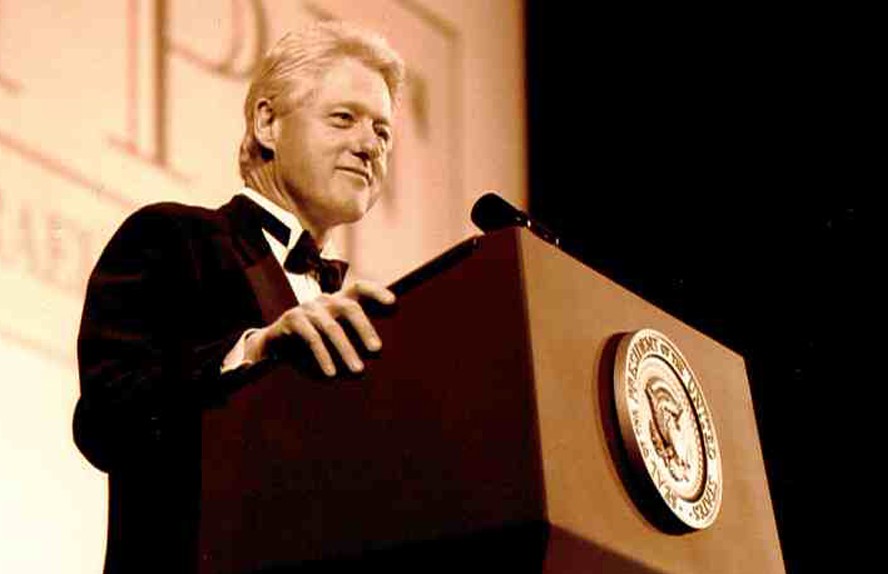

President Bill Clinton speaking at the 2001 Israel Policy Forum dinner, January 2001. (Courtesy IPF)

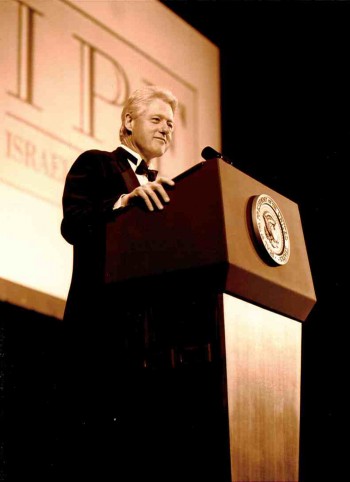

Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert is flanked by Seymour Reich, left, and Marvin Lender at the 2005 Israel Policy Forum annual dinner. (Courtesy IPF)

WASHINGTON (JTA) — When President Bill Clinton chose in January 2001 to unveil his Clinton Parameters for Arab-Israel peacemaking, he chose an Israel Policy Forum gala to do it. Four years later, then-Israeli Deputy Prime Minister Ehud Olmert sought the same audience to announce then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s willingness to negotiate with the Palestinians.

In more recent years, however, the IPF has nearly disappeared in influence and presence. Now it hopes to revive itself with some of Jewish life’s heavy hitters, people who hint they are frustrated with the seemingly partisan politics of J Street and others.

“You could make the case that an organization like IPF is more needed now than ever, promoting a two-state solution without playing politics,” said Aaron David Miller, a former negotiator in the first Bush and Clinton administrations who since his retirement from government in 2001 has been associated with IPF. “You do have increasing polarization in the Jewish community now, and it’s not a good thing.”

Miller is not alone in his assessment.

Among the new significant names signing onto IPF’s revival are Rabbi Eric Yoffie, who just ended his term as president of the Union for Reform Judaism; U.S. Rep. Gary Ackerman (D-N.Y.), who is retiring and in recent years had public disagreements both with the Israeli establishment and J Street; Deborah Lisptadt, the eminent Holocaust historian; and philanthropist Charles Bronfman.

"I believe that the broad base of the American Jewish community wants and needs realism [that] to my mind, neither the left nor the right are providing,” Bronfman said in an email to JTA. “IPF’s work in all areas will attempt to foster the real probabilities of a two-state solution."

Next month, some of the group’s advisers, veteran and recent, will meet in New York with reporters to discuss the revival. An item in the press release asks: “What did happen to the IPF?”

Is there room for a Jewish group that pushes the Israeli consensus on peacemaking and keeps above the cacophony of the American partisan fray?

Twenty years ago it was a no-brainer. The IPF was founded at the behest of then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who was frustrated with the American Israel Public Affairs Committee’s slowness to embrace the nascent Oslo peace process with the Palestinians.

