LOS ANGELES (JTA) – A highly charged controversy between two self-described “passionate” advocates – one African-American, one Jewish – ended with pledges of mutual friendship and future cooperation.

The two principals in the brouhaha, following a closed-door, three-hour meeting May 1 with Los Angeles and national leaders of their respective communities by their sides, declared an end to a confrontation that a barrage of e-mails and blogs had quickly escalated from a local incident into a widely reported one.

The initial spark was ignited April 4 when a historically black fraternity honored Daphna Ziman, the Israel-born wife of wealthy real estate investor Richard Ziman and his partner in numerous political and philanthropic causes, for her work with foster children.

The keynote speaker was the Rev. Eric Lee, the president and CEO of the Los Angeles chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the civil rights organization founded by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Ziman asserted that during his talk Lee accused Jews in Hollywood of exploiting black artists and perpetuating black stereotypes in films, and rejected any future collaboration with the Jewish community.

She left the dinner in tears and immediately sent e-mails to some friends and subsequently to the Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. The reaction was more than she expected.

“I just sent out eight e-mails,” Ziman said, “and next morning I had millions of responses.”

While the figures may be exaggerated, it was obvious her charges had struck a nerve in some segments of the Jewish community.

Lee’s declaration strongly denying the statements attributed to him did nothing to slow the spread of the story. It was picked up by the national and international media, pundits and bloggers.

Politics inevitably inflamed the incident and increased its news value: Ziman in her e-mails made allusions to the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, the one-time pastor of Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama, and she has given considerable support to rival candidate U.S. Sen. Hillary Clinton.

Concerned by the growing acrimony, Esther Renzer, the international president of the StandWithUs, a pro-Israel grassroots organization headquartered in Los Angeles, turned to a friend: Rabbi Marc Schneier, a New York-based Orthodox clergyman, as well as the founder and president of the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding, which works to improve black-Jewish relations (and now Muslim-Jewish ties).

Schneier, in turn, contacted Charles Steele Jr. of Atlanta, the national president and CEO of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and both flew to Los Angeles for the hoped-for reconciliation meeting.

Joining them at a roundtable in Ziman’s Beverly Hills home were Ziman, Lee and Renzer, as well as Amanda Susskind, the regional director of the Anti-Defamation League; Rabbi Jacob Pressman, the rabbi emeritus of Temple Beth Am in Los Angeles; and Roz Rothstein, the international director and CEO of StandWithUs.

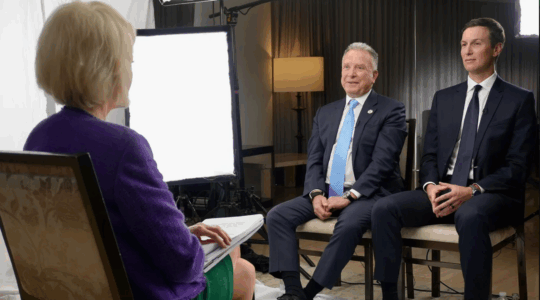

Following their private lunch and discussion, the eight participants spent another two hours talking to three reporters.

Judging by the determinedly upbeat comments of the participants, their private deliberations had touches of a peace summit, a revival meeting and an exploration of past, present and future relations between the African-American and Jewish communities.

Ziman and Lee, sitting side by side and occasionally linking hands, were a picture of amity and good will, with both crediting their reconciliation to “divine intervention.”

Both declined to comment directly on Ziman’s original charges on Lee’s comments or his denial that he had made such remarks.

“We didn’t churn up the past because it no longer matters,” Lee said.

Ziman noted that in the past three weeks she had moved “from shedding tears to a sense of hope,” and she stressed that the meeting’s participants had a responsibility not to damage future generations through prejudice.

“I request the pledge of every religious leader in the United States that no racism be spouted in public places and places of worship,” she said.

Lee described Ziman and himself as “two passionate and well-intentioned people who both love God.”

The participants frequently invoked King’s name and example. They noted, too, that their meeting was taking place on Yom Hashoah, the day for commemorating the Holocaust.

Schneier sought to put the meeting into the larger context of black-Jewish relations over the decades, from the halcyon days of the civil rights struggle, to the acrimony of the early 1990s and the Crown Heights riots in a New York City borough, to a certain healing process in recent years.

“Fifteen years ago I couldn’t have called on the leader of the SCLC to join me because there were no communications between African-Americans and Jews,” he said.

According to Schneier, enlightened black leadership “skipped one generation” between King and the current evolving leadership, with the generation in between including such divisive figures as Louis Farrakhan and Wright.

In pledging their future cooperation, Lee noted that he had invited Ziman to address his congregation, while she mentioned possible cooperative projects between a Jewish day school, such as the Milken Community High School, and a predominantly black inner-city school.

Asked separately whether they regretted any of the words and actions that led to the confrontation, Lee and Ziman responded in different ways.

Lee observed that though he had held Passover seders at his congregation for the past 10 years, “I have learned a lot during the past three weeks, which have been the most difficult of my life.”

Ziman said she had “acted instinctively” when confronted with perceived anti-Semitic slurs but did not regret her subsequent actions.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.