Wearing Nikes, a hoodie, jeans with tzitzit and a kippah, Tamir Goodman weighed the basketball in his hands. He towered over nearly everybody in the gym — the 11-to-14-year-old students especially, but at six-foot-three, he had a few inches on the teachers and guests who came to see him, too.

“Hands ready, feet ready, mind ready,” Goodman repeated during a drill. He’d just run layup lines and given the boys’ and girls’ basketball teams at the Shefa School a lesson on the jump shot. But naturally, the kids wanted to see Goodman — who was once dubbed the “Jewish Jordan” by Sports Illustrated as a top-25 high school player in the country — in action.

“I can’t move no more,” he told one of the team’s coaches. Goodman’s professional career in Israel ended in 2008 after a series of injuries, and it had been 25 years since his anointment by Sports Illustrated.

So during the school visit, Goodman teamed up with his son, Matanel, who did most of the running around, while Tamir operated as point guard, zipping behind-the-back passes and hitting jump shots over his bold, but ultimately undersized, b’nai-mitzvah-aged competitors. He stuck around after the scrimmage to sign autographs for the eager middle schoolers.

Goodman’s visit was a big deal for students of Shefa, a Jewish day school on the Upper West Side for children with language-based learning disabilities. The kids likely weren’t big fans before his visit — none of them had been born by the time he retired from playing.

But this was a chance to meet a role model they could relate to. For starters, Goodman was visibly Jewish on the court: He wore a kippah and observed Shabbat while playing Division I college basketball for Towson University.

But what resonated with students most was that Goodman himself has dyslexia. “I still can’t really write,” he told the New York Jewish Week in an interview. To write his new children’s book, “Live Your Dream: The Story of a Jewish Basketball All-Star” — published Wednesday — he dictated it.

Now, Goodman hopes that the book, which is produced and published by PJ Library and focuses on how he overcame his struggles with dyslexia, will help the next generation do the same. “I feel like once the kids read this book, they could hopefully have the tools to feel empowered,” he said.

A pair of fifth-graders politely ask Goodman for his autograph during their Q&A session. (Joseph Strauss)

The book depicts a young Goodman finding it impossible to read and do math. It wasn’t until eleventh grade that he was diagnosed with dyslexia — and his doctor pointed out that his unique processing may have benefits outside the classroom. “It was true,” the book’s narrator says. “On the court, Tamir could picture in his mind where his teammates were located. He could tell in seconds who would be open for a pass, even before the player himself knew it.”

Goodman added in our interview, “A lot of times, people that are dyslexic are very creative with problem solving, very innovative.” Goodman said that the court vision from his dyslexia is what gave him his confidence while playing. “And I felt like I wanted to write the book so we could give kids a boost of confidence at a time that they might want to feel the opposite of that.”

Goodman’s goal seemed to be materializing among the Shefa School’s fifth-graders. A 10-year-old student named Clara said, after reading the book, “I learned that learning disabilities are actually because you have so much knowledge, that it all squeezes together.”

The connection between Goodman and Shefa is not a new one. Over the last few years, students had met Goodman during Shefa’s school trip to Israel, where he played ball for a number of pro teams starting in 2002 and served in the military. (He lives there with his family, running basketball clinics and business ventures like Aviv Net, a company that makes basketball nets that clean germs and sweat off the ball.) “There are certain things you don’t have to think very hard about, like, ‘Yes, this is squarely in our mission,’” said Ilana Ruskay-Kidd, Shefa’s founder and head of school.

This time around, in mid-December of 2024, with the launch of his book approaching, Goodman came to them.

Goodman and old friend Mike Sweetney, a former New York Knick, talk with Shefa’s boys’ and girls’ basketball teams. (Joseph Strauss)

His visit started with a brief tour of Shefa’s recently completed, $100 million building, during which he peeked into a class, shaking his head in amazement as students read and sounded out words one syllable at a time.

