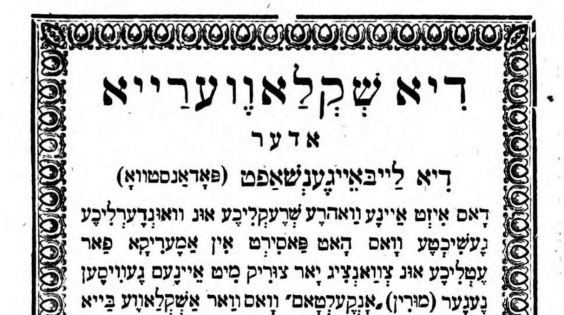

Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Yiddish: sounds crazy, no? But across 19th-century Russia and eastern Europe, Jews eagerly devoured Russian Jewish writer Isaac Meir Dik’s (1807-1893) Yiddish version of the antislavery classic. Dik’s 1868 translation, renamed Slavery or Serfdom, presents an antebellum South like something from an alternate universe: now the slaves (and the masters criticized for being too kind for their own good) are Jewish.

The translation made it to the New World too, where it gained critical and popular attention. As a 1905 review in the respected American Jewish monthly New Era Illustrated Magazine made clear, Dik didn’t just translate the language. He translated the whole tale. Jewish customs and textual references pepper the story. When she learns that her husband plans to escape, Eliza bewails his master’s scorn for their traditional Jewish marriage, since slave marriages weren’t legally recognized. Uncle Tom, a devout Jew, compares himself to the Biblical Joseph, sold into bondage. Jewishness wasn’t just a gimmick to attract readers. It added to the novel’s treatment of slavery.

It’s the ending that makes Slavery or Serfdom one of the best things ever. The former slaves go to Canada where the remaining non-Jews convert to Judaism, all together establish a synagogue with Uncle Tom as president, and live happily ever after.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.