Long Island synagogue cancels Ben-Gvir talk amid wide tensions over whether to host him

For a brief period, a large Modern Orthodox synagogue on Long Island was one of the only New York-area Jewish institutions planning to host far-right Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir during his stateside visit this week.

But that quickly changed Thursday, as Young Israel of Woodmere announced that Ben-Gvir’s appearance as a Shabbat guest speaker had been canceled.

“Please note that this Shabbos guest speaker, Itamar Ben-Gvir, has been cancelled,” the synagogue announced in a communication its executive director shared with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Ben-Gvir had been scheduled to address the congregation after sundown on Saturday. The synagogue did not immediately respond to a JTA follow-up for comment on the cancellation, but Ben-Gvir’s office later said the event had been canceled because the intended moderator had suffered a death in his family.

It was at least the second cancellation announcement of an event for Ben-Gvir during the Israeli national security minister’s first official visit to the United States. A synagogue in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn said last week that Ben-Gvir, who had been scheduled to appear at a fundraiser for Chabad of Hebron in the West Bank, would no longer appear.

Others still appear to be on, including at a different Orthodox congregation in Woodmere. The Irving Place Minyan announced a planned event with Ben-Gvir on the afternoon of Shabbat. The flyer for the event promises a question-and-answer session for attendees to “hear about his life, and what inspired him to get involved in Israeli politics.” Requests for comment to the Irving Place Minyan clergy were not immediately returned.

Ben-Gvir’s New York appearances have so far largely been limited to events organized by Shabtai, a Jewish society based near Yale University, where he spoke on Wednesday night. Shabtai also organized an event with Ben-Gvir in Manhattan on Thursday afternoon and intends to host a third in Washington, D.C., this week. Several liberal Jewish groups called for boycotting Ben-Gvir, and protesters dogged both the New Haven and Manhattan events.

Whether Ben-Gvir has other appearances planned remains unclear. Information about his events have circulated largely on WhatsApp.

Right-wing Orthodox communities like Young Israel of Woodmere would have been the most likely destinations for Ben-Gvir. A nationwide network of synagogues that embrace religious Zionism, Young Israel tends to attract a more politically conservative community than other Modern Orthodox spaces, which themselves tend to be more conservative than their non-Orthodox counterparts. (A new poll Thursday showed that 71% of Orthodox American Jews approve of President Donald Trump, who has outlined a vision for the Middle East overlapping in some ways with Ben-Gvir’s.)

But the invitation to Ben-Gvir — who until recently was shunned by even Israel’s right-wing politicians because he had hung a picture of Baruch Goldstein, who massacred 29 Muslims at prayer in Hebron in 1994, in his home — appears to have been a bridge too far for some. According to a reporter for the right-wing Israeli newspaper Israel Hayom, several Orthodox synagogues approached by Ben-Gvir’s people had declined to host him.

After Young Israel of Woodmere announced its event, Robby Berman, a tour guide in Israel who grew up going to the synagogue, called on congregants to boycott and exhorted his followers to call in protest. In the comments section of his Facebook post, his call drew fierce debate.

“Hosting him is also honoring him, and suggesting his religious extremism is acceptable within our community, maybe even representative of it,” wrote one commenter who sided with Berman.

But others argued with him. “It’s very sad that on Yom Hashoa you are suggesting that Jews ban other Jews. Stopping being so divisive!!!” wrote one commenter.

Several hours after his post, with criticism of the synagogue mounting, the cancellation notice went out.

Of several other Young Israel synagogues in the New York area reached by JTA, at least one indicated its members would likely have some contact with him, while another offered a critique of Ben-Gvir’s views.

“He is a Jew so why not enjoy some good food with him,” Howard J. Stern, president of Young Israel Talmud Torah of Flatbush, wrote in an email. The synagogue is located across the street from Essen, a Brooklyn deli where an informal gathering with Ben-Gvir — over cholent — is scheduled for late Thursday evening.

He followed up with a message sharing a different Facebook post, from Rabbi Elie Mischel, a lead educator for an Israel-based organization that connects Christians with Orthodox Jews. Mischel excoriated Young Israel of Woodmere for cancelling its Ben-Gvir event, calling the move “a shameful moment for the diaspora.”

“Remember the Shoah and remembering 10/7 we need to toughen up and be prepared,” Stern added by way of agreement.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for Young Israel of the West Side, in Manhattan, told JTA the synagogue would “respectfully decline” to host Ben-Gvir if asked — but added it had not been.

“Not so much for his politics but rather the fact that he goes against Halacha by going to the Temple Mount and inciting non-Jews around the world,” Jacob Eisenstein, the synagogue’s president, wrote in an email — noting he spoke for himself and not the rabbi.

JTA requests for comment to other New York-area Young Israel branches, including the National Council of Young Israel, the overseeing body, were for the most part not immediately returned Thursday.

Ben-Gvir began his trip in Florida, where he met with several Jewish leaders and institutions including the heads of the Boca Raton Synagogue, the Boca Jewish Center, and the Aleph Institute, an Orthodox aid organization for Jewish prisoners, in addition to speaking at the Jewish Academy in Fort Lauderdale.

He also spoke to a handful of influential Republicans at Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s resort home. While Trump was not present, Rep. Tom Emmer, the House’s majority whip, was in attendance.

“It was my honor and privilege to meet with leaders of the Republican party at the Trump’s Mar-A-Lago estate,” Ben-Gvir tweeted afterwards. “They expressed support for my very clear position on what needs to be done in Gaza, and that it is necessary to bomb the food and aid depots in order to put military and diplomatic pressure to safely return our hostages home.”

Rep. Lloyd Smucker, Republican of Pennsylvania, was also present for the speech, according to Ben-Gvir’s office.