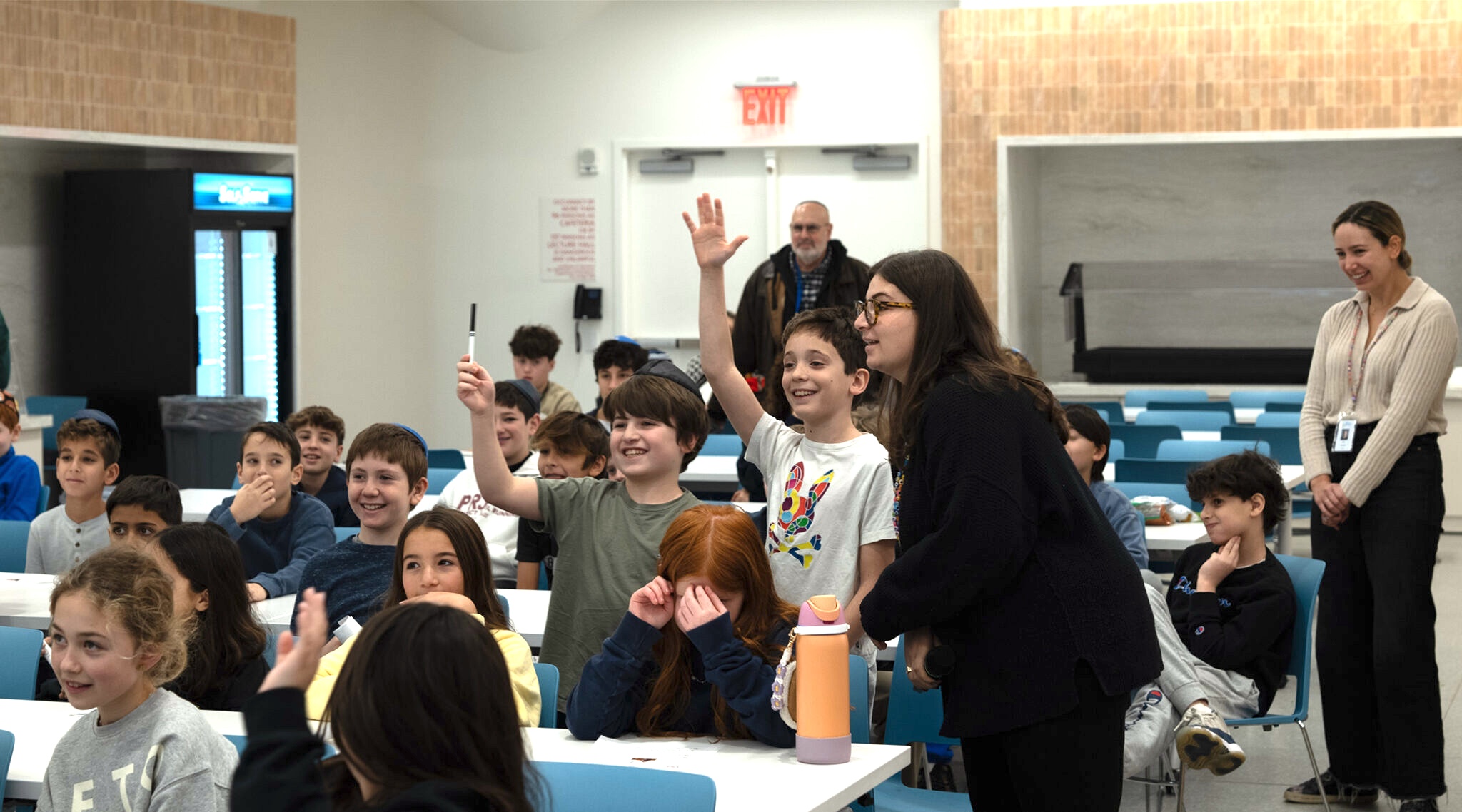

Then Goodman answered questions from a room of about 40 fifth-graders who’d read his book. The questions included everything from “Did you ever experience any antisemitism while you were playing?” to “Are you still friends with your teammates?” Goodman responded with an anecdote about his refusal to remove his kippah while an opposing college crowd taunted him for wearing one; after the game, he said, one of the fans gave him props for not relenting.

Following some group pictures and more autograph requests, Goodman hopped in the elevator to get to the gymnasium, where he and an old friend — the former New York Knick Mike Sweetney — held drills.

But as they prepared to return to class and carry on with their days, the fifth-grade students were left with a lasting message, summed up quite neatly by 10-year-old Allie: “I can play anything.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.