Peter Joseph, IPF’s president now, said he is not alone in seeing the need for nuance in an age when pronounced dissent from some groups characterized debate on the region. Joseph would not be more specific, but he did not deny that this description could apply to J Street, the liberal lobby that bills itself as “the political home for pro-peace, pro-Israel Americans” and which grew by leaps and bounds just as IPF was fading.

A J Street spokeswoman declined to comment on IPF’s resurrection.

But M.J. Rosenberg, IPF’s Washington director until 2009 and now the author of an often biting blog with a pronounced leftist slant, said the Middle East policy community may not be as welcoming as it once was.

“J Street will remain the address for people who want to oppose AIPAC,” he said. “All this will do is drain support away from J Street because it won’t drain support from AIPAC.”

Rosenberg stressed that he wished his former employer the best.

Meanwhile, former AIPAC spokesman Josh Block noted how fraught the waters were for IPF’s reemergence. He noted in a statement that Joseph was funding Open Zion, an ideas exchange hosted by Peter Beinart, who has stirred controversy with his writings suggesting that younger American Jews are growing alienated from Israel. Beinart recently proposed boycotting settlement goods while increasing purchases from Israel proper.

Joseph, who is in the private equity business, told Tablet recently that he found Beinart’s boycott call “polarizing” but confirmed to JTA that he continues to fund Open Zion.

“You can’t be effective if your support and your ideas are fringe,” Block said in an email interview with JTA. “It’s not immediately clear what niche IPF will seek to fill. While he has distanced himself from Peter Beinart’s repulsive call for a boycott against Israel, the president of IPF and its key funder is still underwriting Mr. Beinart’s struggling blog, which provides a platform for anti-Israel, one-state crackpots and people who oppose sanctions to stop Iran’s dangerous nuclear pursuit.”

Yet there was cheering from at least one institutional corner.

“We welcome any effort to advance the two-state solution and to secure Israel as a Jewish state and a democracy, living in peace and security with its neighbors,” said Debra DeLee, the president of Americans for Peace Now. “We will be happy to work hand in hand with a reinvigorated IPF.”

IPF’s rise and fall was synonymous with the peace process itself.

Throughout the 1990s and into the first years of the 21st century, IPF occupied a unique Middle East policy nexus: the making and influencing of policy, and the thinking about it. Among those associated with the group at the time were Sandy Berger, Clinton’s national security adviser; Stephen P. Cohen, a Yale and Princeton Middle East scholar whose citations by newspaper pundits achieved a notorious ubiquity; and Marvin Lender and Alan Solomont, Democratic Party fundraisers with reputations as kingmakers.

Its Israeli associates had roots in the country’s security establishment, lending heft to its emphasis on negotiations and eventually a two-state solution.

Among Clinton’s last acts as president was to outline the “Clinton parameters,” the peace plan deal rejected by the Palestinians. He chose an IPF gala to make his historical speech.

Yet as attitudes hardened during the second intifada, IPF’s emphasis on interaction seemed less relevant. Still, IPF managed to retain some clout. Its assiduous nonpartisan status attracted attention from Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, who would invite then-IPF president Seymour Reich to meetings with Jewish leaders when she sought a voice to balance AIPAC’s hawkish line.

IPF’s last major hurrah was its 2005 gala dinner in New York, when Olmert, representing Sharon, signaled a new readiness to talk with the Palestinians. Olmert, in a speech that made headlines, declared that “We are tired of fighting, we are tired of being courageous, we are tired of winning, we are tired of defeating our enemies."

The ensuing efforts to renew peace talks by President George W. Bush and later President Obama never gathered momentum, and the dialogue in the American Middle East peace community — and among American Jews — grew more fractious. There was a dichotomy between those who favored the classic AIPAC strategy of heeding the Israeli government of the day and those such as J Street who favored intensive U.S. involvement.

IPF was not spared the dissension: Rosenberg argued within the organization for a more assertive alignment with J Street, while Joseph insisted on maintaining the nonpartisan middle.

By late 2009, with J Street a frequent interlocutor with the Obama administration, Rosenberg left, and IPF was absorbed into the pro-Obama think tank, the Center for American Progress. The Washington office closed; all that remained was a small four-person operation in New York.

IPF was little heard from until it parted ways with CAP late last year. Joseph said the parting was amicable.

Joseph is in Israel this week at the Israeli Presidential Conference, networking and seeking Israeli interlocutors in the security and political establishments. One likely partnership is with Blue White Future, the new group convened by top former security officials that advocates a degree of unilateral disengagement from the West Bank.

The IPF president added that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s broad, new national unity government can provide an impetus toward peacemaking with the Palestinians. The key, he said, is not to impose American ideas but to get a sense of the Israeli reality and encourage the trends within it that seek peace.

“We pay very significant attention to Israel’s security needs,” Joseph said. “Anyone looking at this seriously needs to take that into account.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.