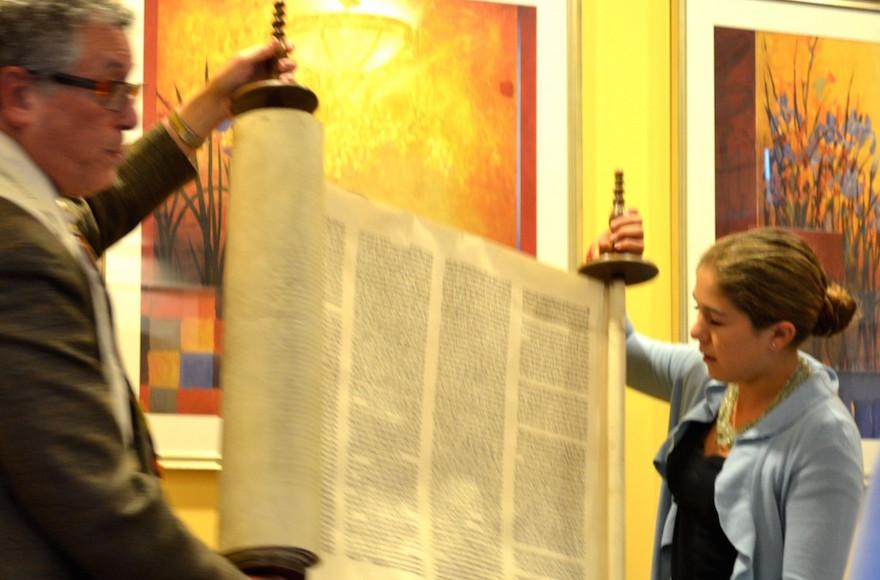

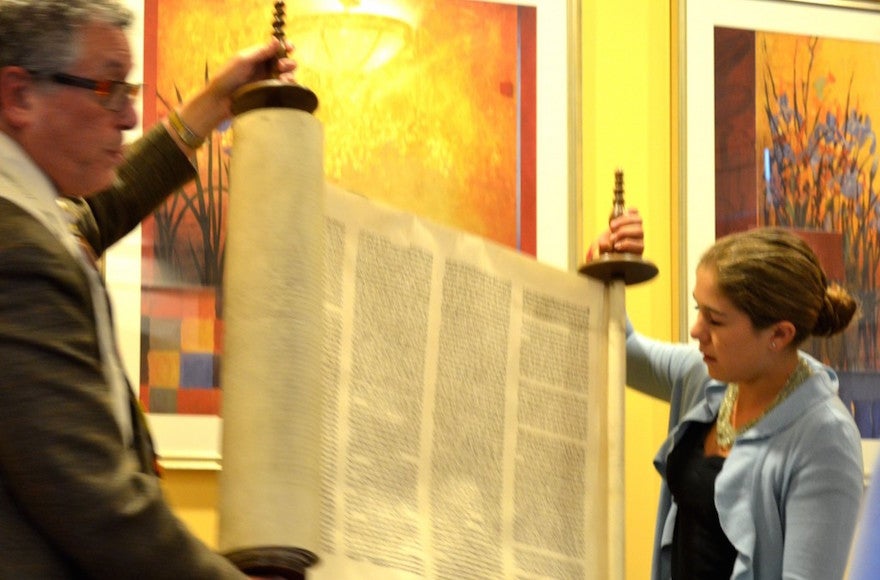

Charlotte Smith and Rabbi Jerry Levy at the dedication of the family Torah scroll rescued by her great-great-grandfather, at AlmaVia, a senior residence community in San Rafael,California, Oct. 2012. (Julie Ann Kodmur)

LOS ANGELES (JTA) — It was the “Night of Broken Glass” in Germany, Kristallnacht — a national pogrom of death and destruction of Jewish property and the rounding up of Jews — and Dietrich (David) Hamburger was in hiding.

Hamburger was the leader of a small congregation that met in his home in Fuerstenau, a countryside village in what now is the province of Niedersachsen. Someone had warned him about the coming onslaught, and on Nov. 9, 1938 he went into hiding in the local Catholic hospital.

“The cover story was that he was in for a hernia,” said Edith Strauss Kodmur, his granddaughter and the family’s historian.

Dietrich (David) Hamburger, who rescued the community Torah of Fuerstenau, Germany, days after Kristallnacht in 1938, is shown in a 1948 photo taken in Winterswijk, the Dutch town in which he hid from the Nazis. ()

This spring — 75 years later and a continent away at a Californian winery — Kodmur’s granddaughter will have her bat mitzvah. And Charlotte Ruth Smith on that day will read from the Torah scroll that her great-great-grandfather rescued soon after that tragic night.

But Hamburger would need to escape Germany and the Torah would need to find its way back to his family.

