(JTA) — As the 68th Eurovision Song Contest kicks into full gear, organizers who insist the event is “non-political” are fighting a crescendo of protests over Israel’s participation amid the ongoing war in Gaza.

The European Broadcasting Union, which organizes the global competition held in the Swedish city of Malmö this year, has tirelessly pushed one slogan: “United by Music.” But the group’s decision to keep Israel among 37 nations vying for a trophy has instead divided Malmö, triggered global petitions, caused artists to boycott and generated plans for a flood of street protests.

Eurovision launched with its first semifinal on Tuesday. Eden Golan, the 20-year-old singer representing Israel with her song “Hurricane,” drew both cheers and boos during a dress rehearsal on Wednesday in advance of the second semifinal on Thursday. Bookmakers have ranked Israel in the top 10 likely victors, which would land Golan among 26 contestants in the final on Saturday.

Locals in Malmö, which has a longstanding reputation for antisemitism and a record of attacks on Jews by both neo-Nazis and members of the substantial Muslim immigrant minority, unsuccessfully petitioned the city to bar Israel from competing. (The last time the city hosted the contest, in 2013, Jews and non-Jews held a rally after Israeli fans reported harassment.)

Now, Malmö is brimming with Swedish police, along with reinforcements from Denmark and Norway, ahead of demonstrations against Israel’s participation, including a boat march that took place on Wednesday. Police expect more than 20,000 protesters in the small city’s streets, outnumbering about 15,000 people holding tickets to gather in the Malmö Arena. Outside of Malmö, Eurovision is expected to draw more than 150 million people to TV screens worldwide.

Participants hold up banners during a demonstration outside the City Hall in Malmö, Sweden on April 10, 2024 in connection with the municipal board’s consideration of a citizens’ proposal to stop Israel’s participation in the Eurovision Song Contest. (Johan Nilsson/TT News Agency/AFP via Getty Images)

Israel’s inclusion in the contest sparked international backlash because of its deadly military campaign in Gaza. More than 160,000 people have signed a petition to ban Israel from Eurovision, while 20 artists dropped out from performing in events surrounding the contest. Some protest groups have organized alternative events in Malmö, such as “FalastinVision,” billed as a “genocide-free song contest” hosting 15 artists from eight countries — including the Palestinian territories — at a live show scheduled for the same time as Eurovision’s final.

Among the artists performing at FalastinVision is Bashar Murad, a Palestinian singer who competed to represent Iceland in Eurovision this year and lost to Hera Björk.

“Palestine is blocked from major events around the world — including Eurovision — so it’s difficult for Palestinian artists to showcase our culture and art globally,” Murad said in a statement to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “FalastinVision is a beautiful way to address that.”

Boycotters have accused Eurovision of a double standard for including Israel after excluding Russia from its contest in 2022 after Russian troops invaded Ukraine. Noel Curran, head of the EBU, has maintained that Russia was cut off for failing to meet broadcaster guidelines that Israel has met.

“Comparisons between wars and conflicts are complex and difficult and, as a non-political media organization, not ours to make,” Curran said in a statement. “In the case of Russia, the Russian broadcasters themselves were suspended from the EBU due to their persistent breaches of membership obligations and the violation of public service values.”

For many Israelis, the country’s participation and success in the contest is a point of pride and an antidote to concerns — heightened this year amid the war — that Israel is isolated on the world stage. Israel was accepted into the contest in 1957, its second year, causing Egypt and Syria to exit. It competed for the first time in 1973 and has since won four times, most recently for “Toy” by Netta in 2018.

As part of Eurovision’s “non-political” guidelines, the contest bars flags and signs other than the national flags of participants and the rainbow pride flag — which means that Palestinian flags are not allowed in the venue.

On Tuesday, opening act performer Eric Saade — a former Swedish contestant of Palestinian origin — wore a keffiyeh, a scarf seen as symbolizing Palestinian solidarity, on his wrist. Saade was reprimanded by the EBU, which said in a statement, “We regret that Eric Saade chose to compromise the non-political nature of the event.”

