In a different world, Keith Siegel would have joined his siblings at their mother’s bedside as she breathed her last breath on Sunday.

Instead, Gladys Siegel, the family’s matriarch and a pillar of her local Jewish community, slipped away at 97 — unaware that her youngest son had been a hostage of Hamas for 421 days.

The family had shielded Gladys, who had dementia, from the horrifying reality, even as they devoted themselves to advocating for Keith and the rest of the Israeli hostages in Gaza.

“We are thankful that our mother did not have to suffer the pain and suffering of every day that Keith, her youngest child, her baby, has remained a hostage,” Lee Siegel, the oldest of Gladys’ four children, said during her funeral Tuesday at Beth El Synagogue in Durham, North Carolina, where I grew up.

Keith’s wife Aviva, released from captivity a year ago after 51 days, has met President Joe Biden, testified in the Knesset and spoken at rallies on multiple continents. This week, she was in North Carolina, part of the ingathering of the Siegel diaspora as Gladys stopped eating and began to fade.

In a eulogy, Aviva shared a detail from her time in captivity, recalling a moment two weeks into the ordeal when Keith broke the silence their captors had demanded.

“He came up to me and he whispered, and he said, ‘The first thing that I want to do when I get out of here is to go to my mom to give her a hug,’” she shared. “So Gladys, I’m here telling you that from Keith, because he would have loved being here, and it’s just unfair for him not to be here.”

Gladys Ruth Concors was born on July 11, 1927, in Brooklyn. After graduating from Syracuse University, she met and married Earl Siegel, a pediatrician who died in 2001 after more than 50 years of marriage. The couple lived in the San Francisco Bay Area before moving to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, in 1965, where Gladys became an enthusiastic and devoted booster of the local Jewish community and the Carolina Tar Heels.

In addition to making history as the first woman president of both the Conservative Beth El Synagogue and the Jewish Federation of Durham-Chapel Hill; heading the local chapter of Hadassah, the Jewish women’s organization; and steering Beth El’s 1987 centennial celebration, Gladys Siegel drew attention with her elegant nails — often painted in the signature blue of the University of North Carolina’s vaunted basketball team.

Gladys Siegel, her nails painted Carolina Blue, inscribes a pillar at Beth El Synagogue in Durham, North Carolina, during its renovation in 2018. (Jane Gabin)

During her funeral, Rabbi Daniel Greyber recalled where Gladys would sit each Shabbat, and where she would stand to share the names of any of her loved ones who were in need of healing during the Misheberach prayer for the sick.

“And when there was an injured Tar Heel basketball player, or when [Coach] Roy Williams was having knee surgery, she would proudly and wildly include their names, combining Gladys’ two religious life commitments, Judaism and Carolina basketball,” Greyber recalled.

Gladys Siegel’s generosity to her community was legendary, from the 50 years she spent delivering Meals on Wheels to her habit of visiting the sick to the weekly open-door policy she followed when it came to populating her Shabbat dinner table.

“I always used to talk to and ask her, how many people do you have on Friday for supper? And she said, I don’t know — yet,” Aviva Siegel recalled.

I was one of those guests one of the last times I saw Gladys, when I took my then-infant son to Chapel Hill, my hometown, to let my parents show him off to the community where I grew up. I have no memory of first learning that Gladys was an unparalleled pillar of that community, playing a role even in my very existence — as she sought to set up my mother, then her tenant, with my father more than four decades ago.

This week, I dug out my records from my 2010 wedding to confirm that, yes, Gladys was there, as she was at so many simchas. I also rediscovered something I had forgotten: that her gift to me and my husband was characteristic of her spirit: a donation to Mazon, the Jewish hunger relief organization.

“I don’t know if you guys know about the 50 years of Meals on Wheels that she did … I don’t think she needed to do more than that,” said her grandson Natan Siegel, who lived with his grandmother after moving from Israel to attend UNC.

For her children — Lee, David, Lucy and Keith — Gladys was an unflagging advocate — applying the same zeal, some of them recalled, to their Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts projects, their music lessons and their schoolwork as she did to her civic activities.

“She was solid, steady, supportive and interested in each of her children,” Lucy Siegel said, recalling that her mother turned their basement into a Girl Scout cookie distribution center each year. “She made time for each of us, individually and in connection with our activities.”

Gladys was active and involved well into her 90s. In her final years, she received frequent visits from her children; from her many friends; and from Greyber, who regularly posted selfies from her senior home.

There, her family took pains to ensure that she would never be aware of the tragedy that had befallen her son Keith, at his home in Kibbutz Kfar Aza, and her beloved Israel. Gladys Siegel is survived by four children, 10 grandchildren and 13 great-grandchildren.

