In the early 1920s, a Jewish filmmaker set out to create a movie that would counter the rising antisemitism of the time.

The result was “Breaking Home Ties,” a silent film about Russian Jewish immigrants in the Lower East Side that depicts Jews and Jewish practice in a sensitive light.

“Breaking Home Ties” premiered at the Astor Hotel near Times Square in 1922. For its time, it was seen as a rare, well-rounded depiction of Jewish characters, and a glimpse into the lives of struggling immigrants.

Shortly after its premiere, however, “Breaking Home Ties” vanished into obscurity. That is, until it was discovered in a film archive in Berlin in 1984. And now, after an extensive restoration over the span of decades, “Breaking Home Ties” will once again hit the silver screen as part of the New York Jewish Film Festival, which opens on Thursday with a screening of “Midas Man,” a film about the Beatles’ Jewish manager, Brian Epstein.

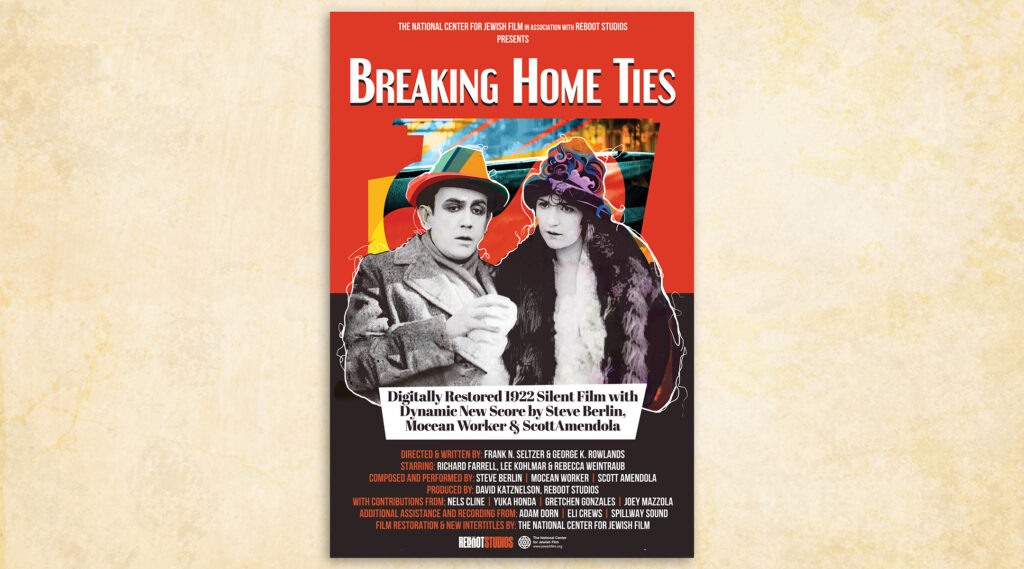

“Breaking Home Ties,” featuring a new, contemporary-sounding score commissioned by Reboot Studios and composed by Steve Berlin (Los Lobos), Mocean Worker (aka Adam Dorn) and Scott Amendola (Charlie Hunter/Amendola Duo), will screen on Sunday, Jan. 19 at noon at the Walter Reade Theater (165 West 65th St.) — just a 15-minute walk from where it opened over a century ago.

“To be able to see something from 100 years ago, that speaks to its own period but also the themes of today — it’s really a marvel to see,” said Lisa Rivo, co-director of the National Center for Jewish Film, which led the film’s decades-long restoration.

Rivo added, “I always say that seeing a silent film with music is like a bit of time travel, because you have artists spanning over 100 years working together.”

The film follows the life of a young man named David Bergmann — and, eventually, his parents and little sister — as they immigrate from Russia to New York City.

While David parlays his “good education in St. Petersberg” into a successful career as a lawyer in the New World, his destitute parents face much harsher circumstances upon their arrival in New York. His father struggles as a street vendor, and he and his increasingly frail wife are unable to afford a room in the Jewish Home for the Aged.

“In terms of the realities of immigrant life, [the film] really doesn’t shy away from that at all,” Rivo said.

Further complicating the Bergmanns’ circumstances: David and the rest of his family have difficulties reuniting. David, unclear of his family’s whereabouts, hires an investigator to track them down, to no avail. Meanwhile, David’s family has trouble locating him, unaware that he’s changed his last name to Berg. “They didn’t speak the language, they didn’t have any money, they didn’t have any resources, and they’re desperately trying to find their son,” Rivo said.

Plenty of films have been made about immigrants in turn-of-the-century New York — including “Hester Street,” the 1975 film also being shown as part of the festival. But in 1922, the year Frank N. Seltzer and George K. Rowlands co-directed the film, the Ellis Island immigration boom was still ongoing (albeit on its last legs). “I think this was the life that people knew [at that time]. If it wasn’t the creatives themselves then it was their parents, maybe their grandparents,” Rivo said. “But oftentimes it was the people who were creating the film, literature and art themselves that had experienced the dislocation of being an immigrant — and you really do feel that in the film.”

