Eighty-six years ago this week, a series of pogroms took place in Germany and Austria. More than 1,000 synagogues were burned, their pews destroyed; sacred Torah scrolls and holy books were set aflame. More than 7,000 Jewish businesses were ransacked and 30,000 men aged 16-60 were arrested and sent off to newly expanded German concentration camps. These pogroms were given a rather elegant name, Kristallnacht (The Night of Broken Glass), and it is by that name that they are best known.

Over the past 30 years the Germans have ceased to refer to the events as Kristallnacht but as the Reich Pogroms of November 1938. Crystal is beautiful, and has a certain sound and delicacy to it, but “Reich Pogroms” tell the much deeper truth of sanctioned violence against the Jews.

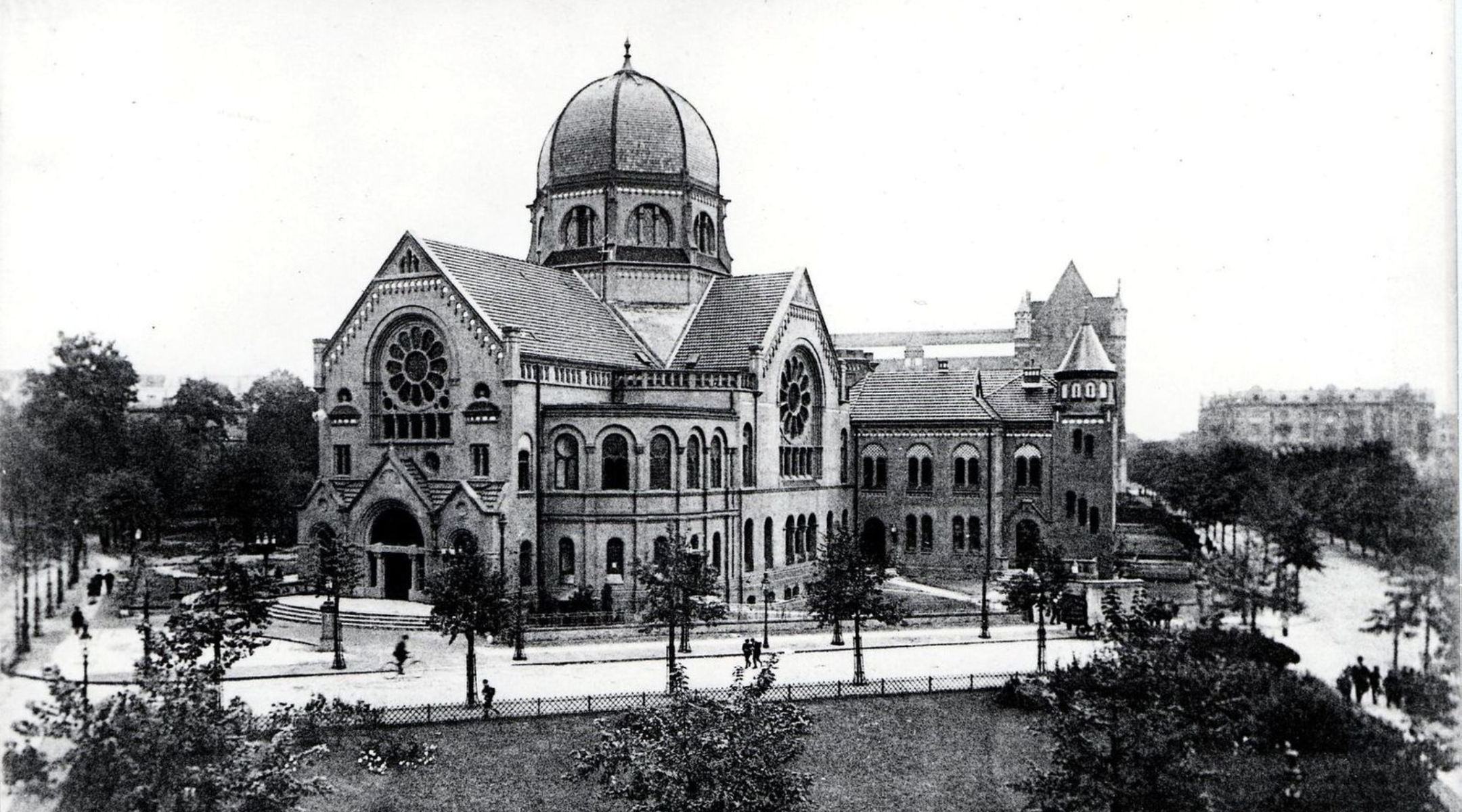

The synagogues that burned on those days were not just convenient targets for the Nazis and their allies; their attackers knew that they were a public manifestation of the role Jews had assumed in German society. Synagogues were often built in close proximity to Catholic cathedrals and protestant churches to indicate that Germany was a pluralistic, multi-religious community. Before World War II, there were 2,200 synagogues in Germany for 525,000 Jews. The synagogues were built as an expression of the great progress that the Jews had made within Germany, just as synagogues in the United States declared the prominent presence and public acceptance of American Jews.