A family memoir is about the search for a Jewish homeland, from Zion to Texas

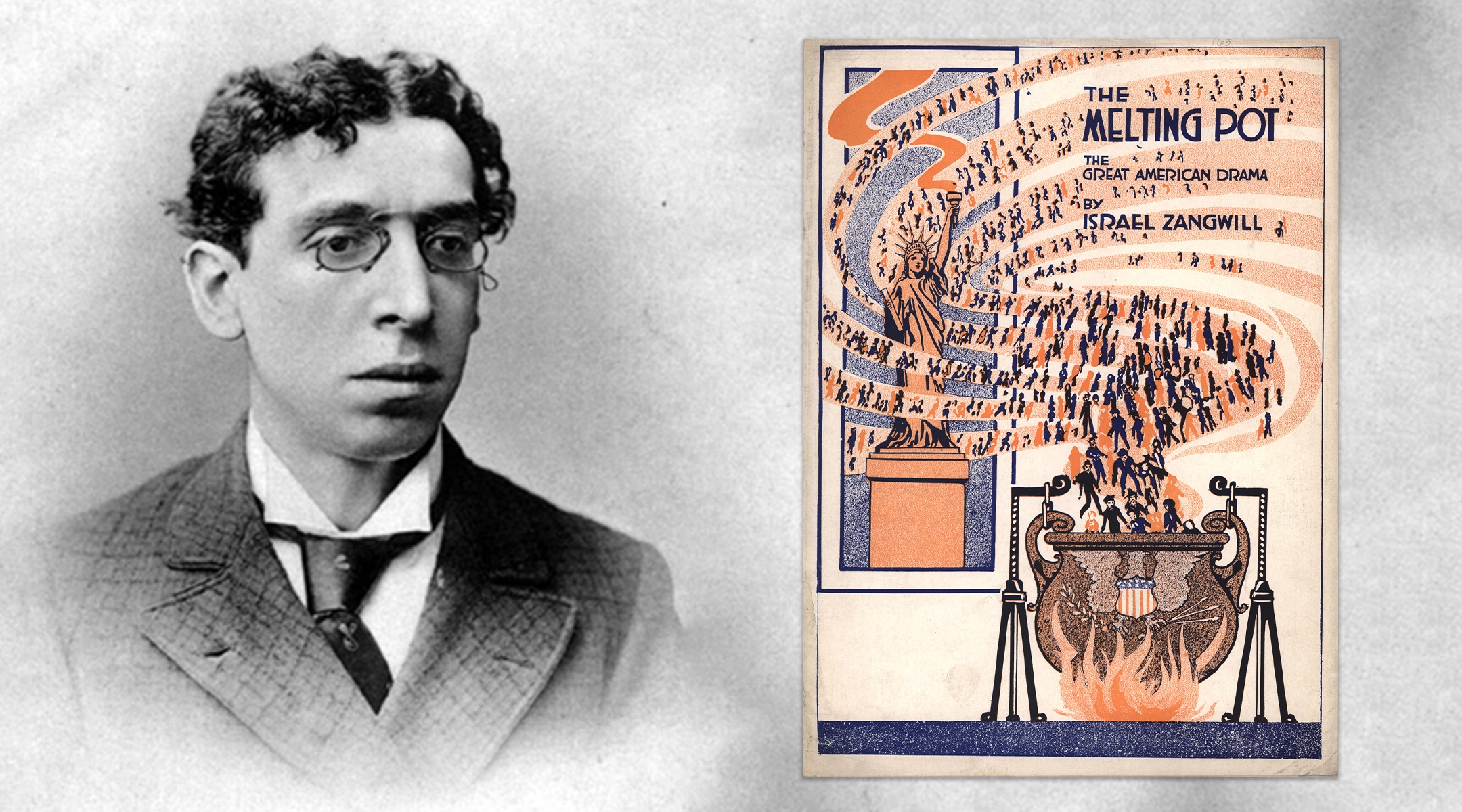

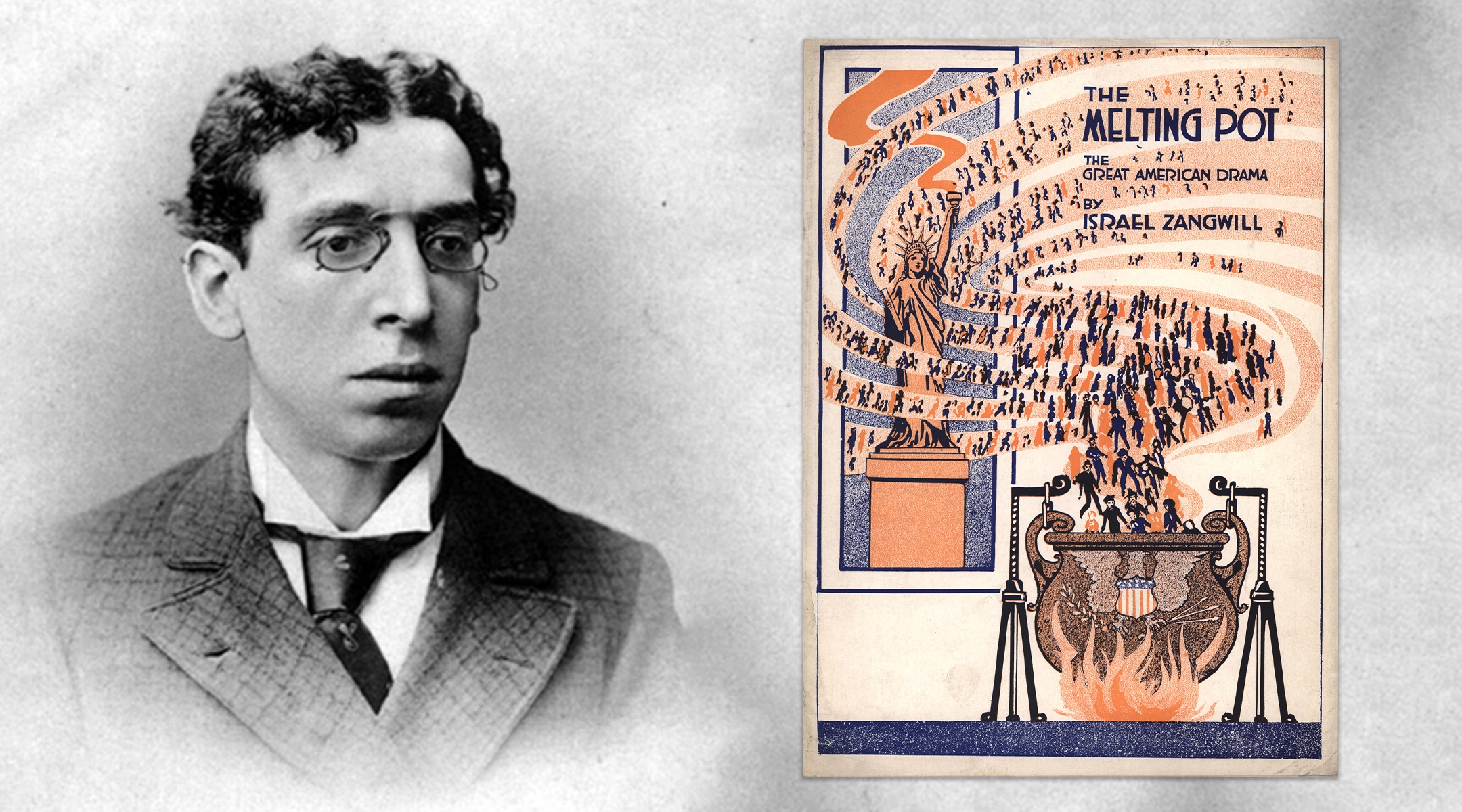

Growing up in London, almost everything Rachel Cockerell knew about the British Jewish writer Israel Zangwill could be summed up in three words: “The Melting Pot.”

The title of Zangwill’s 1908 play, about the romance between a Jewish immigrant and Christian woman he meets in New York, became a metaphor for the way ethnic groups are meant to lose their distinctiveness on the way to becoming fully American.

