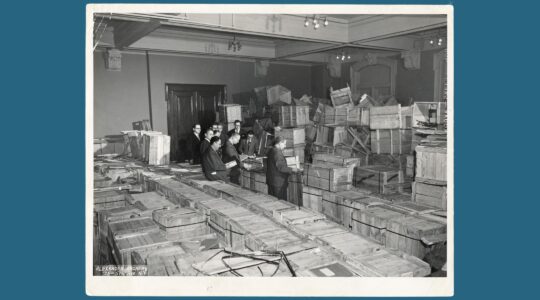

In a scene from the Oscar-nominated documentary “5 Broken Cameras,” co-director Emad Burnat is shown inspecting his cameras. (Alegria Productions)

LOS ANGELES (JTA) — It’s hard to imagine two more divergent perspectives on Israeli-Palestinian relations: that of a Palestinian farmer whose village is resisting the encroachment of a nearby Jewish settlement and of the security service chiefs responsible for maintaining order in the Palestinian territories.

Surprisingly, however, these protagonists in two documentaries vying for an Academy Award in the best documentary feature category come to much the same conclusion: that military force alone will neither solve the conflict nor assure the Jewish state’s survival.

“The Gatekeepers” presents the perspectives of six men who headed Israel’s Shin Bet security agency over the past three decades — tough men who oversaw such operations as the targeted assassinations of Hamas and other terrorist leaders.

In “5 Broken Cameras,” a Palestinian farmer chronicles his village’s resistance to the construction of an Israeli settlement and to the soldiers who try to squelch their protests.

The tone of “5 Broken Cameras” is more emotional and “Gatekeepers” more intellectual, but both show that Israelis will accept a level of criticism too daunting for most Americans to stomach or for mainstream Hollywood to depict. And if that weren’t enough, the Israeli government actually helped pay for the production of both films.

“We Jews are masters of self-criticism,” Dror Moreh, the director of “Gatekeepers,” said in an interview at a Los Angeles hotel. “It’s in our genes.”

The six Shin Bet heads featured in “Gatekeepers” vary as much as the prime ministers who appointed them, but they share a hard-headed intellect and a disdain for most of Israel’s politicians, past and present.

Avraham Shalom, who headed the Shin Bet from 1980 to 1986, is the oldest of the six. He helped track down and kidnap the Nazi Adolf Eichmann, and pursued both the Arab perpetrators of the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre and extremist Jewish West Bank settlers.

Dressed in plaid shirt and red suspenders, the avuncular Shalom sets much of the tone for his successors, who generally agree that despite the rebuffs and failures, Israel must try to negotiate with the Palestinians and take some tentative steps on the path to peace.

“Negotiate with anyone?” Moreh asks somewhat incredulously in the film.

“Yes, anyone,” Shalom answers, even Hamas and Islamic Jihad.

Yaakov Peri, who assumed the post in 1988, was the key figure in battling the second intifada, setting up a vast network of Palestinian informers and collaborators, and allegedly authorizing “exceptional practices” during Shin Bet interrogations. Yet Peri reflects in the film on “the memories etched deep inside you … when you retire, you become a bit of a leftist.”

Moreh said his most surprising moment came when interviewing Yuval Diskin, who served as Shin Bet head from 2005 to 2011. Moreh asked for Diskin’s reaction to a quote by Yeshayahu Leibowitz, a left-wing academic who asserted that Israel’s control over the West Bank would lead to the Jewish state’s inexorable moral corruption.

To Moreh’s astonishment, Diskin nodded in agreement, saying, “Every word is [written] in stone.”

Emad Burnat, the cameraman, narrator and co-director of “5 Broken Cameras,” is a world removed from the well-educated, commanding Shin Bet chiefs of “Gatekeepers.”

A Palestinian farmer, his family has cultivated the land of Bil’in, a village of 1,900 just east of where Israel separates from the West Bank. When his fourth son, Gibreel, is born in 2005, he gets a video camera to record the boy’s infancy and childhood, as well as the surrounding village life.

At about the same time, the religious settlement of Modi’in Illit is established nearby, protected by a fence that bars the village farmers from much of their land and olive groves. The villagers respond with weekly demonstrations. Israeli soldiers are called in to prevent the villagers from marching on the settlement, escalating the confrontation.

A self-taught photographer, Burnat and his camera capture the events, to the annoyance of the soldiers. Although some blood is spilled later on, the initial casualties are the cameras, which are smashed, replaced and smashed again.

Five cameras go down, but the sixth is still doing duty today, Burnat says by phone from Bil’in.

Among the Israeli sympathizers who join the Bi’lin protesters is Guy Davidi, a Tel Aviv filmmaker who befriends Burnat and his family.

Two years ago, Burnat showed Davidi his huge cache of video footage with the idea of fashioning it into a documentary. Davidi signed on as co-director and producer, raising $334,000, including $50,000 from government-funded Israel Film Council.

Though it sounds like an unalloyed success story, the film’s road to Oscar contention became a little bumpy after initial media reports in Israel and the United States trumpeted the unprecedented feat by “two Israeli films.” The claim justifiably angered Burnat, opened him to criticism from his Palestinian compatriots and led to a boycott of the film in Arab countries.

“This is a Palestinian film,” Burnat told JTA. “It’s about my village and mine is the major contribution.”

Under Academy Awards rules, documentaries are not entered by countries (as is the case for foreign-language feature movies) but by individual filmmakers and their distributors. So “5 Broken Cameras” is officially labeled as a Palestinian-Israeli-French co-production.

The film illustrates one other point, too. As in most films by Palestinians, Israeli characters may be depicted as unwelcome interlopers, but they are not made into monsters or Nazis.

“Many of the West Bank Palestinians have worked in Israel as construction workers, gardeners and so forth,” Davidi said. “They speak our language and know more about us than we know about them. Even if they hate us, they understand something about the complexity of our society.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.