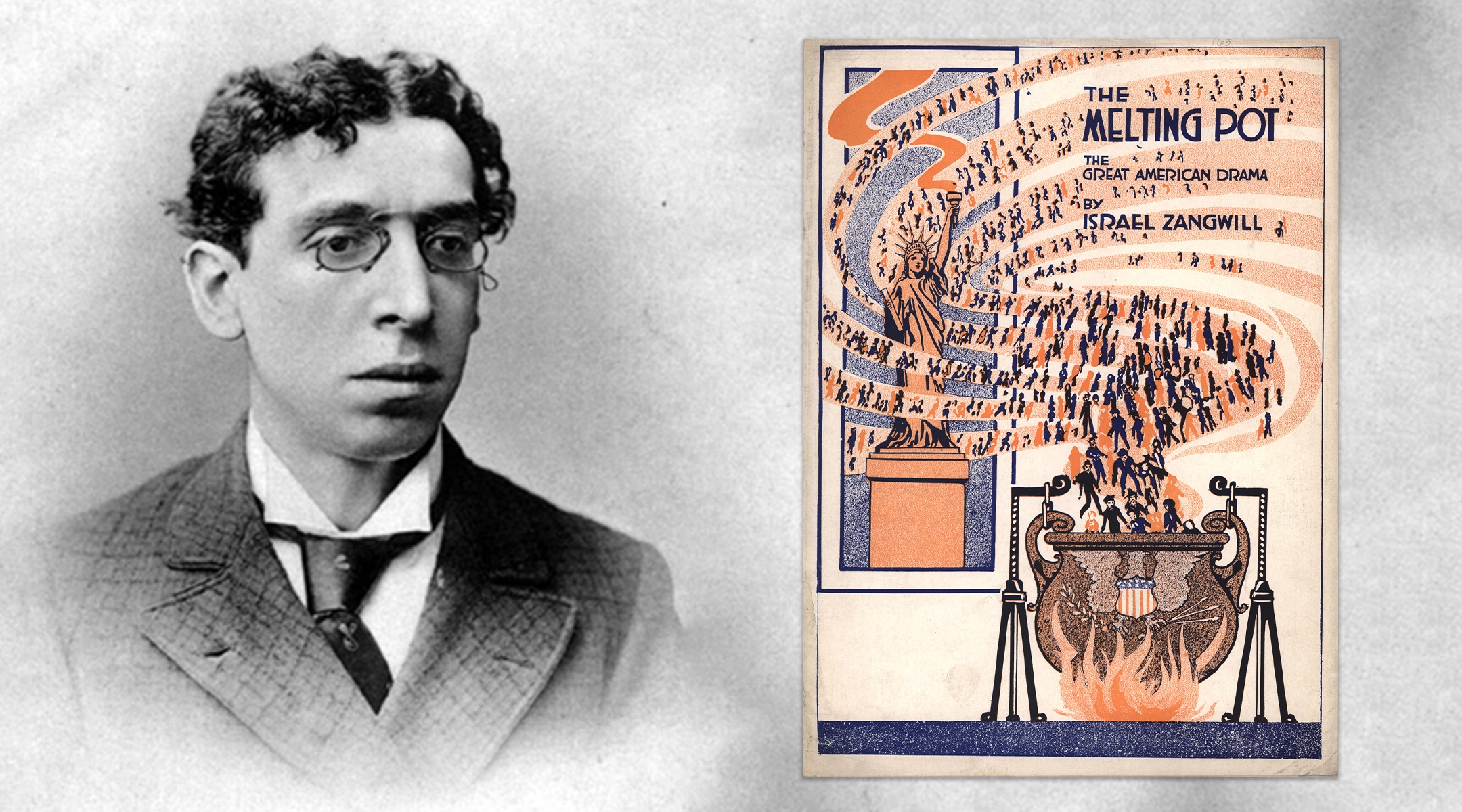

Growing up in London, almost everything Rachel Cockerell knew about the British Jewish writer Israel Zangwill could be summed up in three words: “The Melting Pot.”

The title of Zangwill’s 1908 play, about the romance between a Jewish immigrant and Christian woman he meets in New York, became a metaphor for the way ethnic groups are meant to lose their distinctiveness on the way to becoming fully American.

She was also dimly aware that Zangwill had crossed paths with her great-grandfather, David Jochelman, a Jewish communal leader who died in 1941. As she began research on a family memoir, Cockerell came to realize how significant their bond was — not only as family lore, but as part of a little-known chapter in Jewish, Zionist and even Texas history.