She was also dimly aware that Zangwill had crossed paths with her great-grandfather, David Jochelman, a Jewish communal leader who died in 1941. As she began research on a family memoir, Cockerell came to realize how significant their bond was — not only as family lore, but as part of a little-known chapter in Jewish, Zionist and even Texas history.

That bond is one of the main threads in Cockerell’s new book, “Melting Point: Family, Memory, and the Search for a Promised Land.” The book tells the story of Jochelman and his descendants — with walk-on parts for the Zionist leaders Theodor Herzl and Zeev Jabotinsky, the financier Otto Kahn and President Theodore Roosevelt, among many others. Their stories become a microcosm of the many different journeys taken by Jews in the 20th century, and the ongoing debate about whether Jewishness can survive in the “melting pot” of the diaspora, or only in a Jewish state.

Jochelman helped Zangwill organize the Galveston Movement, an effort — financed by the Jewish tycoon Jacob Schiff — to divert the flood of Jewish immigrants from Ellis Island to the Texas Gulf Coast. Between 1907 and 1914, when the program was shut down, some 10,000 Jews arrived through Galveston, eventually settling throughout Texas and the American West.

Before Galveston, Zangwill had put his enormously successful writing career on pause to join up with Herzl and the other political Zionists, but split when they refused to accept the idea, offered by Great Britain, of a Jewish state in Uganda instead of Palestine. Alarmed by the pogroms in Eastern Europe, Zangwill founded the Jewish Territorial Organization, known as the ITO, which tried to find a land without people for a people without a land. With the Palestine option seeming distant at best, the ITO saw Galveston as the next best thing. Jochelman, from Kiev, was the ITO’s agent on the ground in Russia.

“A Jewish homeland in Palestine was only one of several possibilities,” Cockerell writes in an introduction. “[A]s one character in the book says, ‘It’s never inevitable at the time.’”

Members of the Jewish Territorial Organization meet on June 1, 1905. Israel Zangwill sits at center, arms crossed, next to the woman in white. David Jochelman is the third sitter to Zangwill’s left, with his arms crossed. A photo of Theodor Herzl is at the rear. (Hashomer Hatzair Archives, Wikipedia)

Galveston is just one of the possibilities embodied in Cockerell’s family story. In New York City, her great-grandfather’s son by his first marriage writes experimental plays under the name Emjo Basshe. And in London, Jochelman’s daughters Fanny and Sonia share a rambunctious house at 22 Mapesbury Road with their husbands and their combined seven children. Fanny’s husband is a “reserved” Englishman, Cockerell’s grandfather Hugh; Sonia husband, Yehuda “Lova” Benari, was a personal assistant to Jabotinsky who moved his wife and children to Israel in 1951.

Cockerell tells the unusual story in an unusual way, by collaging excerpts from primary documents. The historical characters speak in their own words, culled from letters and published work. Contemporary newspaper accounts augment their stories, with all the acerbity and casual prejudices of their day. (The New York Herald describes the notoriously homely Zangwill as “the very archetype of his race – shrewd, witty, wise; spare of form and bent of shoulder, and with a face that suggests nothing so much as one of those sculptured gargoyles in a mediaeval cathedral.”)

Cockerell, 30, has a master’s degree in journalism. Her research for “Melting Point” took her to archives in Texas, Ohio, New York, London, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. “Melting Point” is her first book.

Earlier this week we talked via Zoom about family secrets, the serendipity of Jewish survival and writing about Jews and Zionism after Oct. 7.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

I want to start with how you tell this story: Why did you keep your own voice out of the body of the book and build the story with actualities and primary documents?

My first draft was very conventionally written, and then I read [the experimental novel] “Lincoln in the Bardo” by George Saunders, and I wondered if I could make a Russian-Jewish version of “Lincoln in the Bardo” about Jews going to Texas. I thought that the moments when the primary sources seem to interact with each other, even though [their authors] had been dead for 100 or more years, created a spark of energy that I really loved.

Tell me about your upbringing and what you knew of these stories before you started realizing you had this bigger story to tell.

I knew almost nothing of my dad’s side of the family. There was this huge, dusty portrait of my great-grandfather hanging in my family home in North London, and in this painting, he’s receding into the shadows. He looked like someone very much stuck in the 20th century. I never thought to ask a single question about him until maybe 2018 or 2019 when I wondered if there was anything more to him than what my family was saying, which was that he was a businessman who lost all his money after the Wall Street crash.

He was a Zionist activist, right?

Certain members of my family say he was at the First Zionist Congress, which I never found any proof for. But he was definitely at the second and third and fourth, and he saw Herzl speak, and he was at Herzl’s funeral. And then he was one of those who sort of abandoned the Zionist movement in this quite dramatic split [over the Uganda question]. He would almost have been the leader of the Jewish Territorial Organization, but he was too unknown, and he urged Zangwill to become the leader instead. But none of this was talked about.

Tell me about your Jewish identity growing up.

Almost none. My dad grew up celebrating Passover, but that’s not something that he continued. We always had gefilte fish balls in the fridge, and a jar of borscht in the cupboard. And that was it. I never celebrated Hanukkah, and didn’t speak a word of Hebrew or Yiddish or Russian. My grandmother’s mother tongue was Russian, but she wanted her children to assimilate and to become English. As a result, this heritage that I feel could have been mine did not become mine. Writing this book made me feel more of a sense of everything I lost, everything that fell away down the generations.

Let’s take those generations one by one. Your great-grandfather was a Zionist and later what we might call a “territorialist,” desperate to find a refuge for Eastern Europe’s persecuted Jews, even if it was in Texas. But his son by his first marriage, Emjo (short for Emmanuel Jochelson) Basshe, takes a different route. He moves from Russia to New York City and, like so many Jews of his era, is deeply involved in the theater and the arts, at one point becoming a principal in the New American Theatre, bankrolled by the Jewish financier Otto Kahn. Why was it important to tell his story?

I wanted the reader to be immersed in the melting pot of New York of the ’20s and ’30s, for them to see what it was actually like living in the melting pot. Emjo Basshe was born in the Russian Empire, moved to America when he was a child, and married this Southern belle from North Carolina and had a daughter, also named Emjo Basshe, or Jo, who is now in her 90s.

Jochelman’s daughters by his second marriage, your grandmother Fanny and her sister Sonia, meanwhile, shared a house in London with their husbands and children.

Like many other North London houses in the mid-20th century, it was this pocket of Russian Judaism, which hadn’t really melted into the melting pot, and didn’t until years later. The adults all spoke Russian, apart from my grandfather, Grandpa Hugh, who was this slightly buttoned up, reserved Englishman who was apparently a bit out of place in this mad, chaotic house.

Sonia is married to Yehuda Benari, a personal assistant to the Revisionist Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky. They move to Israel, and this branch of the family is going to keep a different version of the Jewish future alive.

