Brooklyn-based Jewish chef Jeremy Salamon cites three major influences in his life and in the kitchen: his mother, Robin; his maternal grandmother, Arlene; and his paternal grandmother, Agi.

While all three women were excellent chefs, only one is the namesake of his Hungarian-Jewish Crown Heights restaurant, Agi’s Counter.

Arlene was the grandma who showed Salamon how to truss and roast a chicken; mom Robin loved to gather loved ones and host elaborate Rosh Hashanah and Thanksgiving dinners. But it was Grandma Agi — a Hungarian Holocaust survivor who never spoke much about her past — who shared her love and her heritage through comfort foods like palacsinta, crepe-like pancakes that she stuffed with sugar and nuts.

Growing up, Salamon said that whenever he approached Agi to talk about the family or her past, “Her answer would be, ‘I’ll get the babka and coffee,’” Salamon recalled. “We’d eat our feelings.”

Salamon held onto these memories of Agi’s comfort food as he entered the stressful culinary industry and honored her memory when he opened Agi’s Counter in late 2021.

And while he always viewed her Hungarian Jewish cooking as a source of comfort — and inspiration — the chef admits that he worried how his concept would be received.

“Most people, when they hear Hungarian, if they have any idea the first thing that comes to mind is probably paprika or goulash — maybe chicken paprikás,” he told the New York Jewish Week. “The concept is so limited.”

As it turns out, his concerns were unwarranted. During its less than three years in existence, Agi’s Counter has emerged as an essential Brooklyn dining destination. In 2023, the restaurant garnered a Michelin “Bib Gourmand” award, as well as a spot on Bon Appetit’s Best Restaurants of 2022 list, where, they said, you’ll “feel like you’re being cared for by your very culinarily talented Jewish grandmother.”

Last summer, the New York Jewish Week also put Agi’s schmaltz potatoes, which are prepared confit-style in chicken fat, on our 25 Jewish Dishes to Eat in NYC list, and most recently, Salamon was a finalist for the James Beard Award for Best Chef in New York State (which ultimately went to Charlie Mitchell of Brooklyn Heights’ Clover Room).

“It’s wild, pretty crazy,” Salamon, 30, said of the accolades, talking with the New York Jewish Week on a rainy Monday afternoon between lunch and dinner service. “It is a complete shock in a really great way. Any attention really helps the restaurant and drives business and so we were thrilled to learn that.”