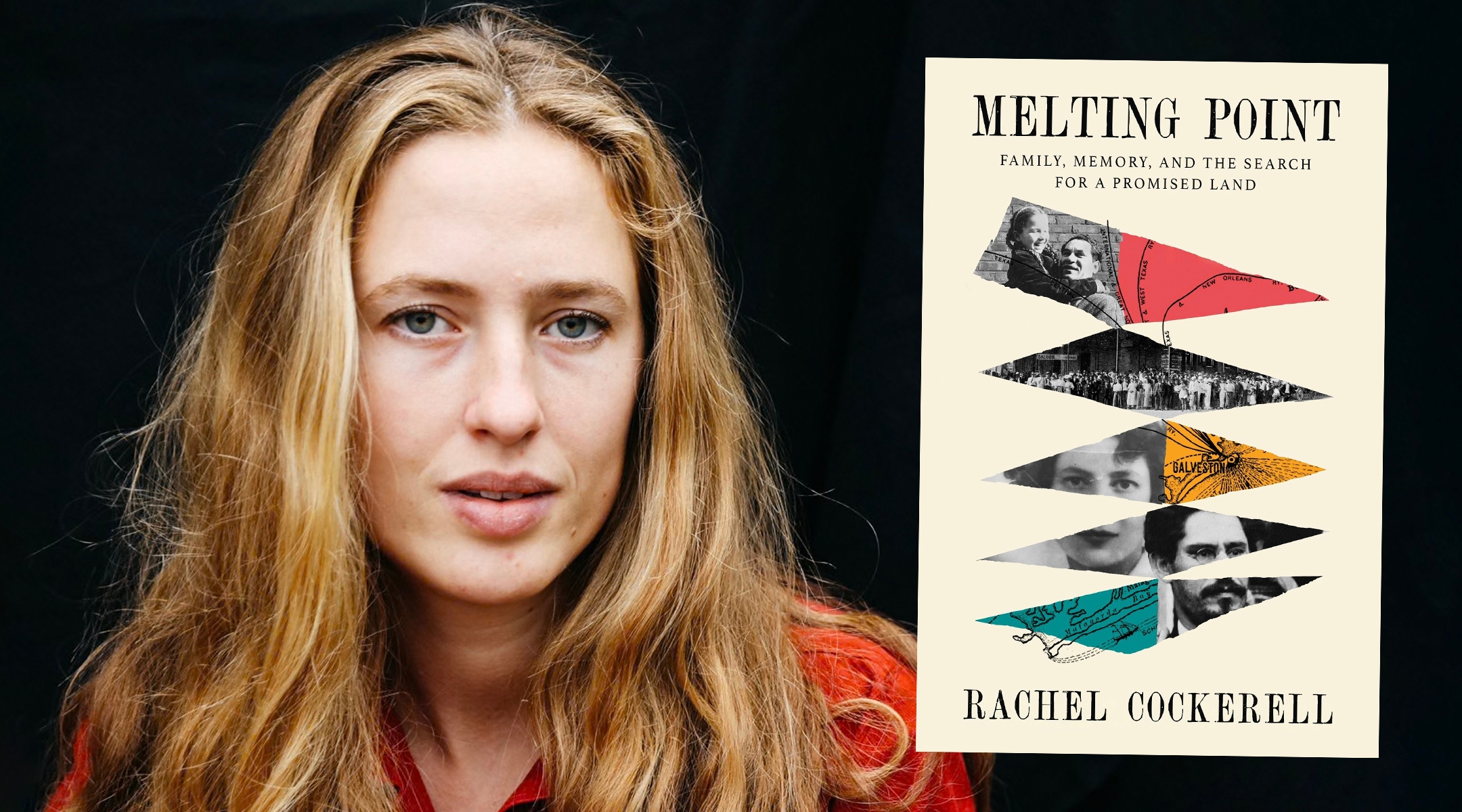

That bond is one of the main threads in Cockerell’s new book, “Melting Point: Family, Memory, and the Search for a Promised Land.” The book tells the story of Jochelman and his descendants — with walk-on parts for the Zionist leaders Theodor Herzl and Zeev Jabotinsky, the financier Otto Kahn and President Theodor Roosevelt, among many others. Their stories become a microcosm of the many different journeys taken by Jews in the 20th century, and the ongoing debate about whether Jewishness can survive in the “melting pot” of the diaspora, or only in a Jewish state.

Jochelman helped Zangwill organize the Galveston Movement, an effort — financed by the Jewish tycoon Jacob Schiff — to divert the flood of Jewish immigrants from Ellis Island to the Texas Gulf Coast. Between 1907 and 1914, when the program was shut down, some 10,000 Jews arrived through Galveston, eventually settling throughout Texas and the American West.

