(JTA) — Paul Kling was 14 when he played violin for a newly written opera, surrounded by sickness and death, in the Czech concentration camp of Theresienstadt.

He was rehearsing his part in “Der Kaiser von Atlantis” (“The Emperor of Atlantis”), written by the Czech-Jewish composer Viktor Ullman in 1943. Theresienstadt, about 30 miles north of Prague, served a distinct purpose from other Nazi camps. Among its inmates were famed Jewish artists and writers who put on concerts and plays, encouraged by the Nazis as propaganda to conceal their deportations and killing centers.

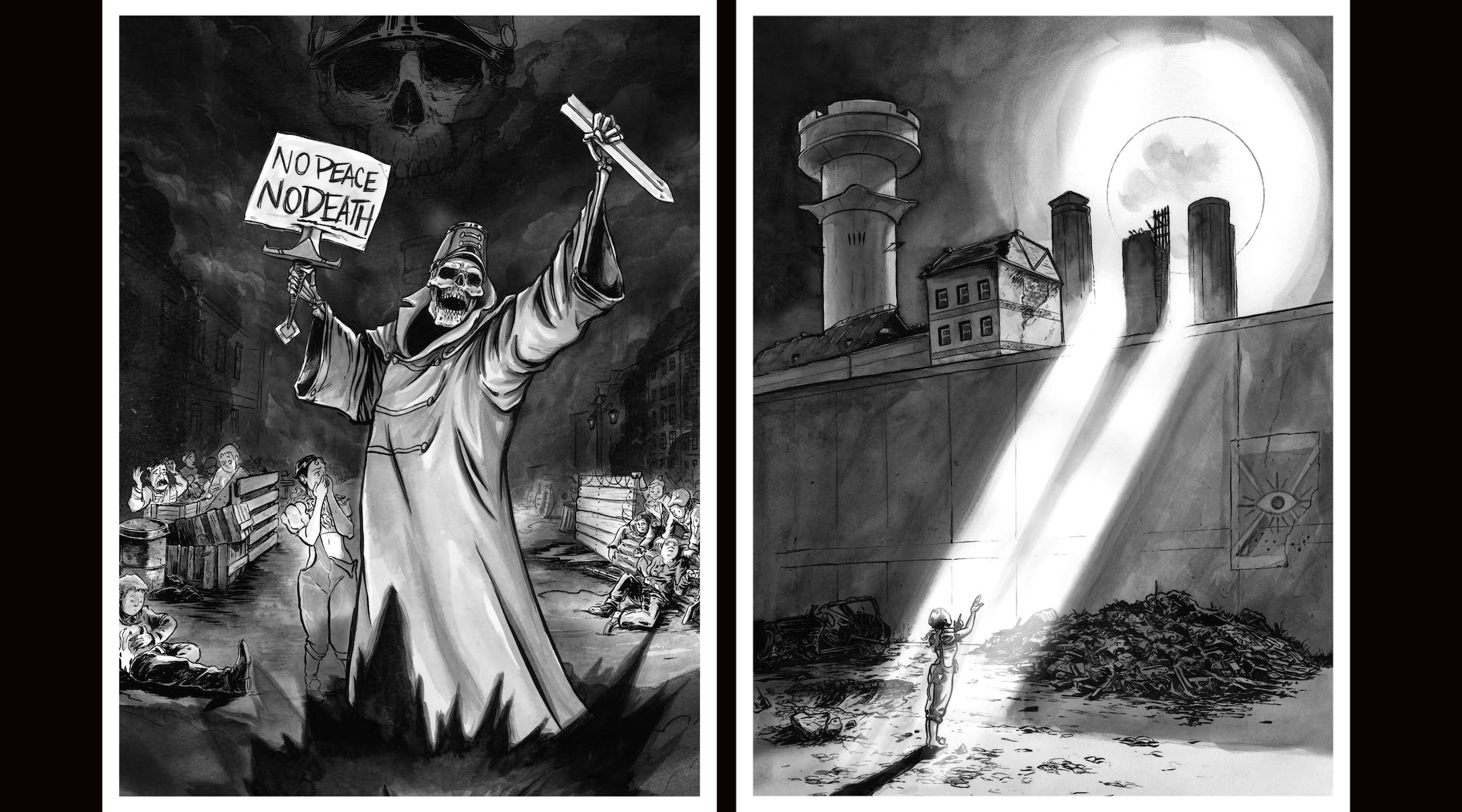

Ullman’s opera told the story of Death, personified as a soldier so overworked by a warmongering dictator that he goes on strike, which leads to a whirl of confusion when people cease to die. Though Kling played in rehearsals for “Der Kaiser von Atlantis,” the opera was never performed in Theresienstadt — perhaps because the Nazi guards suspected a parallel to their own dictator, or simply because the musicians were already being transported to Auschwitz.

Ullman and most of the ensemble members were killed there. But during a death march leaving Auschwitz at the end of the war, Kling escaped, lay down among dead bodies in the snow and survived. After the war he made his way to Kentucky, where he became concertmaster of the Louisville Orchestra in 1957.