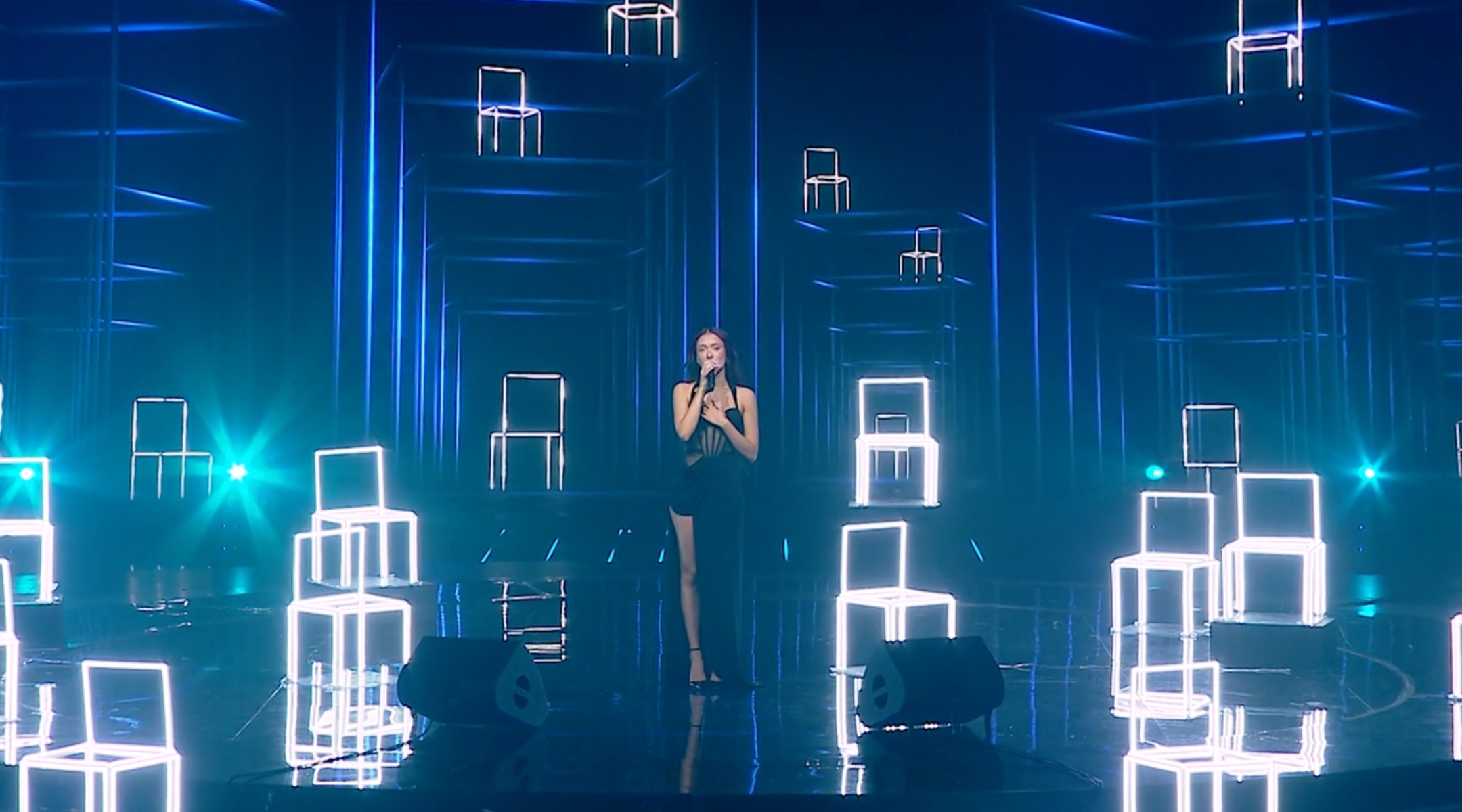

Eden Golan performs an emotional rendition of Aerosmith’s “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing,” surrounded by empty chairs representing the missing hostages, for her grand finale performance to represent Israel in the 2024 Eurovision Song Contest. (Screenshot via Mako.co.il)

The EBU also cited politicization concerns as its reason for rejecting Golan’s initial song entry, titled “October Rain.” The song appeared to reference Hamas’s Oct. 7 attacks on Israel, which killed about 1,200 people, took some 250 hostage and triggered Israel’s military assault in Gaza. Golan tweaked the song and renamed it “Hurricane,” although its lyrics and video could still be interpreted as a reaction to Oct. 7.

Golan is largely staying out of view during Eurovision week for fear of security threats, skipping most events other than the live shows and rehearsals, and is being accompanied by a security detail. In lieu of the contest’s opening “turquoise carpet” event on Sunday, she went to a local ceremony marking Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Fredrik Sieradzki, who heads the Jewish Learning Center in Malmö, said he welcomed Golan together with the Israeli delegation. Malmö is home to a small Jewish community of about 1,000 people, including some parents who have complained of antisemitic incidents at their children’s schools since Oct. 7, according to Sieradzki.

“Eden Golan lit one of the candles. We lit six candles and the seventh one, of course, for the latest victims,” Sieradzki told JTA, referring to the people killed on Oct. 7. “It was a very emotional get-together, we felt we were family. When Jews come here, we welcome them.”

In an interview with Reuters, Golan avoided criticizing the protests against her performance.

“It’s up to the people what to do,” she said. “They have the right to speak their voice, but I’m focusing on my part which is giving the best performance, and on the good, on the good vibes, the good people.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.