Benari hero worships Jabotinsky, and in the late ’30s, he was going on these tours of Europe, urging European Jews to get out while they could, anywhere: to Palestine, or to America, to England or to somewhere else. In later years, he said the guilt that he felt that he wasn’t able to persuade the European Jews to leave Europe was something he never got over.

British Jewish playwright Israel Zangwill’s “The Melting Pot,” which opened in Washington, D.C. on Oct. 5, 1908, popularized a metaphor for how immigrants were expected to assimilate into American society. (University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections Department)

Were you always aware of your Israeli cousins?

I wasn’t. I think in 2018 or 2019 my dad’s cousin Mimi had an 80th birthday party at 22 Mapesbury Road, and her sister Judy and all Judy’s descendants came over from Tel Aviv. I think that was the first time that I became dimly aware that I had this whole branch of my family who had left London in the early 1950s and moved to Israel, never to return.

I feel your book is about, among other things, the different ways Jews seek to preserve and sometimes discard their identities. One, do you agree with me? And two, at what point did you come to an understanding that this would be what your family memoir would be about?

Yes, that’s in the title of the book, “Melting Point.” It was only about a year in that I realized that this is the story of assimilation and of melting into the melting pot for Jewish immigrants. But I think it’s also a universal experience of leaving a place and arriving in a new place, and part of your identity changing or dissolving away. My family definitely melted into the melting pot of London. You know, I think of myself as British, as a Londoner, more than I think of myself as Jewish or Russian or Russian Jewish. As I was writing the book, I was feeling a certain ambivalence about the melting pot and about assimilation and whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing. The jury’s still out.

I don’t know if he’s being prescriptive or descriptive, but Zangwill is pessimistic that Jews can retain their distinctiveness and what we might call continuity in the melting pot. His wife, Edith Ayrton, wasn’t Jewish. Is it odd that he would push so hard for Jewish resettlement in the American West?

He was quite paradoxical in terms of his ideas about American Judaism. He would say things like, “America is the euthanasia of the Jews. If I had my way, not a single Russian Jew would enter America.” But then he would also proclaim Galveston as the new Jewish homeland, and that the great American West was where the Jewish future lay. He would say one thing in public and another thing in private in a way that entranced me, and which seemed to reflect all my feelings about Judaism and immigration and the melting pot.

Do you know where your great-grandfather would come down on that question: Did Judaism have a future outside of a Jewish homeland?

I think he really believed in the Galveston project, and that America was at least a temporary Jewish refuge. Maybe he didn’t realize that it would become a permanent Jewish refuge, or a permanent Jewish homeland for most of the Galveston immigrants.

You also write that if not for Zangwill, you would not be you.

Just as the Galveston Movement was crumbling, my great-grandfather went on a trip to England and fell ill while he was there. He had been planning on moving to America. When I was researching, I found a letter in the American Jewish Archives from Jacob Schiff to Zangwill saying, “You know, Dr. Jochelman has just told me of his plans to move to America.” [Jochelman] accidentally found himself in England in 1914 and Zangwill wrote to him, “You must stay here. Your future belongs to England.” And so that’s why I’m British, just because of this piece of advice.

The first part of your book goes deeply into the debate among Jews and the British about establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine. You include accounts of the Kishinev massacre of 1903, which puts into context the fears and real danger that were motivating Jews to find a safe haven. Zionism wasn’t just people in top hats dreaming up a Jewish colony in Palestine, but a solution to a dire problem. But I have to ask: Your book comes out at a very fraught time when any subject that touches on Israel leads to a fierce and even ugly debate, and Jewish authors and books are accused of taking sides even if they don’t intend to. Has that been on your mind as you promote the book?

The book is told through primary sources, and it doesn’t really have an agenda. It doesn’t have a bias, and I hope that it, if anything, it just destabilizes the reader in their position about these things, because I felt quite destabilized while reading it. It’s so tempting to draw neat conclusions about things and to have unwavering principles about things. I hope that this book makes readers, if not change their mind, then just question things a little more.

At the 100-year mark, Hebrew University’s American friends are looking to capitalize on a unique moment

In 1974, Pamela Nadler Emmerich — then a teenager from Montreal — arrived in Jerusalem for her freshman year at Hebrew University.

Not knowing what to expect, she signed up for a course on Jewish intellectualism, “Philosophical Implications of Rabbinic Thought,” taught by Montreal native Rabbi David Hartman.

“After class, I went up and told the professor that I had grown up in an Orthodox Jewish community but wasn’t sure if I believed in God,” she recalled. “I didn’t even know what the word belief really meant. And he smiled and said, ‘That’s wonderful, it means you’re thinking!’”

That encounter made a lasting impression on Emmerich, who is now president of the American Friends of the Hebrew University (AFHU).

This month the American organization, which was created to support Hebrew University, is marking its 100th anniversary in tandem with that of the university in Jerusalem. With global antisemitism on the rise and many US campuses a hotbed of anti-Israel ferment, supporting the Hebrew University is more important than ever, according to Emmerich.

“One hundred years ago, the university was founded to be a safe haven for Jewish students. And it still serves that role today,” she said.

Hebrew University was co-founded by Albert Einstein and Chaim Weizmann in 1918 and formally inaugurated on April 1, 1925. Meanwhile, AFHU was founded by American philanthropist Felix M. Warburg, who established a $500,000 endowment for the organization.

Today, fundraising by AFHU, which has an $800 million endowment and raises $65-$75 million annually for the university, accounts for over half of Hebrew University’s overall fundraising revenue.

The historic connections between Jerusalem and New York run deep. Hebrew University’s first chancellor and president was Judah L. Magnes, a prominent New York rabbi. The American Jewish Physicians Committee, founded in 1921, helped finance the Institutes of Microbiology and Chemistry in Jerusalem — which later became part of Hebrew University Hadassah Medical School.

Today, Hebrew University boasts 1,000 faculty members and 23,000 students spread across three campuses in Jerusalem — Givat Ram, Mount Scopus and Ein Kerem — and one each in Rehovot, Rishon LeZion and Eilat.

In 2024, AFHU, which has 45 staffers and regional offices in Florida, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco and Washington, D.C, raised $74.2 million for the university — the biggest annual haul in its history. The organization’s long-term goal is to raise $100 million a year, said Clive Kabatznik, chairman of AFHU’s board.

“The pre-state generation of donors and supporters is essentially dying out. Anybody who was alive when the state was born is at least 77 years old now,” Kabatznik said. “That generation of donors — on whose shoulders we stand — had a different perspective towards Israel and Hebrew University than the high-tech, hedge-fund, private equity players of today.”

The connections between the United States and Jerusalem run deep, with American Friends of the Hebrew University accounting for over half of the university’s total fundraising revenue. (Igor Farberov)

The South African-born Kabatznik enrolled at Hebrew University in 1974, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees, met his wife and got married.

“It was the most incredible liberal arts education one could get,” said Kabatznik, now a venture capitalist who divides his time between Israel and South Florida. “The level of teaching was just through the roof, and it really was a formative experience for me. It molded me and taught me how to think on my feet.”

