This month, The New Yorker is marking its 100th anniversary as perhaps the country’s most influential magazine of longform journalism and literary fiction.

It has also been a home to pioneering writing by and about Jews. In its early days, under founding editor Harold Ross, the magazine seemed to stand for a certain kind of wry, WASPy sensibility that reflected the reading tastes of the elites of the city it was named for. Over the years, as the cultural landscape was transformed by diverse new voices, the magazine followed suit.

Ross’s legendary successor, William Shawn, was an assimilated Jew who seemed to look both backward to its roots and forward to its future. Among his Jewish successors was Robert Gottlieb, who came from the world of publishing, and, since 1998, David Remnick, who has managed to put out a weekly magazine and podcast while occasionally filing thoughtful profiles of pop stars (Bruce Springsteen, Leonard Cohen) and politicians (Bill Clinton, Barack Obama) and deeply reported articles about Israel.

Over the years the magazine has launched or nurtured the careers of a pantheon of Jewish writers: Cynthia Ozick, Philip Roth, Grace Paley, Saul Bellow, Jonathan Safran Foer, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Renata Adler, Bernard Malamud, Nadine Gordimer, Lore Segal, Nathan Englander, Ariel Levy and Ben Lerner, among others.

Like The New York Times, the magazine tends to track the obsessions of Gotham’s college-educated class, which includes a disproportionate number of Jewish readers. That is reflected in frequent nonfiction pieces about Israel, shifting from early sympathetic portrayals to center-left perspectives from journalists like Bernard Avishai and Ruth Margalit to, especially since Oct. 7, harsher critiques of the country from writers like M. Gessen.

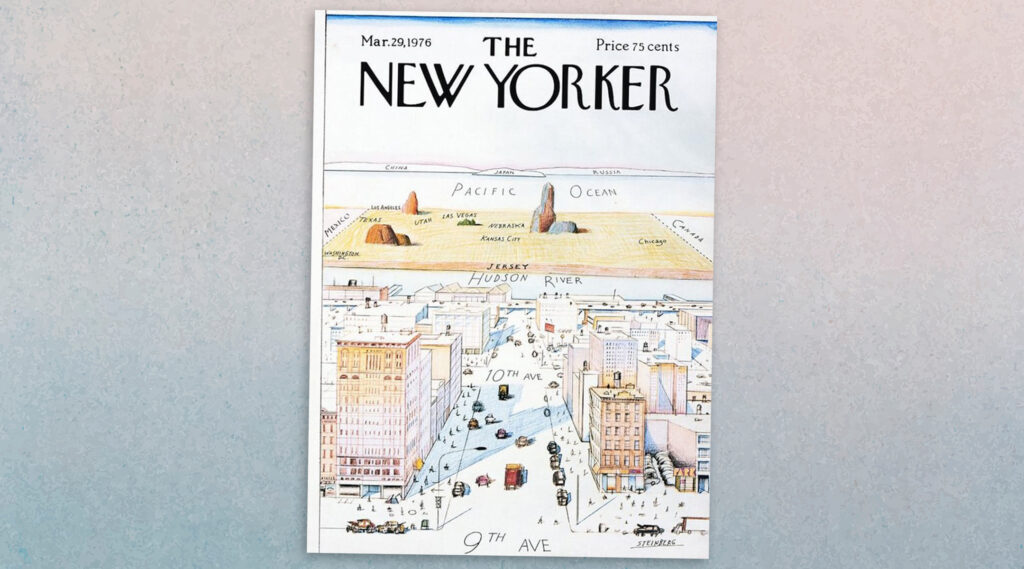

Of course, no retrospective of The New Yorker’s centennial can leave out the cartoonists: Jewish regulars have included Roz Chast, Liana Finck, Ed Koren, the former cartoon editor Bob Mankoff, David Sipress and Saul Steinberg (whose New York-centric March 29, 1976 drawing, titled, “View of the World from 9th Avenue,” may be the best-known cover in the magazine’s history).

Like the big stack of New Yorkers that you promise to get through, the Jewish history at the magazine is too much to take in at a sitting. Below is a highly selective list of Jewish highlights and controversies from The New Yorker’s century in print:

1. “Defender of the Faith,” by Philip Roth (March 14, 1959)

Roth’s riotous story about Grossbart, a conniving Jewish army recruit who asks for special treatment from his Jewish sergeant, led rabbis and other Jewish leaders to denounce the author as a shande fur de goyim — a traitor to his people. Responding to criticism that the story confirmed Jewish stereotypes — in a mainstream, elite publication like The New Yorker, no less — Roth declared that “Grossbart is not The Jew, but he is a fact of Jewish experience and well within the range of its moral possibilities.”

2. “Other People’s Houses,” by Lore Segal (March 18, 1961)

Lore Segal had published just a few stories in Commentary magazine when she submitted a manuscript to The New Yorker based on her experiences as a young girl sent from Vienna to England on the Kindertransport. The story, “Other People’s Houses,” was the germ of what became the remarkable autobiographical novel of the same name. Segal continued to publish in the magazine for the next 63 years, with her last story appearing two weeks before she died last October at age 96.

