Streit’s, the kosher food company that’s best known for its matzah, is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year.

And while many things have changed since the matzah bakery was first opened on Rivington Street on the Lower East Side in 1925 — most notably, the bakery left the city in 2015 for a bigger, more modern factory in Rockland County — one important detail remains the same: Streit’s is still run by the same Jewish family.

“It’s an honor to be doing what we’re doing for so long,” Aaron Gross, the great-great-grandson of founder Aron Streit, told the New York Jewish Week during a tour of their matzah factory last week. “We’re a family business. I think it’s amazing that we’ve made it this far. I don’t think many businesses make it to 10 years, let alone 100, owned by the same family, especially.”

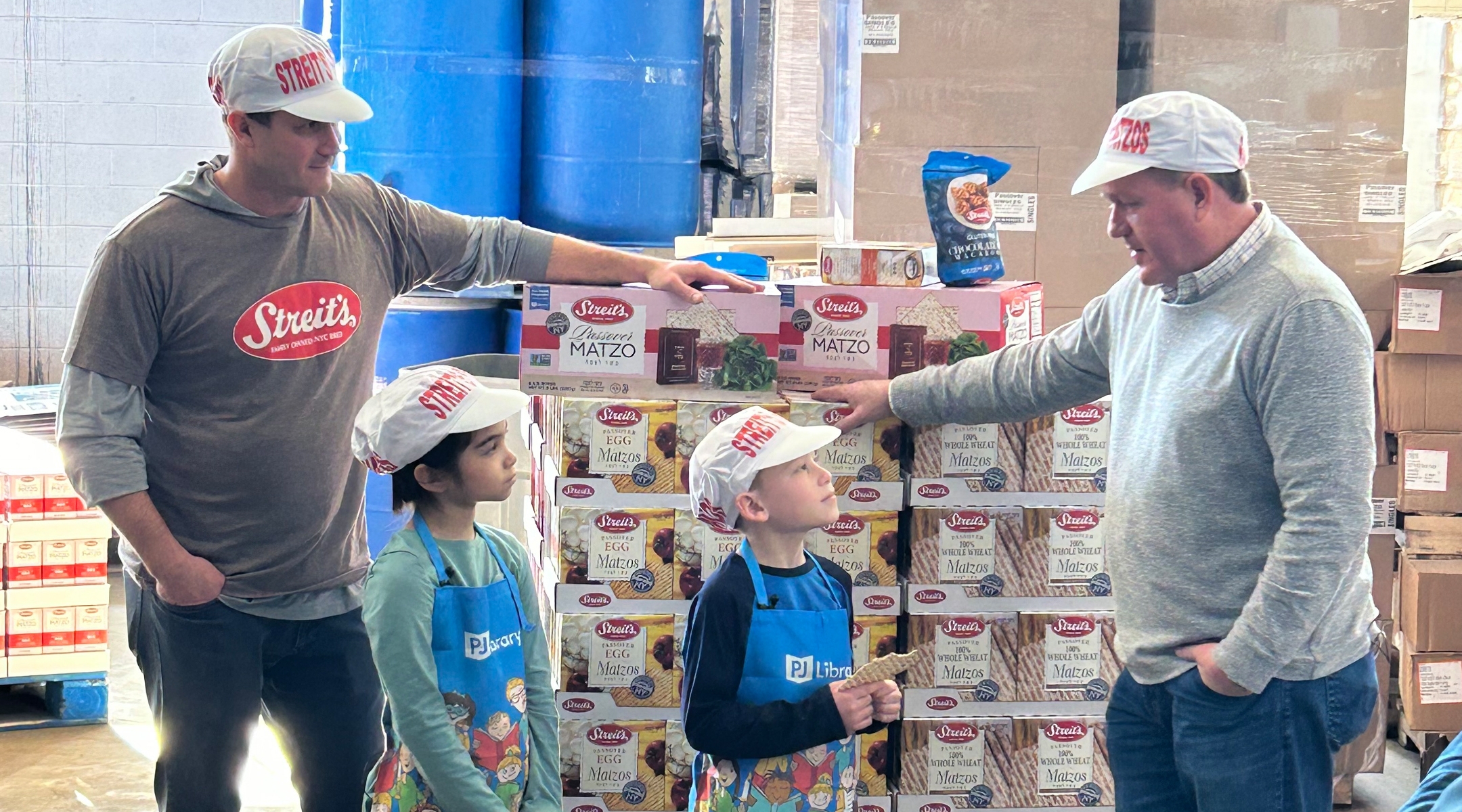

Gross and his cousin, Aron Yagoda, are co-owners of Streit’s (Aron Streit, Inc., officially), and are respectively fifth- and fourth-generation descendants of the original Aron. Family tradition is at the core of the company’s identity — not just on the leadership side of things, but also on the factory floor.

“There’s a lot of generational employees in the factory,” Yagoda said. “Some of their fathers are now bringing in their sons and daughters to work here as well. So it’s family inside and outside the factory.”

But family tradition isn’t just important within the company — it’s also intrinsic to their customer base, according to the cousins.