Since 2003, Kabatznik has been active in AFHU, developing its US-based alumni initiative and spearheading programs showcasing Israeli-led technologies in fields such as cybersecurity, clean energy, fintech and nanoscience.

One of Hebrew University’s most urgent challenges these days is the international boycott of Israeli academics and institutions.

“The major impact Oct. 7 has had is this overt and covert closing of international academic ties,” Kabatznik said. “We’re successful in fighting this on a formal basis, but informally, when professors stop replying to emails, it’s much more insidious.”

In an effort to attract more international students, Hebrew University’s Rothberg International School recently began offering a three-year, fully accredited undergraduate program entirely in English.

Compared to American universities, Hebrew University represents a bargain — and not just on tuition. Philanthropists will find that endowing a chair at Hebrew University costs less than half what it would at an Ivy League school, according to Stanley Bogen, a longtime AFHU donor who is now its honorary chairman and president.

“Whenever I talk to people, I tell them that the money they give goes so much farther in Israel,” Bogen said.

With many Jewish alumni disaffected from their US alma maters’ recent record on antisemitism, Emmerich would like AFHU to get them to become supporters of Hebrew University.

Joshua Rednik, the CEO of AFHU since 2021, said his goal this year is to raise at least 100 new commitments of at least $100,000.

“Over the last 100 years, few institutions have had as significant an impact on the land, people and politics of Israel as Hebrew University,” Rednik said. “We frequently say Hebrew University was the original Zionist project before Israel was even Israel. It has touched every corner of Israeli society.”

Trump mandates universities to report foreign funding, a demand of pro-Israel groups

President Donald Trump has demanded that U.S. colleges and universities report all foreign funding in an executive order issued Wednesday.

The order requires colleges and universities to report all gifts and funds from foreign countries and states that funds could be revoked from schools that fail to comply with reporting standards. It is the latest salvo in a broad set of White House efforts cracking down on campuses — including freezing billions of dollars of funding and arresting student activists.

The executive order comes amid calls from Jewish and pro-Israel groups for greater reporting standards, driven by concerns of foreign anti-Israel influence on campus and in classrooms from countries such as Qatar or Iran. Last month, the House advanced a bill that sought to lower the threshold for reporting gifts from most foreign countries from $250,000 to $50,000.

The House bill received support from AIPAC and the Republican Jewish Coalition. Opponents, including umbrella groups for colleges and universities, say the legislation will inappropriately expand government monitoring of higher education and could hinder international collaboration.

Trump’s executive order cited a Senate committee investigation into foreign funding that described the flow of gifts to U.S. schools as a “black hole.”

“Undisclosed foreign funding raises serious concerns about potential foreign influence, national security risks, and compromised academic integrity,” the order read.

Trump administration texts Barnard professors, asking if they are Jewish

Professors at Barnard College received identical texts from the federal government Monday with a link to a survey asking if they were Jewish.

The text messages, first reported by The Intercept, were sent to the majority of Barnard professors and are part of a review of the school conducted by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, or EEOC, over alleged discrimination against Jewish faculty.

The Microsoft Office form asked current and former employees of Barnard whether they identified as Jewish, Israeli, had Jewish/Israeli ancestry or “practice Judaism.”

It also asked them to indicate whether they had experienced harassment by allowing them to tick a sequence of 10 boxes that included phrases like “unwelcome comments, jokes or discussions” and “antisemitic or anti-Israeli protests, gatherings or demonstrations that made you feel threatened, harassed or were otherwise disruptive to your working environment,” according to The New York Times.

Professors said they were jarred by the federal government asking if they are Jewish, and objected to Barnard giving the government their contact information without notifying them first.

“The federal government reaching out to our personal cellphones to identify who is Jewish is incredibly sinister,” Debbie Becher, a Jewish associate professor of sociology at Barnard, told The Intercept. “They are clearly targeting what most of the United States, I hope and I think, defines as freedom of speech, but only in the case of anti-Israeli speech.”

History professor Nara Milanich, who has researched the experiences of Jews in fascist Italy, told the Times, “We’ve seen this movie before, and it ends with yellow stars.”

Serena Longley, Barnard’s general counsel, told faculty in an email Wednesday that Barnard had shared their contact information with the commission. She wrote that faculty would be given advance notice of any future requirements to share staff information unless a court order prohibited the school from doing so. She added that Barnard had been “robustly defending the college,” according to the Times.

Barnard is a women’s college affiliated with Columbia University in New York, and both have faced escalating scrutiny over pro-Palestinian protests on their campuses, which reached a peak last spring and have continued since.

The Trump administration has frozen $400 million in federal grants to Columbia over its handling of the protests, and has targeted students for deportation. In response, the school has made a litany of changes demanded by the White House, and in February, Barnard expelled two students who disrupted an Israeli history course by banging on drums, shouting “Free Palestine” and distributing fliers with a boot stomping on a Star of David.

Global antisemitism has declined since peaking in the months after Oct. 7, study says

Rates of antisemitic incidents have experienced a “sharp decline” across the world more than a year after Oct. 7, 2023, according to the author of a new study from Tel Aviv University.

The study of global antisemitism, published this week, noted that the number of incidents decreased in many countries in 2024, including France, Britain, Germany, Mexico and South Africa, although rates broadly remain higher than they were before Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel and the outbreak of the war in Gaza.

“Contrary to popular belief, the report’s findings indicate that the wave of antisemitism did not steadily intensify due to the war in Gaza and the humanitarian disaster there,” said Uriya Shavit, the report’s chief editor, in a press release. “The peak was in October-December 2023, and a year later, a sharp decline in the number of incidents was noted almost everywhere.”

The study was conducted by Tel Aviv University’s Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry and the Irwin Cotler Institute for Democracy, Human Rights and Justice. It collected tallies of antisemitic incidents in 2024 from “dozens of police departments, specialized agencies and organizations that monitor and combat antisemitism, Jewish communities, Jewish leaders, and media organizations,” which often employ differing standards and definitions of antisemitism.

Despite the overall downward trend, in some countries, including Australia and Italy, there was a notable spike in the number of antisemitic incidents, the report said. In Australia last year, according to the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, there were 1,713 antisemitic incidents, compared to 1,200 in 2023. Italy saw 877 antisemitic incidents in 2024, compared to 454 in 2023, according to a Jewish watchdog group.

The report was published the same week as another study of antisemitism in the United States by the Anti-Defamation League that reported 9,354 antisemitic incidents across the country, marking a 5% increase from the previous year.

The ADL found that the spike in the United States was partially attributable to an 84% spike in campus antisemitism after a year that saw widespread pro-Palestinian protests at universities. More than half of the total incidents counted were related to Israel or Zionism.

The Tel Aviv University report also discussed hate crime enforcement by local police departments and found that in Chicago in 2023, 10% of antisemitic incidents resulted in arrests. In Toronto, 6% of anti-Jewish hate crimes in 2023 resulted in arrest, and London had an arrest rate of 4% over the same period. In New York City between 2021 and 2023, about a third of antisemitic incidents resulted in arrests.

