SAN FRANCISCO (JTA) — A Conservative rabbi in Georgia is challenging the constitutionality of his state’s kosher law, saying it favors Orthodox religious standards and constitutes state entanglement in religion.

The case follows the overturning of similar kosher laws in two other states and the city of Baltimore. It also comes at a time of growing public interest in kashrut, following last year’s immigration raid at the Agriprocessors meatpacking plant in Postville, Iowa, and the ongoing trials of the plant’s owners and managers.

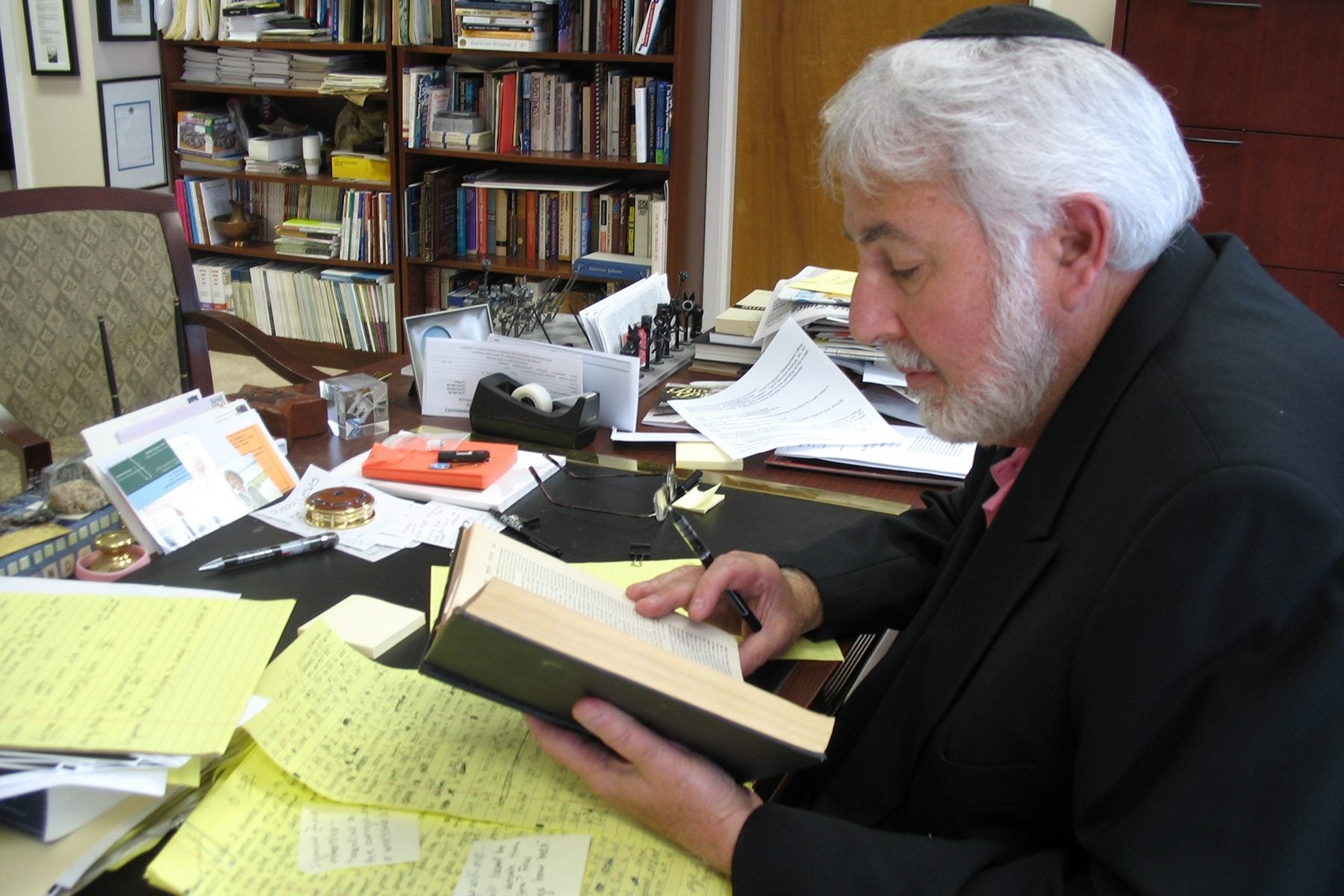

On Aug. 7, Rabbi Shalom Lewis of Congregation Etz Chaim in Marietta filed a lawsuit in Fulton County Superior Court claiming that Georgia’s Kosher Food Labeling Act, passed in 1980, prevents him from fulfilling his duties as a rabbi.

In a complaint filed on Lewis’ behalf, the American Civil Liberties Union charges that Georgia’s kosher law, which defines “kosher food” as “food prepared under and of products sanctioned by the orthodox Hebrew religious rules and requirements,” ignores different kosher standards of other streams of Judaism.

The Georgia law imposes criminal sanctions for violations of the law, including presenting food as kosher if it has not been so determined by Orthodox authorities.