In addition to the unromanticized depiction of the immigrant experience — for example, Bergmann’s father is chastised by a policeman after misreading traffic signs, causing him to get hit by another vendor’s pushcart — the film stands out for its prominent and quite human depiction of Jewish characters. That, according to Rivo, is uncommon for films of that period. “Most of the Jews that are seen on film [at the time] are not explicitly called Jews,” she said. “And if they are, then they certainly are not treated with this kind of, not just respect, but depth of character.”

Unusually, practically all the main characters in “Breaking Home Ties” are Jewish. They’re seen lighting Shabbat candles and praying at a Yom Kippur service as drama unfolds around Bergmann’s love life — turns out his girlfriend back in Russia has left David for his best friend.

According to letters written by the producers, Seltzer wanted explicitly to make a film that would douse the flames of rising antisemitism being fanned at the time by Henry Ford and the Ku Klux Klan. “And his pitch was, ‘Let’s make a good, solid, entertaining romantic melodrama that has Jews as central characters, and in a normative way,’” Rivo said. “I think it was very innovative. It’s countering antisemitism without talking about antisemitism.”

Of course, the most fascinating part of the film may very well be the fact that we can watch it today. About 70 percent of the thousands of American silent-era feature films are believed to be completely lost, according to a 2013 Library of Congress survey. Another five percent have survived in an incomplete form.

(Courtesy National Center for Jewish Film)

“Breaking Home Ties” hadn’t achieved much success after its debut in America, according to Rivo, being eclipsed by “Hungry Hearts,” another Lower East Side Jewish tale released the same month.

But the film made its way overseas, and the only surviving print was found with German intertitles. “So that tells us that someone was investing some money in creating new materials to show for the local audience there,” Rivo said.

In the 1980s, Rivo’s mother — Sharon Pucker Rivo, who co-founded the Brandeis University-based National Center for Jewish Film — visited Germany. When curators showed her the film they’d dug up from their Berlin archive, none of them had any clue what it was. But between the menorahs, the Magen Davids and the tallits depicted on the film, there was enough visible Jewish content that they offered it up to the NCJF.

Upon returning home, the NCJF connected with Joe Eckhardt, a history professor at Montgomery County Community College outside Philadelphia and an expert on Betzwood Studio in Valley Forge, where the film was shot. He was able to translate the intertitles back to English, and identified the movie as “Breaking Home Ties.”

The film itself was very badly damaged; some of the perforations had been ripped and the footage was distractingly jumpy. “It was heartbreaking,” Rivo said.

And so, the NCJF undertook “quite an extensive film-to-film restoration” to rescue the film, and around 2010, enabled by the advancement of digital technology, the NCJF sent the film out to labs for yet another round of restoration.

“We were thrilled we were able to save this gem,” Rivo said.

The final touches came during the COVID-19 pandemic, when a group of Emmy-winning artists wrote and recorded the score that underpins the film. The music incorporates sounds of modern jazz, oscillating between background ambience and intense bursts that mirror the story’s rising tension. It’s probably the first time you’ll hear an electric guitar in a silent film.

Some other highlights of the New York Jewish Film Festival at the Walter Reade Theater (165 West 65th St.)

“Midas Man” (2024) | Jan. 16

Sixty years after The Beatles’ iconic performance on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” their seismic impact on pop culture continues to reverberate — and it may never have happened without the help of their manager, Brian Epstein. Join director Joe Stephenson and writer Brigit Grant at the film’s NYC premiere, and for a post-screening discussion of their film that tells the story of Epstein, who, as a gay Jewish man, was “an eternal outsider in British culture before dying at age 32 of an accidental drug overdose.” The film screens Thursday, Jan. 16 at 2:30 p.m. and 8 p.m.; get tickets here.

“Hester Street” (1975) | Jan. 18

Another film about Jewish immigrant life in the turn-of-the-century Lower East Side, “Hester Street” stars Carol Kane, whose performance as Gitl earned her a Best Actress Academy Award nomination. A wife and mother who recently arrived in NYC from Eastern Europe, Gitl is taken by surprise at how much her husband, Yankel (Steven Keats), has already assimilated to the new world. Watch this 50th anniversary screening on Saturday Jan. 18 at noon; standby tickets only.

“Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire” (2024) | Jan. 19, Jan. 21

In this new documentary about Elie Wiesel, the renowned Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate who authored the memoir “Night,” filmmaker Oren Rudavsky goes deeper into Wiesel’s “philosophically abundant inner life.” Enriched by access to his personal archives and told with “tenderness and nuance,” the film presents Wiesel — in many ways a private man, despite being one of the most public voices of Holocaust remembrance — in “newly intimate ways known only to his closest friends.” The film screens Sunday, Jan. 19 at 2:30 p.m. and Tuesday, Jan. 21 at 4:30 p.m.; standby tickets only.

This year’s New York Jewish Film Festival runs Jan. 15-29; click here for additional information.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.