Now, the Louisville Orchestra is staging the opera that Kling rehearsed in Theresienstadt. The one-night performance on Saturday comes just before International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

“It felt like we actually owed it to his memory to present this music,” said Teddy Abrams, the orchestra’s music director and one of several Jewish members behind the production.

The performance will also feature projections from the 2024 graphic novel “Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis,” which reimagined the opera through dystopian sci-fi and zombie horror.

Charles Brestel, a violinist in the orchestra for the past 49 years, arrived to study with Kling at the University of Louisville School of Music in 1971. He remembers Kling as a “formal” man who always wore a coat and tie. As a teacher, he stood out from the stern instructors that Brestel was used to, encouraging the students to collaborate instead of compete. Brestel credits him with his entire career as a violinist.

“Once, when I did get discouraged and announced I was leaving the school, he let me go out the door,” said Brestel. “About two or three weeks later, he gave me a call at my home 80 miles away and said, ‘Come and see me.’ And so I did, and I ended up back in school.”

The Czech-Jewish composer Victor Ullman, left, was murdered during the Holocaust; Pavel Kling, right, survived and later became the concertmaster of the Louisville Orchestra. (Courtesy Louisville Orchestra)

When Ullman suspected that he was headed to Auschwitz, he entrusted his works to his friend Emil Utiz, a Czech-Jewish philosopher who was in charge of the library at Theresienstadt. Utiz survived and handed the manuscript of “Der Kaiser von Atlantis” to another survivor, the prominent writer Hans Günther Adler.

But the work was thought to be lost for 30 years, according to Adam Millstein, a violinist and producer of the opera in Louisville. Millstein also works with Recovered Voices, an initiative to promote and perform music by composers whose work was suppressed or lost under the Nazis.

Then, in 1975, a British conductor who was researching Theresienstadt discovered that “Der Kaiser von Atlantis” had been collecting dust in Adler’s attic in London the whole time.

Why hadn’t Adler shared the music? “This is a question that comes up a lot,” said Millstein. “Some people ask, why weren’t these composers promoted more by others who survived and knew the composers? We don’t know the exact answer, but we can make a very educated guess that the trauma of this experience was so much that many did not want to delve back into the music.”

Louisville’s production coincides with the release of a new documentary, “The Lost Music of Auschwitz,” following the composer and conductor Leo Geyer as he pieced together music written by Auschwitz inmates and had an orchestra perform the lost works. Music was an integral part of Auschwitz, where the Nazis forced prisoners to perform while trains arrived, while people were killed or just when the guards wanted entertainment while they relaxed with a beer.

An Israeli ensemble performs a musical piece composed by Jewish Holocaust victims during a concert organized at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem, Nov. 21, 2016. (Menahem Kahana/AFP via Getty Images)

In 2021, Janie Press founded the group Holocaust Music Lost & Found to unearth music written in the camps and revive it through concerts across the United States. She said that she has seen “extraordinary” attention to Holocaust music in recent years, giving her hope that more melodies will be rescued from history.

“I don’t know how much more music there’s left to be found, but there’s always the hope that in somebody’s attic there will be a trove, a suitcase or a box,” said Press.

“Der Kaiser von Atlantis” has been performed sporadically around the world since the 1970s. Though it remains a relatively obscure opera, it has imprinted the lives of people who champion its recognition — including Tomer Zvulun, the production director of the show in Louisville, who also heads Atlanta Opera.

Zvulun first saw a version of “Der Kaiser von Atlantis” as a young man in Israel in the 1990s. Later, he assisted a director putting on the opera at Boston University. And in 2020, while other opera companies were shuttered during the COVID-19 pandemic, he led a production of “Der Kaiser von Atlantis” with the help of a socially distanced circus tent on a baseball field for Atlanta Opera.

Panels from “Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis,” the graphic novel version of “Der Kaiser von Atlantis” will be projected during the Louisville Orchestra’s staging of the Holocaust opera of the same name. (Courtesy Louisville Orchestra)

“That idea of artists that are trying to perform despite outside obstacles — a pandemic, in our case, or back when they tried to rehearse it in Theresienstadt — that, to me, is a very powerful story about perseverance and artists defying the odds,” said Zvulun.

Graham Parker, the Louisville Orchestra’s chief executive, had not heard of the opera before Abrams introduced him to it. But he said that celebrating Kling’s memory was important for the city’s Jewish community. When the orchestra was born, many of its first members were Jews.

“The orchestra has had a really deep connection to the Jewish community in Louisville since its founding in 1937,” said Parker, who is also Jewish. “After a catastrophic flood in the city, when the orchestra was formed, many of the first players came from an orchestra that was playing at the Jewish YMHA,” or the Young Men’s Hebrew Association of Louisville.

According to Millstein, this opera doesn’t just uncover a part of Louisville’s Jewish history. The story told through the music reveals a world of Jewish exploration that Ullman found in a concentration camp.

“Most of these composers were assimilated, most of them weren’t practicing, they were only labeled as Jews as a result of the Nazi racial laws,” said Millstein. “When Ullman was arrested and then sent to Theresienstadt, interestingly enough, that’s when he first started to really explore his Judaism, Jewish roots and Jewish themes.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.