Authorities raid Michigan homes in probe of pro-Palestinian vandalism of Jewish homes and institutions

This story was updated on April 24, 2025, at 4:12 p.m. EST.

Federal and state agents in Michigan raided at least three different home addresses connected to pro-Palestinian protesters Wednesday, part of what authorities said was an ongoing investigation into more than a year of the group targeting homes and businesses including prominent Jewish locations.

The raids — at homes in Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti and Canton — were not tied to immigration issues or on-campus demonstrations against Israel that have taken place over the last year and a half, according to a spokesman for Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel.

“These search warrants were not investigative of protest activity on the campus of the University of Michigan nor the Diag encampment,” the spokesman, Danny Wimmer, said in a statement, referring to the location of Michigan’s pro-Palestinian student encampment last year. “Today’s search warrants are in furtherance of our investigation into multijurisdictional acts of vandalism.”

The raids — during which some people were detained but not arrested — follow acts of vandalism at the homes of members of the University of Michigan’s Board of Regents, whom pro-Palestinian activists want to cut university ties with Israel.

Late Thursday, Nessel’s office provided a list of the vandalism incidents the raids were investigating. The incidents included one in December, when a group of protesters threw rocks through the window of Jordan Acker, a Jewish regent, while he and his children were home in the heavily Jewish Detroit suburb of Huntington Woods, and left pro-Palestinian graffiti on his car. Another incident from June 2024 targeted Acker’s law office.

A scene of pro-Palestinian vandalism and graffiti at the headquarters of the Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Detroit in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, Oct. 7, 2024. (Government photo)

Another incident, on the one-year anniversary of the Oct. 7 attacks, targeted the Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Detroit in Bloomfield Hills with graffiti reading “Intifada” and “F**k Israel.” Non-Jewish regents at the university, and the university president, have also been targeted by protesters in their own homes. Other graffiti, targeting a predominantly Jewish country club, made explicit references to Friends of the Israel Defense Forces, which had hosted an event at the space the day before. The oldest incidents dated back to February 2024; the most recent occurred in March of this year.

A viral video showed officers breaking down the door of a home. Nessel’s office, on Thursday, said officers broke down the door “following more than an hour of police efforts to negotiate entry to satisfy the court-authorized search warrant.”

Pro-Palestinian activists at the university have been engaged in extreme tactics in an effort to pressure its leadership to divest from Israel.

Acker declined to comment on the raids Wednesday. He previously called the targeting of his own home “terrorism” and “Klan-like.”

The involvement of federal agents in investigating local vandalism is unusual. An attorney representing several University of Michigan protesters told the Detroit Free Press that she believed the raids showed that Nessel’s office was collaborating with the Trump administration, which has cracked down on pro-Palestinian protesters and schools where they have been active and dispatched federal immigration authorities to arrest non-citizen student activists.

“Everyone who was raided has taken part in protest and has some relationship to the University of Michigan,” said the attorney, Liz Jacob of the Sugar Law Center in Detroit. “We are totally convinced that, but for their viewpoints, these students would not have been targeted.”

On Instagram, a pro-Palestinian collective at the university said they were being targeted by “zionist state AG Dana Nessel,” who they accused of working with Trump to “repress pro-Palestinian speech.” (Nessel is Jewish.) Online, other pro-Palestinian groups attempted to link the raids with the high-profile seizings of activists Mahmoud Khalil and Rumeysa Ozturk on other campuses.

The University of Michigan, which has large Jewish and Arab American student populations, has taken more aggressive action against protesters since President Donald Trump’s reelection. In February, it suspended a leading pro-Palestinian student group for two years, in part over its demonstration at a regent’s home.

The school also announced last month, amid pressure from the Trump administration, that it would do away with its flagship Diversity, Equity and Inclusion program. The school had previously fired a senior DEI staffer who allegedly made antisemitic comments at a conference.

72% of American Jews disapprove of Donald Trump’s performance so far, poll finds

Nearly three quarters of American Jews disapprove of the job Donald Trump is doing as president and most dislike how he is handling antisemitism in the United States, according to a new survey.

But American Jews are less disapproving of Trump’s handling of antisemitism than they are of his overall performance, according to the survey, published Thursday by the nonpartisan Jewish Electorate Institute.

The survey was conducted by the Mellman Group, led by Jewish Democratic pollster Mark Mellman, in mid-April and included 800 registered Jewish voters.

“American Jewish voters are deeply distressed about the direction in which Donald Trump is taking the country and oppose many of his key policies,” Mellman, who also founded the advocacy group Democratic Majority for Israel, said in a statement.

The survey found that 72% of American Jews disapprove of Trump’s job performance, including 67% who strongly disapprove, while 24% approve of the job he is doing, including 16% who strongly approve. Some 5% weren’t sure. The poll had a margin of error of 3.5%. The results roughly map to what is known about how American Jews voted in November’s election.

Trump scored poorly among Conservative, Reform and unaffiliated Jews. But among the one in 10 respondents who was Orthodox, he fared far better: More than 71% approve of the job he is doing while fewer than 20% disapprove.

Trump has taken a number of controversial actions — including freezing billions of dollars in funds to universities, arresting non-citizen student activists and revoking student visas — in the name of fighting antisemitism. The survey did not ask about those specific actions, but it did ask whether American Jews approve of how he is handling antisemitism.

Most — 56% — do not approve, while 31% do approve of how Trump is handling antisemitism. The remainder aren’t sure. A large majority of Orthodox respondents approved of his efforts to fight antisemitism, while a plurality of Conservative respondents disapproved. A majority of Reform and unaffiliated respondents also disapproved.

The survey also found that 33% of respondents aged 18 to 29, a demographic encompassing most college students and recent graduates, approved of Trump’s actions on antisemitism, while 52% disapproved.

In addition, 71% oppose Trump’s orders allowing the government to deport people without a court hearing, while 23% approve. Large majorities also opposed other Trump domestic policies, such as his broad tariff regime, cuts to the federal government and actions to penalize law firms. More than 60% of Orthodox respondents approved of the deportations but were more split on other domestic policies.

The survey did not ask about whether American Jews approve of how Trump is handling U.S.-Israel relations or the Israel-Hamas war, a conflict in which Trump helped broker a two-month ceasefire, then repeatedly proposed a U.S. takeover of Gaza and the mass removal of its inhabitants. The survey also didn’t ask whether American Jews approve of his decision to open negotiations with Iran, a move that runs counter to Israel’s preferences.

NIH bans grants for schools that boycott Israeli companies

A new policy from the National Institutes of Health bars colleges and universities from receiving funding if they boycott business relations with Israel.

The policy, which was announced Monday, added to terms and conditions for schools that receive funding from the NIH, which awards tens of billions of dollars in research funding via nearly 50,000 grants.

