minors in Montreal, dating back to 1997. The former day school principal Malka Leifer’s trial for child sexual abuse in Melbourne is scheduled for later this summer. Both cases involve charges more than a decade old, where the accused perpetrator was protected to some degree by their communal leadership, and evaded arrest for years by moving to Israel. What lessons can we draw here?

One is structural and one is cultural. Structurally, yes, communal structures protect abusers by placing them in another shul or another school or whatever. For all kinds of reasons. Because abusers often are people with power, so power protects power. It’s really hard to push back against, because you’re pushing back against networks of power.

The other level is cultural: whose lives are valued and which people do we see as worthy, which people we think of as deserving of our support. Someone who comes forward is seen as someone who’s a nobody, so we can dismiss them as a disgruntled employee. If they move to a new congregation, nobody’s crying. If the rabbi leaves, wow, that will be so damaging. But who cares about the victims? It’s a cultural dysfunction around whose lives are considered valuable.

How can, or should, Jewish institutions change their approach to thinking about rabbis in order to counter this kind of abuse?

We need to disconnect concepts of leadership from performance, versus actual kindness and empathy. Too often as a community we overemphasize performative things like charisma. But this is not a salient definition of leadership, or of the kind of person we should want to put on a pedestal. So culturally we need to change our definitions. Rabbinical schools should rethink some of the ways rabbis are trained, and hiring committees should also be rethinking what kinds of qualities we’re looking for.

Policy-wise, organizations should be more self-aware about who is being supported, how abusers are being supported, and how victims are treated.