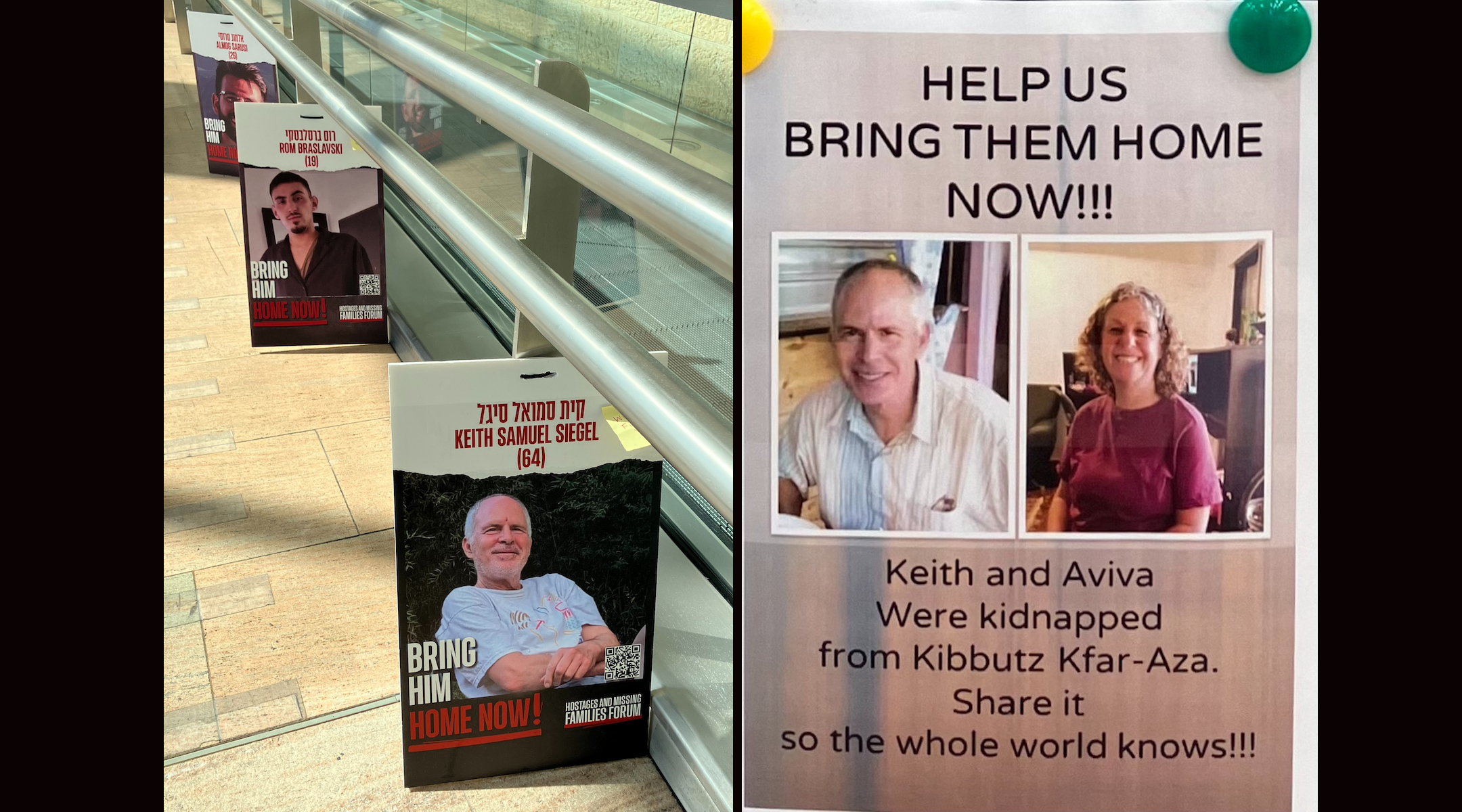

A hostage poster showing Keith Siegel can be seen at Israel’s Ben-Gurion Airport. His wife Aviva was freed from Gaza in November 2023. (Jane Gabin)

“Lucy, you were simply a hero, protecting your mom, keeping her from heartbreak, helping her to live out the last days of her life with chocolate in her mouth and peace in her heart,” Greyber said.

The rabbi said he had dreaded Gladys’ funeral, doubting that he could find the right words to match the woman who in many ways built the community he leads.

“I don’t know what a world looks like without my dear Gladys, I don’t know what the future holds for Keith, this precious family, or Israel, or our community. I don’t know, and if I’m honest, it’s pretty scary right now to try and imagine where the light is going to come from,” Greyber said.

“But Gladys taught us, ‘Maalin bakodesh,’ we go up in holiness,” he added. “We have to have the courage to light the candles ourselves, to bring more light into the world, to call and send emails of lovingkindness and connection, to march for hunger and bring and make home-cooked meals, to send hugs, and hugs and more hugs — now that Gladys’ light has gone.”

To that charge, Lee Siegel added another.

“We ask that the Beth El community honor our mother’s memory with renewed and urgent efforts to help us bring Keith and the other hostages home,” he said. “We must continue to believe that with hard work, a better day is coming — as that will always be our mother’s legacy.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.