3. “Eichmann in Jerusalem,” by Hannah Arendt (February-March, 1963)

Arendt’s dispatches from the trial in Israel of the Holocaust’s chief engineer, Adolf Eichmann, has remained controversial ever since its publication over several issues of the magazine. That fall, Irving Howe, Lionel Abel and other members of the New York Intellectuals essentially put Arendt on trial over her reporting, saying the now famous phrase she used to describe the Nazis’ genocidal enterprise, “the banality of evil,” minimized Eichmann’s crimes. Worse, many said, Arendt had shown remarkably little empathy for the Jewish councils and concentration camp prisoners forced into collaborating with their tormentors. The controversy around “Eichmann” would dog Arendt for the rest of her life, and overshadow her political philosophy about the origins of totalitarianism.

4. “Hassidic Tales, With a Guide to Their Interpretation by the Noted Scholar,” by Woody Allen (June 20, 1970)

Before his reputation was tarnished by scandal, Woody Allen was a comedic cyclone: a stand-up comedian, actor, screenwriter and movie director. Starting in 1966, when The New Yorker published the first of dozens of his pieces, he could add “writer.” His earliest “casuals,” as they were known at the magazine, were derivative of another New Yorker legend — the Jewish humorist and playwright S.J. Perelman — but he eventually found his voice in stories like this 1970 parody of German-Jewish philosopher Martin Buber’s retellings of classic Hasidic stories. (“Rabbi Zwi Chaim Yisroel, an Orthodox scholar who developed whining to an art unheard of in the West…” is how one of Allen’s tales begins.) “Hassidic Tales” was included the next year in “Getting Even,” the first of three classic collections of Allen’s humor.

Saul Steinberg’s New York-centric “View of the World from 9th Avenue” may be the best-known cover image in the magazine’s history. (Courtesy The New Yorker)

5. “The Lower East Side: A Sunday-Morning Tale,” by Calvin Trillin (Feb. 16, 1973)

Starting with a three-part piece on desegregation in 1963, Trillin has been writing for the magazine for 62 years. In addition to covering civil rights, murders and Americana, Trillin — who grew up Jewish in Kansas City, Missouri — writes regularly about food, as in this love letter to an ever-changing New York. “A Sunday-Morning Tale” was inspired by news that Ben’s Dairy on Houston Street, where Trillin would buy homemade cream cheese with scallions, started closing on Sundays. “I took it personally,” writes Trillin, who can’t imagine his Sunday routine without Ben’s. “The pleasure of a late breakfast that could be extended to include picking at the small bits of Nova Scotia left on the platter at three-thirty or four was gone.”

6. “The Shawl,” by Cynthia Ozick (May 19, 1980)

In addition to writing critical essays for the magazine, Ozick published a number of short stories, including “The Shawl,” one of the most harrowing pieces of fiction ever written about the Holocaust. In what a colleague called “spare, meticulous prose,” Ozick writes about Rosa, a woman in a concentration camp who is trying to keep her baby hidden from the guards. The story won the O. Henry prize, and a sequel, the novella “Rosa,” also appeared in the magazine. Discussing the story, Ozick, who was born in New York in 1928, compared her life as an American Jew to that of her Eastern European contemporaries. “I was having the life that Anne Frank would have had simultaneously,” she told an interviewer. “I can never think of my high school years without realizing how normal they were, and how, at that very moment, the chimneys were roaring away.”

7. “Holy Days,” by Lis Harris (September 1985)

Harris’s two-part series about the Lubavitcher Hasidim may have been the most sympathetic and intimate portrayal of an Orthodox Jewish community since Chaim Potok’s 1967 novel “The Chosen.” In immersing herself with a welcoming Chabad family, Harris not only demystified Jewish ritual but described her own spiritual awakening as a result of her assignment.