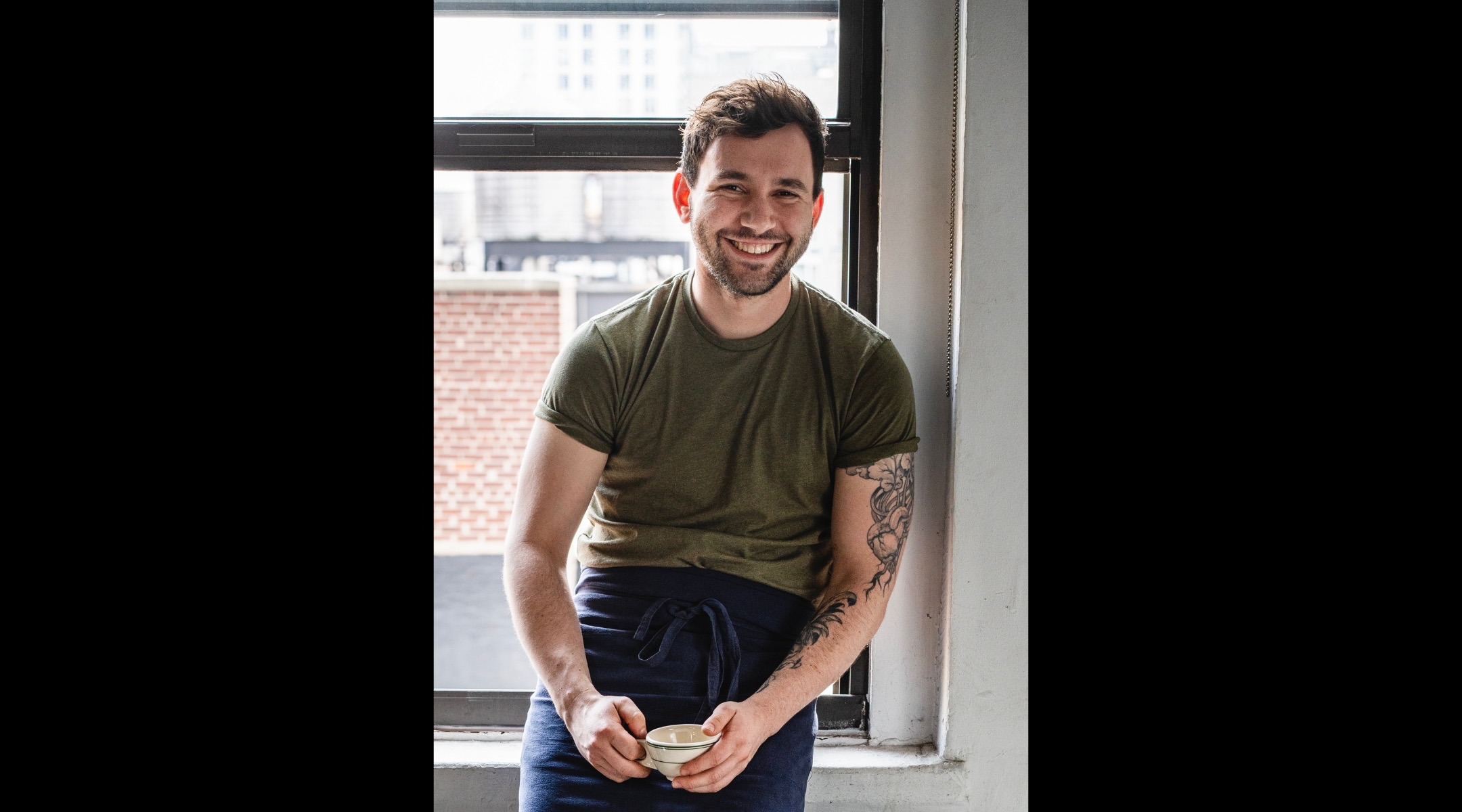

Salamon, 30, was a finalist for James Beard Award for Best Chef in New York State. (Marc Franklin)

The success of Agi’s Counter is particularly notable given that New York has historically had very little appetite for Hungarian food, said András Koerner, a historian of Hungarian Jewish food and the author of “Jewish Cuisine in Hungary: A Cultural History.” Koerner, who has lived in New York since the late 1960s, noted the city’s most famous restaurant serving Hungarian dishes, Cafe des Artistes, owned by Holocaust survivor George Lang, closed in 2009.

It is a “function of economics,” Koerner said. In the past, people were not willing to pay high prices to eat ethnic food that wasn’t Italian or French, he said.

“I feel like the dining scene in New York has drastically changed in the last eight or nine years,” Salamon said. “Obviously COVID reshaped everything. But there’s a different approach to dining these days, more of an open mentality — if I was doing this eight or nine years ago, it wouldn’t have resonated as much.”

Salamon grew up in Boca Raton, Florida, where he celebrated Jewish holidays like Rosh Hashanah and Hanukkah by gathering around the dining table with his family. “Food was always at the center of everything,” he said. “Growing up, I was lucky to have very big celebrations and holidays — eating and food and celebrating a holiday just felt like a really big deal.”

Salamon, who wanted to be a chef from the time he was 9, came to New York at age 18 to attend the Culinary Institute of America. A few years after graduating, Salamon became the head chef at The Eddy in the East Village and its sister restaurant Wallflower.Around this time Salamon picked up a copy of George Lang’s “The Cuisine of Hungary,” and connected with the recipes, remembering some from his childhood.

The palacsinta, a crepe-like Hungarian pancake, at Agi’s Counter. (Marc Franklin)

While working at The Eddy, Salamon said that he’d occasionally slip a Hungarian recipe onto the menu. Reactions were mixed, he said, but he believed in his vision — namely, to create a restaurant that was simultaneously homáge to his heritage and a way to provide his own take on Hungarian classics, reimagined for a 21st-century Brooklyn-based palate. In 2020 and 2021, he raised $65,000 to open Agi’s Counter through a grassroots Kickstarter campaign.

On the menu at Agi’s — a charming all-day cafe with a coffee-slash-wine bar and bakery case — there are plenty of dishes with paprika, as well as nokedli (a type of dumpling), borscht and an extensive list of Hungarian wines. But there are also offerings that Salamon has reinterpreted, like his pogacsa, a cheese biscuit that he serves with an egg and bacon, and his rotating versions of palacsinta, the crepe-like pancake, which he is currently serving with strawberry jam and caramelized chamomile honey.

Salamon readily admits that his food is not necessarily traditional. “Since we opened, there have definitely been many people that have come in here expecting it to be something from their fantasy, or thinking they’re going relive their childhood here, and they don’t — it’s not the experience they had hoped for,” Salamon said. “We’ve also had younger folks who are more open to it and say, ‘I get that it’s not authentic, it’s not traditional, but, at the core, I see what’s happening here.’”

Both responses, Salamon said, mean a lot to him — it shows that people in New York care about Hungarian food, and want to at least try his restaurant.

“People have different ideas of what constitutes Hungarian food and what constitutes Jewish food, but [Agi’s Counter] is certainly not, in a scholarly sense, traditional Hungarian food or traditional Jewish food,” said Koerner, who had not been to Agi’s but was familiar with the menu. “I don’t mean it as a criticism. It sounds very good and looks very appealing.”

Many of the dishes available at Agi’s Counter will be spotlighted in Salamon’s forthcoming cookbook, “Second Generation: Hungarian Jewish Classics Reimagined for the Modern Table,” which will be released in September from HarperCollins. In the cookbook, just like at his restaurant, Salamon takes inspiration from ancestral recipes and updates them as he sees fit.

“‘Second Generation’ is not my grandmothers’ cookbook, but it is my way of sharing a bit of their magic with you,” he writes in the introduction of the book, which he started working on before Agi’s opened. “Hungarian food is extraordinary, unique and full of old wisdom. I’m reimagining those traditions with an eye toward seasonality, market-driven ingredients, and a touch of millennial flair … because I want to help bring Hungarian cooking out of the shadows and into the twenty-first century.”

This summer, as Salamon focuses on launching the cookbook, he’s excited to bring seasonal menu items to Agi’s like stuffed squash blossoms, chilled borscht and sorrel soup, and to continue to develop it as a neighborhood comfort food and upscale dining restaurant all in one.

“In some ways, it just feels like the little restaurant that could,” Salamon said. “I’m very, very proud of everybody here.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.