A unique Holocaust art exhibition opened this week in New York’s City Hall.

In “The Wandering Jew,” a 1947 oil-and-canvas painting by Dutch artist Eliazer Neuberger, a barefoot man wearing torn garments gazes forward while behind him an elderly mysterious figure who evokes the prophet Elijah raises his hand in blessing.

A 1945 pencil-and-watercolor drawing by Russian soldier-artist Zinovii Tolkatchev shows the joyous moment his Soviet Red Army comrades arrived to liberate Jewish prisoners at Auschwitz.

And Poland’s Jakob Cymberknopf depicts a rather cheerful, pastoral scene in “View of Büchenwald,” which expresses the artist’s renewed sense of freedom shortly after liberation.

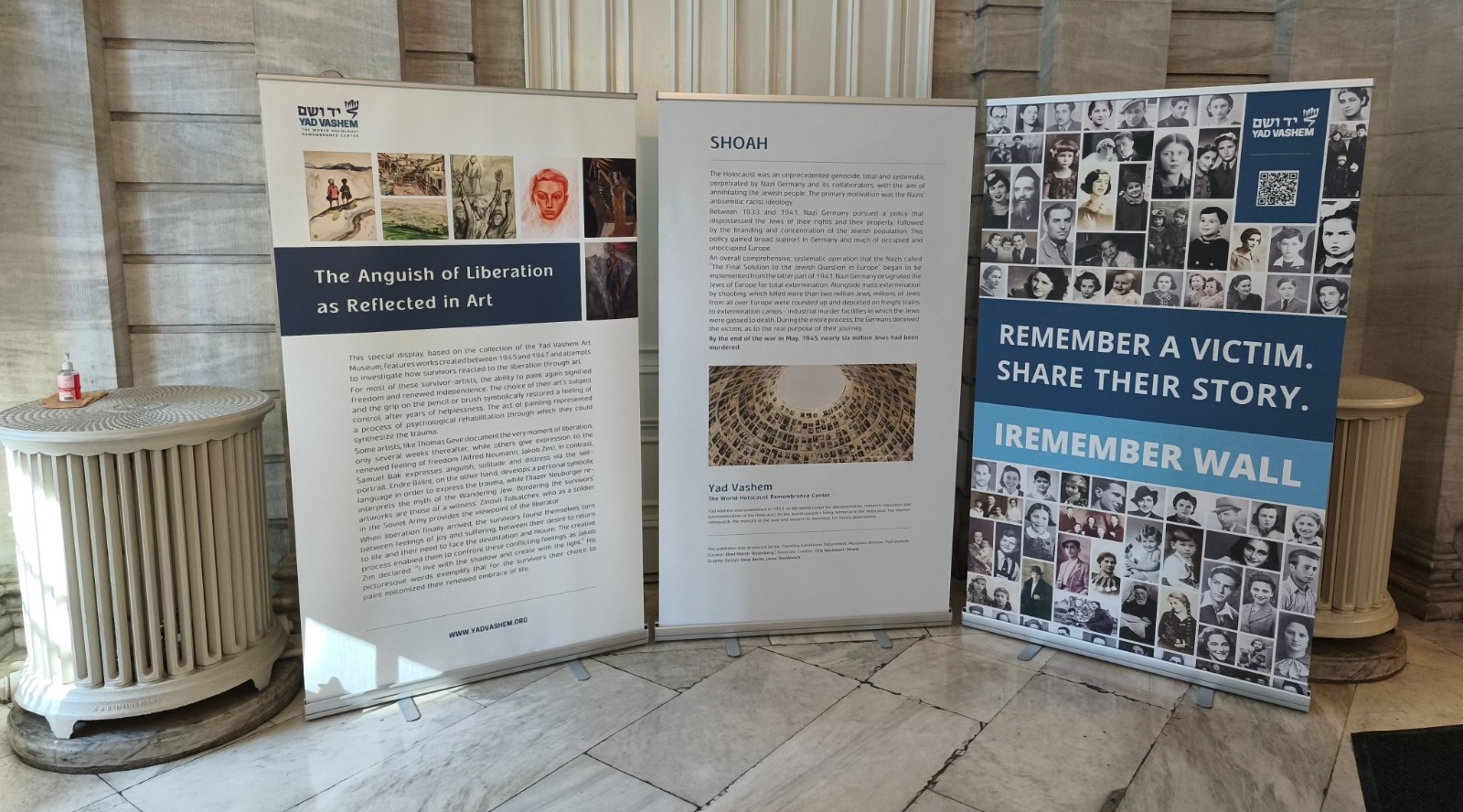

These three paintings and sketches are part of a weeklong exhibit titled “Anguish of Liberation as Reflected in Art,” curated by Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, and features 11 works created between 1944 and 1947 by liberated Jewish survivors of the Holocaust.