It also bars eligible schools from operating any diversity, equity, inclusion or accessibility programs if they want to receive funds, part of a broader anti-DEI offensive across the Trump administration.

The policy stated that a discriminatory boycott included, “refusing to deal, cutting commercial relations, or otherwise limiting commercial relations specifically with Israeli companies or with companies doing business in or with Israel or authorized by, licensed by, or organized under the laws of Israel to do business.”

While pro-Palestinian student groups have long advocated boycotts of Israel, including at last year’s wave of campus encampments, those efforts have not found success. Administrations have almost universally rebuffed them or voted them down. Last year, the president of California State University was placed on leave after announcing an academic boycott of Israel.

The new policy is effective immediately and will apply to all NIH grants. If schools are found to institute Israel boycotts or DEI programs, they could be asked to pay back the funds.

“NIH reserves the right to terminate financial assistance awards and recover all funds if recipients, during the term of this award, operate any program in violation of Federal anti-discriminatory laws or engage in a prohibited boycott,” the policy read.

The new rules align with a January executive order by. President Donald Trump that dubbed DEI programs “illegal,” and has spurred efforts to dismantle federal DEI initiatives across the country. And it adds on to laws in dozens of states that prohibit state institutions, including public universities, from engaging with entities that boycott Israel.

The anti-DEI push has ensnared Jewish-focused materials in some instances. At the Pentagon, Holocaust remembrance web pages were removed and a display honoring Jewish female naval academy graduates was taken down, ostensibly to comply with the order. A number of Jewish groups have also protested the anti-DEI policies.

The new NIH policy is the latest restriction placed on U.S. campuses, which have faced intense scrutiny from the Trump administration over their responses to antisemitism. Many universities including Columbia, Harvard, Brown, Northwestern and Cornell have already faced steep cuts to federal funding. In addition, a growing number of student pro-Palestinian activists have been arrested and threatened with deportation, or had their visas canceled.

An elite Jewish society at Yale fractures over its director’s embrace of Itamar Ben-Gvir

Fissures are opening in a Jewish society at Yale University known for its commitment to open discourse after its director announced plans to host the far-right Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir.

At least three members of the selective society have resigned over director Rabbi Shmully Hecht’s decision to host Ben-Gvir, whose record includes extremist rhetoric and convictions for crimes including providing support to a terror organization.

Until recently, politicians on Israel’s right avoided partnering with Ben-Gvir because he had hung a picture of Baruch Goldstein, who massacred 29 Muslims at prayer in Hebron in 1994, in his home. Now, he is national security minister — and most American Jewish groups are eschewing him on his first official visit to the United States. Another group that was hosting him, facing backlash, said it canceled the event.

But Hecht told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency last week that he had a different take. “I admire Ben Gvir,” Hecht told JTA in an email last week. “Itamar promotes what he believes is best for his people that democratically elected him.”

Several Shabtai members objected to Hecht’s comments, in which he praised both Ben-Gvir as a “bold, resolute leader” and the extremist Rabbi Meir Kahane, whom Ben-Gvir admires.

“Shabtai was founded as a space for fearless, pluralistic Jewish discourse,” two of the members who resigned, both Jewish Yale alums, wrote in an email to a Shabtai listserv viewed by JTA. “But this event jeopardizes Shabtai’s reputation and very future.”

One of the letter’s authors, David Vincent Kimel, said in an interview that he used to admire Shabtai and Hecht — until the Ben-Gvir invite.

“I’m deeply concerned that we’re increasingly treating extreme rhetoric as just another viewpoint, rather than recognizing it as a distortion of constructive discourse. When the loudest voices are those at the extremes, they overshadow the nuanced, moderate perspectives that often hold the key to genuine understanding and compromise,” he said. “Just like people calling for the dismantling of Israel, the killing of Jews on Oct. 7, are also a grotesque extreme.”

Their pushback, which comes in addition to public protests by both other Jewish Yale graduates and current Yale students, reflects tensions behind the scenes at Shabtai, established in the 1990s as a Jewish intellectual salon. The dissent reflects division among elites over the limits of acceptable speech on Israel — and how the current political moment is testing long-time relationships, including within Shabtai.

The society has no formal affiliation with Yale. Still, Ben-Gvir’s visit has prompted a response from within the broader Yale community. More than 200 people on Tuesday announced their intent to form an encampment to protest Ben-Gvir. The attempt was disbanded hours later, after Yale’s “Free Expression Facilitator” announced the students were in violation of protest rules and risked disciplinary action and arrest.

“This is only the beginning,” a coalition of Yale pro-Palestinian groups who promoted the encampment announced on Instagram the morning after being disbanded. “Intifada until victory!”

Netanel Crispe, a Hasidic student and activist at Yale University, confronts pro-Palestinian protesters attempting to start a new encampment at the university in New Haven, Connecticut, April 22, 2025. The protesters were organizing against Jewish off-campus Yale society Shabtai’s invitation to far-right Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir to speak near campus. (Screenshot via X/Courtesy of Netanel Crispe)

Now, a rally is planned for outside the venue where Ben-Gvir is set to appear. “When murderers are invited, the people must show up,” a flyer for the protest shared on Instagram reads. “Our people are slaughtered. Our children buried. Yet war criminals are given a stage.”

Jewish and Israeli students who oppose Ben-Gvir are also planning a protest. And earlier on Wednesday, a group of 20 rabbis who themselves are Yale alums published an open letter through T’ruah, a liberal rabbinic group, urging Shabtai to disinvite Ben-Gvir. “We believe strongly in free speech, but free speech does not mean that everyone has to be invited to speak,” the letter reads.

The critique cuts at the historic heart of Shabtai, founded in 1996 as a Jewish alternative to the so-called “secret societies” of the Ivy League, like Skull and Bones, where membership is exclusive, opaque and lifelong. Its core activity is salon-style events in which a broad range of ideas are elevated and debated.

Located in a historic mansion near Yale’s New Haven campus, Shabtai was founded with the name Eliezer by Hecht, who previously founded Yale’s Chabad-Lubavitch house, along with now-Sen. Cory Booker and Jewish academics Ben Karp, Michael Alexander and Noah Feldman — a liberal constitutional scholar and the author, last year, of “To Be a Jew Today.” Requests for comment to the other co-founders were not returned.

Since its founding, a small number of students in their final year of school at Yale — both Jews and non-Jews — are admitted as members every year, and remain members for life. Unlike other societies of its ilk, Shabtai opens its doors to invited guests and at times the public for its events, which members are required to attend and which take place twice a week, including on Shabbat.

The society went by several different names until it was renamed Shabtai in 2014, following a donation of more than $1 million from Israeli businessman Benny Shabtai that also funded the purchase of the mansion. (A few years later the group’s namesake sued the organization and Hecht, claiming his gift had been misallocated; that suit was later withdrawn.)