Thus, the lawsuit contends, the law as written violates the free exercise, establishment, equal protection and due process clauses of the U.S. and Georgia constitutions.

The case is the fourth of its kind nationwide. Kosher laws that used similar Orthodox definitions of “kosher food” were overturned in New Jersey in 1992, Baltimore in 1995 and New York in 2003.

Daniel Mach, director of litigation for the ACLU Program on Freedom of Religion and Belief, said the arguments in the Georgia case will refer to those rulings.

Lewis, who in his capacity as a rabbi provides kosher supervision to a restaurant and bakery, and acts as rav hamachshir, or senior kosher supervisor, of kosher events held in his synagogue, said he brought the suit because the kosher law in Georgia criminalizes his actions.

“Technically I’ve been a criminal since 1980, which I’m not thrilled about,” he said.

Lewis noted that no Conservative rabbi, including himself, has been prosecuted under the law, but said “it could happen,” and as a taxpayer he did not want to help fund a law that discriminates in this way.

Rabbi Reuven Stein, director of supervision at the Atlanta Kashruth Commission, said he was “disappointed” to learn of the lawsuit. He said the law was enacted in 1980 to protect kosher consumers from fraud, and unlike the kosher laws struck down in New York and New Jersey, Georgia’s law provides no enforcement mechanism.

“It’s toothless anyway,” Stein said, which is why he was “surprised” anyone would complain about it.

Furthermore, he said, nothing in the law prevents a Conservative rabbi from giving hekhsherim, or kosher certification, in contrast to what Lewis charges in his suit.

“Conservative rabbis do give hekhsherim in the state of Georgia, and we’ve never had an issue with it,” Stein said.

Stein said he receives “at least a call a month” from consumers regarding kosher fraud or mislabeling. If the law were overturned, he said, it’s unlikely a “more politically correct one” would replace it, and consumers would have no protection.

Lewis claimed the owner of a local vegetarian restaurant under Conservative supervision received a complaining call from the Atlanta Kashruth Commission, a charge Stein denied.

Rabbi Julie Schonfeld, executive director of the Rabbinical Association, the professional body of Conservative rabbis, said Lewis’ lawsuit is “part and parcel” of the Conservative rabbinate’s ongoing engagement in kashrut.

Many Conservative rabbis give kosher supervision and certification nationwide, she said, and the movement holds periodic courses to teach Conservative rabbis how to perform this function. The next one is scheduled for May.

“His proactive stance is consistent with the activist stance towards kashrut in our movement,” she said, noting in particular the Conservative movement’s year-old commission on Hekhsher Tzedek, or certificate of social justice, a forthcoming initiative to rate kosher-certified food products according to standards of health, safety and working conditions.

“We very much have an eye on the larger society, how we live as Jews in America,” she said. “Hekhsher Tzedek is a clear example of that, and this case is another very fine one.”

Conservative Judaism holds that the laws of kashrut are binding, and in general follows the same kosher laws as Orthodoxy. The movement differs only in the practical application of certain laws, notably the Orthodox restrictions on non-Jews making cheese and wine and lighting cooking fires, which Conservative authorities do not follow. Conservative authorities also permit certain fishes, such as sturgeon and swordfish, forbidden by the Orthodox.

In July 1992, New Jersey’s Supreme Court overturned state kosher regulations that defined kosher in terms of “orthodox Hebrew religious requirements,” ruling that it violated the constitutional prohibition on the establishment of religion.

New Jersey now operates under a “full disclosure scheme,” whereby manufacturers or purveyors of kosher food must fill out forms indicating what they sell and under whose authority. The forms are filed with the state and posted for public view, so consumers can decide for themselves whether to patronize the establishment.

The disclosure form is careful not to make religious judgments. Purveyors must state, for example, whether they sell pork or shellfish, or mix milk and meat, but they can still call themselves kosher, as long as they don’t conceal these facts.

“You can put down absolutely anything in the world you want,” said Rabbi Yakov Dombroff, who has headed New Jersey’s Bureau of Kosher Enforcement since 1986. “Literally, pork could be kosher. The state has no interest in what you call kosher, as long as you’re in compliance with the disclosure.”

In 1995, the Baltimore City Code’s kosher ordinance was overturned as being in violation of the Establishment Clause after a hot dog vendor was fined for putting non-kosher hot dogs too close to kosher ones on his rotisserie.

Nearly a decade later, in 2004, New York State changed its kosher laws, which also defined kosher as “according to orthodox Hebrew religious requirements,” following a lawsuit brought by butchers in Commack. In their original 1996 case, the butchers claimed state kosher supervisions were engaged in a regular pattern of fining them because their store was supervised by a Conservative rabbi.

The New York State Kosher Law Protection Act of 2004, modeled on New Jersey’s “full disclosure” system, requires producers, distributors and retailers of food sold as kosher in the state to submit information about their products, including the identity of the person or organization that certifies them, to the Department of Agriculture and Markets. The information is published in an online directory.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.