“There is a halachic value to the matzah we’re making. You have to have it on Passover,” Gross said of the obligation to eat matzah on on the first night of Passover, which this year begins on the evening of Saturday, April 12. “But we also want to create a memory, create a tradition that you want as well.”

Yagoda concurred. “Our family becomes part of their family by being on their table year after year after year, as it goes down through the generations,” he said. “Many times people will buy whatever their grandmother bought, which was whatever their grandmother bought.”

Yagoda added, “We take a lot of pride in making sure everyone has a nice seder and that Streit’s is part of it.”

When the duo gave the New York Jewish Week a tour of the factory on the last day in March, the busy season of pre-Passover production was already winding down. While most Jews start thinking about matzah mere weeks before the holiday begins, for Streit’s, their Passover season starts in the fall, after the High Holidays, with the manufacturing of essential matzah-adjacent Passover products like matzah meal, matzah farfel and cake meal.

Then, usually beginning in November to account for long transit times, they start baking and shipping Passover matzah overseas to their international customer base — which, this year, included Canada, Mexico, Turkey, South Africa and Israel, as well as some of Europe, according to Gross.

By that point, at least six rabbis are on-site 24 hours per day to ensure that everything is kosher for Passover. A rabbi will oversee the entire matzah-making journey, from the flour being processed at the company’s mill in Mifflinville, Pennsylvania, to the mixing of the flour and water, to the sheeter, which flattens the dough, and all the way through the oven. (There’s some urgency, too: To be kosher for passover, the dough must be mixed, flattened and baked within 18 minutes.)

Passover production for the U.S. market begins in December and runs through the winter. Gross said the company “really [tries] to push” quality and freshness. And as a New York brand whose factory is in Orangeburg, just about a half-hour drive from the city, Streit’s “could be making something that could be in the grocery store the next day,” he said.

“We’re a New York brand,” Gross added. “We really try to give these New York retailers the freshest matzah out there.”

By the time of our visit, production was shifting from Passover matzah to so-called “daily” matzah, so rabbis were no longer posted around the factory. Nonetheless, Streit’s matzah-making process continued unabated. According to Gross’ calculations, the factory produces about 108,000 sheets of matzah per day.

While the factory floor buzzes with the thrums of conveyor belts and sheeters, with a couple dozen employees scattered across the various stages of production, the area by the entrance functions as a sort of Streit’s museum, with old machines and tools from the original factory out on display. Here, the walls are adorned with century-old photos of rabbis surrounding stacks of matzah and men smoking cigars on the production line. (Not to worry: Gross said the 715-degree convection oven would’ve baked away the cigar smoke smell.)

The old machines looked like relics of a bygone era — and yet somehow, they had been in use until just 10 years ago. “We used basically the same technology that my great-grandfather used,” Yagoda said. “We didn’t do much [differently] from 1935 until 2015 when we moved here.”

Moving from the old Lower East Side factory to the new one essentially allowed Streit’s to leap a century in time. Buttons on screens now help fix machine jams that employees used to fix with wrenches, and high-tech robots now rapidly package the matzah.

Irving Streit, center, who was the son of founder Aron Streit, in an undated photo taken at the Streit’s factory on Rivington Street. (Courtesy Menemsha Films)

Though Streit’s has been settled in their new spot since 2017, the move from the city required some adapting. For example, Gross said it was “really important” to maintain the same flavor of matzah and replicate the process from the Lower East Side factory. One “very rare” aspect of their process, according to Gross, was the use of a convection oven to bake matzah, which is much hotter and creates a “more even, crispier bake” than more commonly found direct fire ovens. Streit’s bought a new convection oven for the new space — designed by Baker Perkins, the same manufacturer that they used on Rivington Street.

“One of our biggest concerns when we moved up here was retaining as many of our employees from Rivington Street as possible,” Gross said. “The guys we have out in the factory, they know matzah. They know how to bake matzah. They know what it’s supposed to taste like.”

(As such, the company kept many of their employees on payroll through the year-and-a-half pause between closing up shop on Rivington Street in 2015 and opening in Orangeburg in 2017. “It’s amazing that we still have a lot of these guys from down on Rivington Street,” he added.)

One employee, Michael Abramov, has worked in the Streit’s factory since 1989, when he was hired by the late Jack Streit, Aaron Gross’ grandfather, whom Abramov refers to warmly as “Mr. Jack.” From the age of 6 or 7, Abramov said he helped his mother make hand-made matzah back home in Uzbekistan.

Abramov said his work at Streit’s is fulfilling. “This is [a] very, very big mitzvah,” Abramov said. “This is already 100 years.”

To celebrate those 100 years, Streit’s has partnered with PJ Library, the program that provides free Jewish books to families, to include two origami-style “question catchers” inside each of the Streit’s five-pound boxes of Passover matzah. These small, interactive games — one designed for younger children, the other for older kids — “marry the tradition of imagining oneself in the Passover story to dynamic family-first Jewish experience that PJ Library is known for,” according to a press release.

“Anything we can do to get the younger generation involved in the holiday is important,” Gross said, “just passing on traditions.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.