Over kosher dinners, Shabtai guests listen to lectures and engage in debates with notable visiting guests, many of whom expound on Jewish topics. Shabtai’s student members play a large role in organizing and introducing the talks. Phones are put aside for the duration of the events, which can last for several hours; in recent years they have also been recorded and posted to YouTube.

It’s all part of what Hecht, who selects many of the guests himself and who often steers or freely interjects in the discussions, has described as his vision for “a place to engage with people you disagree with.” Hecht has cultivated strong relationships on both sides of the political aisle: in addition to Booker, former GOP presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy — who floated ending U.S. aid to Israel during his campaign — was also a Shabtai member and has called Hecht a mentor.

Even Shabtai members who disagree with Hecht’s politics praise both him and his wife Toby, who helps run the center; the two have created “a second home to so many of us,” the two alums wrote in their resignation letter.

Historically, Shabtai’s guests have run the ideological gamut. In addition to Booker, a New Jersey Democrat who returned to the center in 2022, other recent guests have included Jodi Rudoren, until recently the Forward’s editor-in-chief; Suzanne Nossel, head of literary free-speech group PEN America; and William Schabas, a former United Nations investigator who led an investigation into possible war crimes committed by Israel during the 2014 Gaza war. The society has even hosted anti-Zionists on occasion, including Philip Weiss, the Jewish creator of the anti-Zionist publication Mondoweiss.

Kimel said his own debate with Schabas a decade ago as a highlight of his time at Yale. “I was impressed that they really did try to bring pluralism to the table,” he said.

But after Oct. 7, Hecht appears to have become publicly less forgiving of Jewish voices on the left — which some of the dissenting members say has led to “inconsistency” with how his free-speech principles are applied.

In November 2023, Hecht circulated a Change.org petition through the Shabtai network that called for “the global excommunication of Jews who endanger the Jewish people.” The petition, which has earned 91 signatures to date and does not itself mention Shabtai, named 10 Jewish figures with a history of criticizing Israel ranging from liberal to far-left.

Among the names Hecht said he holds “responsible for fostering the rise of global antisemitism and endangerment of Jewish lives worldwide”: New York Times columnists Thomas Friedman and Peter Beinart; J Street founder Jeremy Ben Ami; acclaimed playwright and Israel critic Tony Kushner; IfNotNow co-founders Simone Zimmerman, Max Berger and Alissa Romanow; left-wing academics Norman Finkelstein and Noam Chomsky; and Yisroel Dovid Weiss, of the anti-Zionist haredi Orthodox sect Neturei Karta.

These Jews, Hecht maintained, should be barred from “synagogues, schools, community centers, nonprofits, weddings, and bar mitzvahs,” as well as from burial in Jewish cemeteries and entry to the state of Israel. With enough signatures, Hecht promised, “we will request Rabbinical Courts around the world to Halachically enforce this grassroots-excommunication.”

Given Hecht’s support for excommunicating such Jews for their beliefs, the Shabtai alums wrote, his decision to host Ben-Gvir “is not promoting free speech, but rather legitimizing terrorism and state repression.”

“Free speech cannot be selectively applied,” they wrote. “In fact, if Ben Gvir’s invitation is justified by free speech, then that principle must extend to equally extreme voices on the other side, as well as to all Yale student protestors, even those we strongly disagree with. If it doesn’t, this is more about advancing one narrative than free speech.”

Some Jewish leaders have exhorted Jewish groups to boycott Ben-Gvir on his first visit to the United States since becoming Israel’s national security minister in a far-right coalition government with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, an alliance that many non-Orthodox Jewish groups, along with liberal Israelis, have strongly opposed.

Israel’s National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir visits the Temple Mount in Jerusalem’s Old City, April 2, 2025. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

Members of the anti-Netanyahu Israeli protest group UnXeptable demonstrated against Ben-Gvir from the moment he disembarked his plane in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, on Monday. (A spokesperson for the minister’s office said his Florida stops included meetings with Boca Raton and Bal Harbour Jewish community leaders, visits to Israeli-owned businesses including a firearms store, and a speech at the home of former Israeli government official Ori Schwartz.)

“Some ideas are so beyond the pale, so contrary to Jewish values that have sustained our people throughout the millennia, and so at odds with the values on which Israel was founded, that they do not deserve legitimization in the public square,” Rabbi Rick Jacobs, president of the Union for Reform Judaism, wrote in an op-ed this week in the left-leaning Israeli newspaper Haaretz. He urged: “Don’t invite him to your congregation or welcome him to your community. Educate your synagogue and Jewish community on the dangers Ben-Gvir poses.”

Hecht seems to be doubling down on including Ben-Gvir since drawing criticism. In addition to the New Haven event, Hecht also plans to host talks with Ben-Gvir on New York’s Upper East Side on Thursday and in Washington, D.C., later this week. A video of Ben-Gvir landing in New York on Wednesday shows him embracing a smiling Hecht.

In an emailed invitation he sent to Yale faculty on Friday, viewed by JTA, Hecht linked the Ben-Gvir event to the post-Oct. 7 campus climate for Jews.

“In light of the Anti Israel/Anti-Semitic climate of today’s Ivy League campuses, it it vital that we at Yale hear perspectives from unapologetic Israeli leaders committed to securing the Holy land of Israel as the one eternal homeland of the Jewish People, and a refuge for its non-Jewish citizens and minorities that enjoy democracy in a region of tyrants and demagogues,” Hecht wrote. (Ben-Gvir, in contrast to Hecht’s descriptions of his views, has said the rights of Jewish Israelis should be paramount; Rep. Ritchie Torres, a staunchly pro-Israel Democrat, has repeatedly called him a “demagogue.”)

Hecht went on to call Shabtai “a true oasis for free speech at Yale and the world at large,” adding, “At a personal level I believe it is specifically unapologetic events such at [sic] this one that has preserved Yale as a more moderate safe haven for Jews in the current toxic Ivy community of extremism.”

Following his initial comments last week, in which he described Shabtai’s free-speech principles as “Talmudic,” Hecht did not respond to follow-up questions from JTA.

Beyond the alumni rebellion, Jewish students at Yale who had once celebrated Shabtai as a place to engage in thoughtful debate amid a more broadly hostile campus environment are now criticizing it.

One current Jewish Yale student who has himself participated in Shabtai events in the past rebuked the group’s decision to host Ben-Gvir in the student newspaper.

Senior Liam Hamama, who is active in the liberal pro-Israel group J Street, was directly involved in another controversial Shabtai event last year when he attended an event with Simcha Rothman, another far-right Israeli politician, and challenged him directly.

But now, Hamama wrote, a line had been crossed. He compared Ben-Gvir to the white supremacist mass shooter Dylann Roof, Russian dictator Vladimir Putin, and Hamas supporters, saying Shabtai wouldn’t invite any of them to speak, either.

“When we treat someone as an honored guest and wine and dine with them,” Hamama wrote, “we signal that their views are within the realms of that which we deem acceptable and legitimate speech.”

Correction: This story originally misstated the name of the head of PEN America. It has been corrected.