“By prior arrangement, one of his hired hands met him in the hospital garden while the nuns were at Mass,” Kodmur recalled from detailed notes. “He drove Dietrich back to his home where he packed, taking an oil portrait of wife Rosa [he was a widower] and the community Torah with him.”

Kodmur thought Hamburger had removed the rollers, or etz chaim, to make the Torah easier to transport.

“He then boarded the train to Holland, to Winterswijk, to his daughter Bette,” said Kodmur, whose family as well as her uncle Siegried, Hamburger’s son, had left Germany for the United States in 1938.

Kodmur as a small child had visited her grandfather frequently, she said, recalling that he would sit in the garden with his children on the Sabbath, reading to them and discussing the Bible.

“He was very adventuresome, and well-dressed. Involved with the horse and cattle trade business,” she said.

A memorial book for the Holocaust victims of Winterswijk titled “We Once Knew Them All” uses quotes from the people who lived in the eastern Holland town to tell what happened to Hamburger and his family.

“My parents had a Jewish person in hiding during the last year of the war, a Mister Hamburger. We called him by his alias, ‘Uncle Derk,’ ” a community member recalls in the book. “His daughter, son-in-law and their children died in the concentration camps. He also had a son in America.

“Once we were threatened by a posting of German soldiers at our home. Uncle Derk hid behind a wardrobe. Obviously we noticed that Mr. Hamburger was very afraid of being discovered. My Father told Uncle Derk to act differently, otherwise everyone might be arrested.

“On the morning of liberation, I woke up Uncle Derk. He was so shaken by my excited talk that his false teeth fell out: into the chamber pot!”

From another community member: “Father Hamburger stayed a while in Winterswijk after the war. My, my how that man cried over his grandchildren.”

After the war, while Siegfried was visiting his father in Holland, Hamburger gave him the Torah scroll to bring back to his home in Redwood City, Calif. It stayed there until Siegfried died.

Kodmur, who lives in the San Diego area, knew that Siegfried had given the Torah to his son Steven. But she had lost touch with that part of the family and was uncertain of its whereabouts.

In 1996, Kodmur’s daughter Julie Ann and her fiancee, Stuart Smith, attended a pre-wedding counseling session with Rabbi Jerry Winston in San Anselmo, Calif. The rabbi mentioned that he had officiated at the marriage of Julie Ann’s cousin.

Julie Ann had heard the stories of her great-grandfather’s escape with the Torah and its unknown whereabouts, and in the whirr of Jewish geography and family history that ensued, both Julie Ann and Winston soon realized that Steven Hamburger had given the rescued Torah to the rabbi.

“I didn’t even think to ask him for it,” said Julie Ann, thinking back on that meeting.

In 2000, Winston officiated at the baby naming for her daughter Charlotte, but Julie Ann and the rabbi would lose touch.

It was more than a decade later, when Julie Ann began thinking about her daughter’s bat mitzvah, that her thoughts again turned to the Torah. Beginning a search last year, she soon discovered that Winston had died and the small congregation he led had disbanded. Could he have given the Torah to another synagogue?

She called the big synagogue in the San Francisco Bay Area’s Marin County, Rodef Shalom, and the historic synagogue in San Francisco, Temple Emanu-El, and many others leaving messages. Then she received a call back.

“The woman had a German accent and said she was a friend of Rabbi Winston’s. She told me that his sons had given the Torah away, to Rabbi Alan Levinson of Sausalito,” remembered Julie Ann, who lives with her husband, Stuart, and Charlotte in the small town of St. Helena, Calif., near the family-owned Smith-Madrone Winery.

After contacting Levinson, who had been a longtime friend of Winston’s, they quickly exchanged what each knew of the provenance of the scroll. It was the one. “His plan was to give it to another synagogue,” said Julie Ann.

Meanwhile, Julie Ann also was looking for a rabbi to prepare Charlotte for her bat mitzvah. She connected with Rabbi Jerry Levy, who worked with students via Skype. She had known Levy growing up in San Diego; he had been the rabbi at her brother David’s bar mitzvah.

Levy also was the chaplain at AlmaVia, a faith-based elder care community in San Rafael, Calif., where according to the rabbi, 18 to 20 of the 120 residents are Jewish. Julie Ann inquired if Levinson would consider giving the Torah to Levy for use in his community. Levinson agreed and this month, Levy held a dedication at AlmaVia.

With Levinson, Julie Ann and Charlotte present — she helped roll the scroll to the correct reading — the scroll to be known as the Hamburger/Fuerstenau Torah was dedicated.

“They were kvelling,” said Levy of the AlmaVia residents on hand.

Speaking at the ceremony, Charlotte recounted her great-great-grandfather’s escape on Kristallnacht and the Torah’s travels.

“We found it, and not only would I be able to use it for my bat mitzvah, we could give it a home here at AlmaVia,” she said.

“This coming spring, I will borrow the Torah from all of you here at AlmaVia for my bat mitzvah. And the story will continue.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.