Before Galveston, Zangwill had put his enormously successful writing career on pause to join up with Herzl and the other political Zionists, but split when they refused to accept the idea, offered by Great Britain, of a Jewish state in Uganda instead of Palestine. Alarmed by the pogroms in Eastern Europe, Zangwill founded the Jewish Territorial Organization, known as the ITO, which tried to find a land without people for a people without a land. With the Palestine option seeming distant at best, the ITO saw Galveston as the next best thing. Jochelman, from Kiev, was the ITO’s agent on the ground in Russia.

“A Jewish homeland in Palestine was only one of several possibilities,” Cockerell writes in an introduction. “[A]s one character in the book says, ‘It’s never inevitable at the time.’”

Members of the Jewish Territorial Organization meet on June 1, 1905. Israel Zangwill sits at center, arms crossed, next to the woman in white. David Jochelman is the third sitter to Zangwill’s left, with his arms crossed. A photo of Theodor Herzl is at the rear. (Hashomer Hatzair Archives, Wikipedia)

Galveston is just one of the possibilities embodied in Cockerell’s family story. In New York City, her great-grandfather’s son by his first marriage writes experimental plays under the name Emjo Basshe. And in London, Jochelman’s daughters Fanny and Sonia share a rambunctious house at 22 Mapesbury Road with their husbands and their combined seven children. Fanny’s husband is a “reserved” Englishman, Cockerell’s grandfather Hugh; Sonia husband, Yehuda “Lova” Benari, was a personal assistant to Jabotinsky who moved his wife and children to Israel in 1951.

Cockerell tells the unusual story in an unusual way, by collaging excerpts from primary documents. The historical characters speak in their own words, culled from letters and published work. Contemporary newspaper accounts augment their stories, with all the acerbity and casual prejudices of their day. (The New York Herald describes the notoriously homely Zangwill as “the very archetype of his race – shrewd, witty, wise; spare of form and bent of shoulder, and with a face that suggests nothing so much as one of those sculptured gargoyles in a mediaeval cathedral.”)

Cockerell, 30, has a master’s degree in journalism. Her research for “Melting Point” took her to archives in Texas, Ohio, New York, London, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. “Melting Point” is her first book.

Earlier this week we talked via Zoom about family secrets, the serendipity of Jewish survival and writing about Jews and Zionism after Oct. 7.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

I want to start with how you tell this story: Why did you keep your own voice out of the body of the book and build the story with actualities and primary documents?

My first draft was very conventionally written, and then I read [the experimental novel] “Lincoln in the Bardo” by George Saunders, and I wondered if I could make a Russian-Jewish version of “Lincoln in the Bardo” about Jews going to Texas. I thought that the moments when the primary sources seem to interact with each other, even though [their authors] had been dead for 100 or more years, created a spark of energy that I really loved.

Tell me about your upbringing and what you knew of these stories before you started realizing you had this bigger story to tell.

I knew almost nothing of my dad’s side of the family. There was this huge, dusty portrait of my great-grandfather hanging in my family home in North London, and in this painting, he’s receding into the shadows. He looked like someone very much stuck in the 20th century. I never thought to ask a single question about him until maybe 2018 or 2019 when I wondered if there was anything more to him than what my family was saying, which was that he was a businessman who lost all his money after the Wall Street crash.

He was a Zionist activist, right?

Certain members of my family say he was at the First Zionist Congress, which I never found any proof for. But he was definitely at the second and third and fourth, and he saw Herzl speak, and he was at Herzl’s funeral. And then he was one of those who sort of abandoned the Zionist movement in this quite dramatic split [over the Uganda question]. He would almost have been the leader of the Jewish Territorial Organization, but he was too unknown, and he urged Zangwill to become the leader instead. But none of this was talked about.

Tell me about your Jewish identity growing up.

Almost none. My dad grew up celebrating Passover, but that’s not something that he continued. We always had gefilte fish balls in the fridge, and a jar of borscht in the cupboard. And that was it. I never celebrated Hanukkah, and didn’t speak a word of Hebrew or Yiddish or Russian. My grandmother’s mother tongue was Russian, but she wanted her children to assimilate and to become English. As a result, this heritage that I feel could have been mine did not become mine. Writing this book made me feel more of a sense of everything I lost, everything that fell away down the generations.

Let’s take those generations one by one. Your great-grandfather was a Zionist and later what we might call a “territorialist,” desperate to find a refuge for Eastern Europe’s persecuted Jews, even if it was in Texas. But his son by his first marriage, Emjo (short for Emmanuel Jochelson) Basshe, takes a different route. He moves from Russia to New York City and, like so many Jews of his era, is deeply involved in the theater and the arts, at one point becoming a principal in the New American Theatre, bankrolled by the Jewish financier Otto Kahn. Why was it important to tell his story?

I wanted the reader to be immersed in the melting pot of New York of the ’20s and ’30s, for them to see what it was actually like living in the melting pot. Emjo Basshe was born in the Russian Empire, moved to America when he was a child, and married this Southern belle from North Carolina and had a daughter, also named Emjo Basshe, or Jo, who is now in her 90s.

