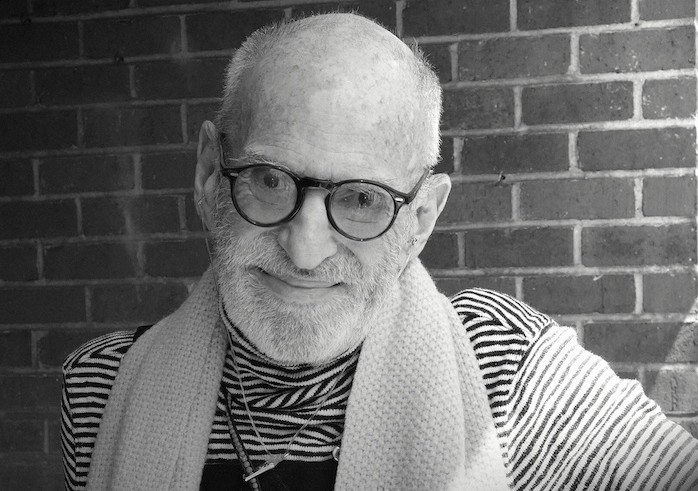

The new documentary “Larry Kramer in Love and Anger” begins, aptly, with Kramer yelling.

Kramer was one of the loudest, angriest, most militant and — the film argues — most effective AIDS activist in the 1980s and ’90s. He called AIDS a “plague” and “genocide.” He berated public officials like Ed Koch and Ronald Reagan for doing nothing and screamed at fellow activists for not doing enough.

He also helped force AIDS onto the national agenda, browbeat the FDA into changing its drug-testing procedures to rush through potential treatments and usher in the drug cocktails that ultimately transformed AIDS from a death sentence into a manageable inconvenience.

He was, depending on your point of view, a biblical prophet, a pain in the ass, a lifesaver, a Cassandra, a hysteric or just a loud-mouthed New York Jew. Most likely, he was a little bit of each.

But as documentarian Jean Carlomusto’s affectionate and informative portrait makes clear, Kramer was more than just an angry screamer (though he was certainly that).

For starters, he was a successful movie producer and screenwriter, then a hit novelist and ultimately a highly successful playwright who used the stage to highlight and dramatize the struggles of the AIDS crisis. His most notable play, “The Normal Heart,” was recently adapted as an Emmy-winning HBO movie, which earned critical praise and returned Kramer to the spotlight once again.

He was also, as the film makes clear, an idealist and even a romantic. Even before AIDS appeared in the early 1980s, Kramer warned gay men their focus on sex was making it impossible to find love.

And he was intensely savvy. Kramer’s brand of confrontational activism — breaking into FDA offices, dumping the ashes of AIDS victims on the White House lawn, staging noisy protests in St. Patrick’s Cathedral during mass — were not expressions of blind rage but theatrical performances, impossible to ignore.

For Kramer, the stakes were high: Before writing “The Normal Heart,” according to Carlomusto, Kramer visited Auschwitz and was deeply moved by it. He was also disturbed at the history that led up to the Holocaust, as years of silence and passivity gave way to horror and death. In Kramer’s view, anything short of the tireless pursuit of justice was complicity in the evil of inhumanity. As he repeatedly reminded the world, “People are dying!”

That sense of urgency pervades the film as well, which debuted at Sundance and will appear on HBO in June to help celebrate Kramer’s 80th birthday. Carlomusto energetically conveys, through Kramer, the desperation and fear of the early AIDS struggle, and her presentation of Kramer is both loving and well-aware of his faults.

Ironically, one of Kramer’s greatest disappointments was a product of his greatest success. Just as his activist group, ACT UP, attained its maximum level of influence in the 1990s, a new class of drugs called protease inhibitors appeared, and the AIDS cocktail was born, sending the death rate plummeting. ACT UP was consumed by internecine squabbles, and the bottom fell out of the protest movement.

For Kramer, the tragedy is that as far as he is concerned, the problem hasn’t gone away. AIDS can be contained but not cured, the drug treatments carry serious side effects, and the disease continues to spread throughout the world. Yet too much of the world no longer shares his sense of urgency. The powerful sense of fear that helped fuel the movement has disappeared.

Larry Kramer still rages, but he is again a lonely prophet, angrily demanding justice.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.