The exhibit is on display for the week of International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the concentration and extermination camp. The exhibit was sponsored by New York City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams with Council Member Eric Dinowitz and Yad Vashem Chairman Dani Dayan. The opening event on Wednesday evening was attended by some 200 public officials, including U.S. Rep. Dan Goldman, Jewish community leaders, City Council members and Holocaust survivors. It marked the first time Yad Vashem has ever displayed art at New York’s City Hall.

“We do not use the word ‘celebrate’ to mark the liberation of Auschwitz,” Dayan said. “During 1944 and 1945, all the Jews of Europe and North Africa were liberated from the brink of extermination, but for those Jews and the entire Jewish people in general, it was far from a happy occasion. Liberation came too late. Many survivors found themselves hopeless, destitute — the sole surviving members of their families. In some cases, they even were the only remnants of an entire community.”

The art exhibit is one of two Holocaust-related events Yad Vashem organized in New York this week. The second is the dedication of a street on East 67th Street and 3rd Avenue as Yad Vashem Way. The Jan. 30 street naming ceremony marks the first time a street in the U.S. honors the Israeli institution dedicated to memorializing the Holocaust.

Both the art exhibit and the street dedication reflect New York’s importance as home to the world’s largest concentration of Holocaust survivors outside of Israel. After World War II, survivors came to the United States with almost nothing and rebuilt their lives, families and careers—many of them living on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, where Yad Vashem Way is located.

The New York City Council’s decision to honor these survivors and their achievements is a sign of the city’s commitment not just to remembering the Holocaust but also to combating Jew-hatred, Dayan said.

“We are co-naming a street in a city whose mayor is a staunch ally in the fight against antisemitism,” said Dayan, who served as Israel’s consul-general in New York from 2016 to 2020 before assuming his current position as head of Yad Vashem in August 2021.

Yad Vashem Chairman Dani Dayan, center, tours an exhibit of Holocaust art on New York’s City Hall with New York City Deputy Mayor Fabien Levy, left. (Courtesy of Yad Vashem)

Israel is now home to 120,000 Holocaust survivors, with more or less an equal number living in the Diaspora, according to Dayan. Last year, about 120 people applied to be one of six torchbearers for Israel’s annual Yom HaShoah, or Holocaust Remembrance Day; this year, Yad Vashem received only 75 applicants—a reflection of the dwindling number of survivors.

“This is unfortunate but inevitable,” Dayan said. “I hope it will take many years, but at some point we will live in a world without witnesses.”

Keith Powers represents New York City’s Council District 4, which includes the Upper East Side as well as Park East Synagogue, an Orthodox congregation whose members include many Holocaust survivors. Among them is its senior rabbi, Arthur Schneier.

“They came forward with the idea of renaming the street, and I agreed it was a great idea; we often do this to memorialize an important part of history,” said Powers, who is Catholic. “My hope is that when New Yorkers walk down East 67th Street and see this co-naming of Yad Vashem Way, they’ll open up their phones, Google it and learn some history.”

As a New York City councilman, Powers said he has pushed to treat acts of vandalism against synagogues and Jewish cemeteries as hate crimes—especially since the Hamas attack of Oct. 7, 2023.

In 2024, Jews were targeted in 345 hate crimes across the city’s five boroughs, more than all other minority groups combined. In May, for example, a Brooklyn man was charged with attempting to run down a group of Orthodox Jews with his car; only two weeks later, someone defaced the façade of Park Avenue Synagogue on East 87th Street with pro-Palestinian graffiti.

“What’s happening in New York City and throughout the country has been horrific to watch,” Powers said. “It is essential that we remind people of our duty to stand up for the Jewish community and make sure nothing like this ever happens again.”

The works at the City Hall survivors’ art exhibit are not original, but rather special museum-quality panels that showcase the images of the original works of art housed at Yad Vashem in Israel.

“Some of these artists imagined beautiful scenery in order to escape, and some depicted their experiences during the Holocaust. After liberation, these survivors were finally able to express themselves as individuals—something the Nazis tried to steal from them,” said Simmy Allen, Yad Vashem’s international media spokesperson.

“Many of these were created in displaced persons camps on the same location of former concentration camps in Europe,” Allen said. “It’s a very moving, impactful exhibit that features how survivors reconnected with their humanity and began the rehabilitation process to build themselves up from zero. Art is one of the most therapeutic methods of addressing trauma—these survivors used this medium to depict their emotions.”

Yitzhak Zuckerman, one of the leaders of the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto uprising, recalled years later that his January 1945 liberation was “the saddest day of my life.”

Nevertheless, Dayan noted, “The examples shown by the survivors—they grew, had families and contributed to every walk of life—is really a source of inspiration to all of humanity, for past, present and future generations.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

This article is sponsored by and produced in collaboration with Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center. This story was produced by JTA’s native content team.

More from Yad Vashem