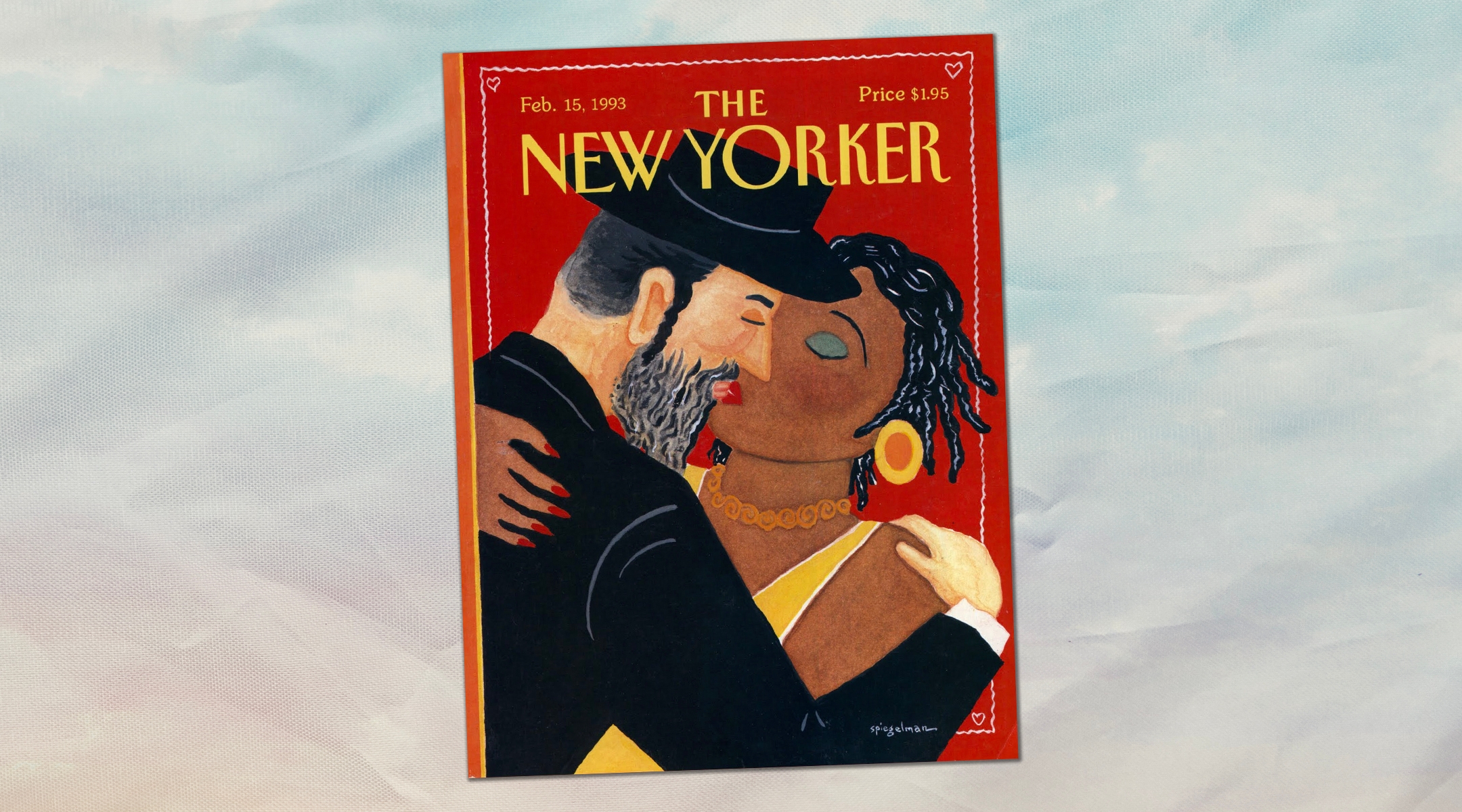

8. “The Kiss,” by Art Spiegelman (Feb. 15, 1993)

Art Spiegelman called his Valentine’s Day cover, featuring a Hasidic man and a Black woman (who the artist said was not Jewish) locked in a romantic kiss, a metaphor for the “reconciliation of unbridgeable differences.” The cover was criticized by Hasidic leaders, who said the image flouted their community’s customs of sexual modesty and trivialized racial tensions in Crown Heights, the Brooklyn neighborhood where 18 months earlier a yeshiva student was killed during three-days of anti-Jewish violence. A Black clergyman, meanwhile, said the cover played on stereotypes of white dominance and Black submission.

9. “A Purim Story,” by Adam Gopnik (Feb. 10, 2002)

Asked by New York’s Jewish Museum to deliver a “spiel” (a parodic sermon) at its black-tie Purim Ball, Gopnick uses the occasion to ruminate on his own highly assimilated Jewish background. (How assimilated? At one point he wonders if Purim is the holiday with “the little hut in the backyard.”) Gopnick reaches out to Jewish scholars to learn more about the holiday and the often knotty book of Esther, ultimately concluding (no doubt to the chagrin of traditionalists) that, outside of religious circles, Jewish humor itself had become for many the last vestige of Jewish belonging.

10. “Converting to Judaism in the Wake of October 7th,” by Jeannie Suk Gersen (Dec. 2, 2024)

Many Jews have been critical of The New Yorker’s coverage of Israel during its war with Hamas, objecting that writers like M. Gessen are one-sided in reporting on the conflict and show too little understanding of the trauma of Oct. 7. This essay by Jeannie Suk Gersen was a notable exception, as she writes about how in the wake of the attacks “rabbis from a broad range of Jewish institutions observed something they hadn’t anticipated: a surge of interest in Judaism.” Gersen is part of the surge: The daughter of immigrants from North Korea, she writes about her becoming a Jew by choice under the guidance of Rabbi Angela Buchdahl at New York’s Central Synagogue. The piece is a snapshot of the present moment, including perspectives from “mainstream” Jews devastated by the Hamas attacks and anti-Zionists who are also seeking a home in Judaism.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.