What the Nazis did on Kristallnacht was to essentially show in the most physical, the most public way imaginable how far they were willing to go to tear the Jewish community out of the fabric of Germany.

The destruction of synagogues was also an act of grotesque political theater. Non-Jews brought their children to see the burning synagogues, just as white southerners in American brought children to lynchings and just as only three years later ordinary men and women in Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and in other former Soviet-occupied territories would bring their children to see the “Holocaust by Bullets,” the execution and burial in mass graves of Jewish neighbors and even friends.

Americans understood what the pogroms represented. By 1938, America had embodied the value of freedom of religion. No other event garnered such universal condemnation. From the extreme right to the extreme left, leadership in the Catholic, Protestant and every other form of religious denomination condemned Kristallnacht. If you are setting a synagogue up in smoke, they railed, you are destroying freedom of religion.

By attacking the synagogue, the Nazis were attacking not only the heart and soul of the Jewish community, but they were also attacking the institution that was responding to the unfolding catastrophe. Under Nazism and the imposition of increasingly stringent laws excluding Jews from institutions of everyday life, the synagogue became the replacement for those now-verboten institutions. On Monday it might become a theater because Jewish actors could not perform on the German stage. On Tuesday it became a symphony hall as Jewish musicians were dismissed from German orchestras. On Wednesday it became an opera house, because opera singers needed a place to earn a living.

During the day, the synagogue served as a school for Jewish children expelled from German schools. Their teachers were often professors, writers and artists struggling to survive in a new world. The art teacher might be a world class artist, the music instructor, a concert pianist. The Jewish school was the safest place for a Jewish child; yet the most dangerous part of the student’s day was walking to and from school. Harassment was routine, bullying was accepted, violence was sanctioned. Teachers turned their backs even when they did not overly encourage the violence.

Synagogues became the place for the distribution of welfare, and for classes teaching Jews mobile professions so they might earn a living in a new country. Synagogues were a training center for a generation en route to exile.

The synagogue was also a place where you taught people who didn’t know what it really was to be Jewish. The synagogue remained a place where prayers were recited, but prayers took on a new meaning.

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, the Jews in Germany were left without their synagogues. Many had lost their businesses and their homes. The concentration camps of Buchenwald, Dachau and Sachsenhausen were overflowing with new Jewish inmates. Most Jews were without illusions. Jewish life in the Reich was no longer possible. Many committed suicide. Most desperately tried to leave. Unwanted at home, Jews had only a few havens abroad. They could not stay and yet they had nowhere to go.

What are the implications for us of remembering the November 1938 pogroms in today’s post-Oct. 7 world, when synagogues and campus institutions like Hillel houses are targeted for supporting “Zionism”?

- The synagogue remains the most important symbol of the Jewish presence in a society.

- An attack on a synagogue is an attack on all of society.

- Synagogues must be secured not only by self-protection but by civil society that regards freedom of worship as an essential, indispensable component of a free society. The same is true for Hillel houses and other Jewish buildings.

- In Europe, synagogues have become seemingly armed camps, protected by the police and even the military. Sadly, we are already seeing that begin to happen in the United States. We cannot allow the situation to deteriorate any further.

- Civil society must hold. In the aftermath of the worst antisemitic killings in American history, the Tree of Life synagogue murders, civil society took control; political leaders, police officials, religious leaders and communal leaders all came together. The Pittsburgh Steelers and the Pittsburgh Penguins put Jewish stars on their uniforms, the World Series paused for a moment of silence, and the Pittsburgh Gazette printed the Kaddish on its front page. Haters cannot win, if those who do not hate join together to defeat them.

- Mayors and governors, police chiefs and district attorneys, moral leaders and community leaders must take the lead, and Jews must call upon their friends to step forward.

- Religious leaders must also step forward. Freedom of religion must mean freedom for all religions including Jews.

- If a swastika is painted on a Jewish building, priests, ministers, imams and all civil leaders must join hands with the rabbi in cleansing the building and jointly removing the stain.

- Jews must not be reluctant to exercise their power and must not allow our friends to become indifferent or complicit. We dare not accept this level of antisemitism as the “new normal.”

As we remember with pride the role of the synagogue and the prominence of the synagogue in German society, and the cruelty that was inflicted on Jews 86 years ago, we must resolve to end the explosive antisemitism we are experiencing today.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.