Jochelman’s daughters by his second marriage, your grandmother Fanny and her sister Sonia, meanwhile, shared a house in London with their husbands and children.

Like many other North London houses in the mid-20th century, it was this pocket of Russian Judaism, which hadn’t really melted into the melting pot, and didn’t until years later. The adults all spoke Russian, apart from my grandfather, Grandpa Hugh, who was this slightly buttoned up, reserved Englishman who was apparently a bit out of place in this mad, chaotic house.

Sonia is married to Yehuda Benari, a personal assistant to the Revisionist Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky. They move to Israel, and this branch of the family is going to keep a different version of the Jewish future alive.

Benari hero worships Jabotinsky, and in the late ’30s, he was going on these tours of Europe, urging European Jews to get out while they could, anywhere: to Palestine, or to America, to England or to somewhere else. In later years, he said the guilt that he felt that he wasn’t able to persuade the European Jews to leave Europe was something he never got over.

British Jewish playwright Israel Zangwill’s “The Melting Pot,” which opened in Washington, D.C. on Oct. 5, 1908, popularized a metaphor for how immigrants were expected to assimilate into American society. (University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections Department)

Were you always aware of your Israeli cousins?

I wasn’t. I think in 2018 or 2019 my dad’s cousin Mimi had an 80th birthday party at 22 Mapesbury Road, and her sister Judy and all Judy’s descendants came over from Tel Aviv. I think that was the first time that I became dimly aware that I had this whole branch of my family who had left London in the early 1950s and moved to Israel, never to return.

I feel your book is about, among other things, the different ways Jews seek to preserve and sometimes discard their identities. One, do you agree with me? And two, at what point did you come to an understanding that this would be what your family memoir would be about?

Yes, that’s in the title of the book, “Melting Point.” It was only about a year in that I realized that this is the story of assimilation and of melting into the melting pot for Jewish immigrants. But I think it’s also a universal experience of leaving a place and arriving in a new place, and part of your identity changing or dissolving away. My family definitely melted into the melting pot of London. You know, I think of myself as British, as a Londoner, more than I think of myself as Jewish or Russian or Russian Jewish. As I was writing the book, I was feeling a certain ambivalence about the melting pot and about assimilation and whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing. The jury’s still out.

I don’t know if he’s being prescriptive or descriptive, but Zangwill is pessimistic that Jews can retain their distinctiveness and what we might call continuity in the melting pot. His wife, Edith Ayrton, wasn’t Jewish. Is it odd that he would push so hard for Jewish resettlement in the American West?

He was quite paradoxical in terms of his ideas about American Judaism. He would say things like, “America is the euthanasia of the Jews. If I had my way, not a single Russian Jew would enter America.” But then he would also proclaim Galveston as the new Jewish homeland, and that the great American West was where the Jewish future lay. He would say one thing in public and another thing in private in a way that entranced me, and which seemed to reflect all my feelings about Judaism and immigration and the melting pot.

Do you know where your great-grandfather would come down on that question: Did Judaism have a future outside of a Jewish homeland?

I think he really believed in the Galveston project, and that America was at least a temporary Jewish refuge. Maybe he didn’t realize that it would become a permanent Jewish refuge, or a permanent Jewish homeland for most of the Galveston immigrants.

You also write that if not for Zangwill, you would not be you.

Just as the Galveston Movement was crumbling, my great-grandfather went on a trip to England and fell ill while he was there. He had been planning on moving to America. When I was researching, I found a letter in the American Jewish Archives from Jacob Schiff to Zangwill saying, “You know, Dr. Jochelman has just told me of his plans to move to America.” [Jochelman] accidentally found himself in England in 1914 and Zangwill wrote to him, “You must stay here. Your future belongs to England.” And so that’s why I’m British, just because of this piece of advice.

The first part of your book goes deeply into the debate among Jews and the British about establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine. You include accounts of the Kishinev massacre of 1903, which puts into context the fears and real danger that were motivating Jews to find a safe haven. Zionism wasn’t just people in top hats dreaming up a Jewish colony in Palestine, but a solution to a dire problem. But I have to ask: Your book comes out at a very fraught time when any subject that touches on Israel leads to a fierce and even ugly debate, and Jewish authors and books are accused of taking sides even if they don’t intend to. Has that been on your mind as you promote the book?

The book is told through primary sources, and it doesn’t really have an agenda. It doesn’t have a bias, and I hope that it, if anything, it just destabilizes the reader in their position about these things, because I felt quite destabilized while reading it. It’s so tempting to draw neat conclusions about things and to have unwavering principles about things. I hope that this book makes readers, if not change their mind, then just question things a little more.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.