(New York Jewish Week) — Darya Arad grew up looking at photo albums of Kibbutz Nahal Oz, a small, idyllic community where her mother, the Israeli author Maya Arad, lived for a time during her childhood.

There were pictures of elementary school children, of multi-generational families, of Purim celebrations and weddings held throughout the 1970 and ’80s at the kibbutz located in southern Israel, near the Gaza border. And though Darya Arad herself grew up in the Bay Area, she felt she knew Kibbutz Nahal Oz intimately — along with hearing stories about what life was like there, she visited with her family.

So on the morning of Oct. 7, 2023, when Hamas militants invaded southern Israel, taking more than 1,200 lives and more than 250 hostages — including murdering nearly 75 people from Nahal Oz — it felt personal to Arad, an 19-year-old art student at Cooper Union in New York City. She immediately picked up her paintbrush and started painting.

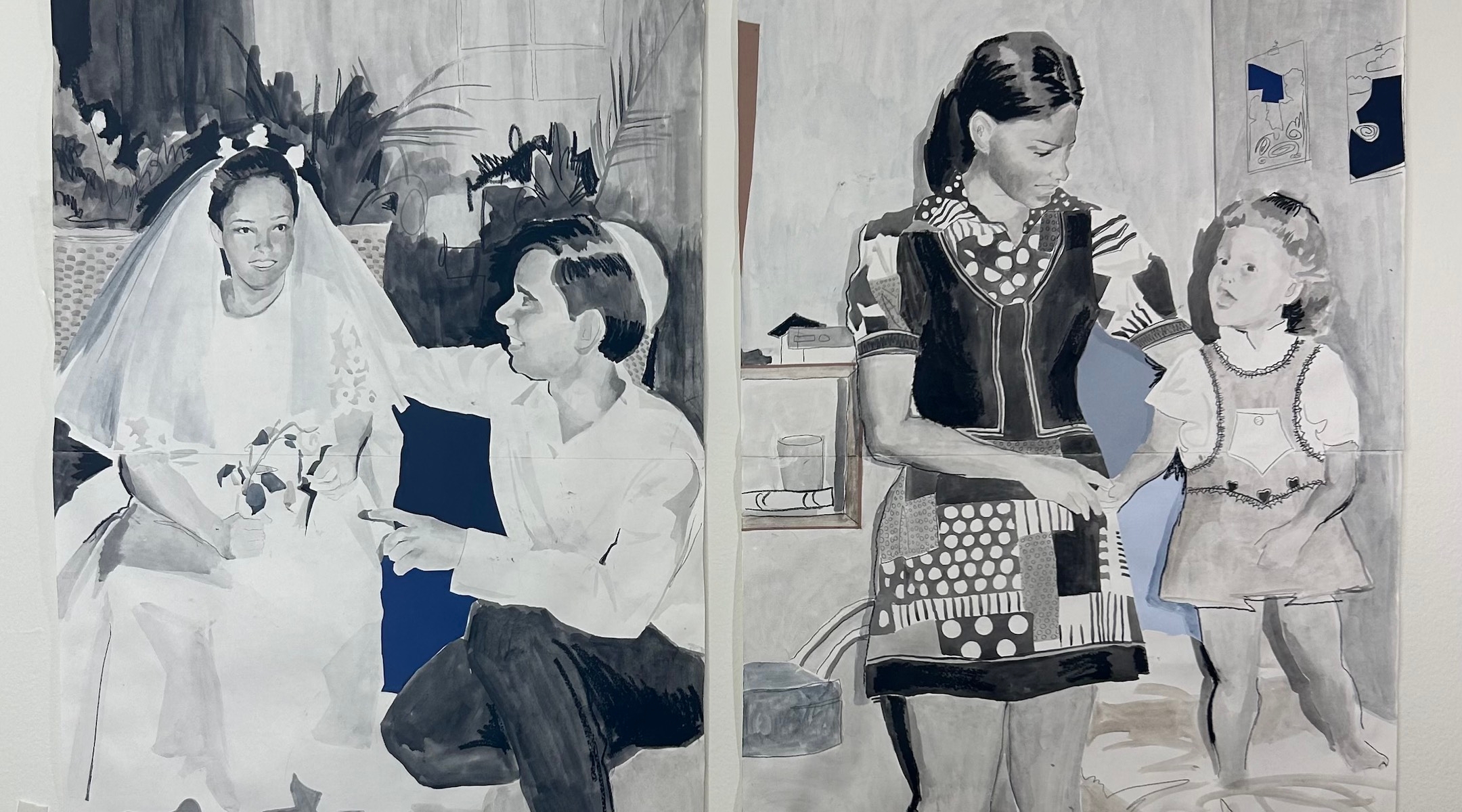

“Independence Day celebration, 1975.” (Courtesy Darya Arad)

The 18 paintings she created, some two-by-three feet and some three-by-four feet, all based upon her mother’s photographs, will be on exhibit at the downtown university this week — Arad’s first solo show at the school. “Kibbutz Nahal Oz,” will be on view March 12 through 16 in the seventh-floor lobby at Cooper Union’s Foundation Building (7 East 7th St.), the same Astor Place building that houses the university’s library, where, as seen in a viral video from Oct. 25, a group of Jewish students were barricaded inside, seeking refuge from pro-Palestinian demonstrators.

“After the [Oct. 7] attack, it felt very odd to look at these photos as they were — just in color and sitting in these albums,” Arad told the New York Jewish Week. “I painted one and then it just continued and continued.”

Describing her output over the past five months, “I kind of went insane, just painting all the time,” she added.

Arad said she wanted to create work based on her Israeli identity, as a way of pushing back against anti-Israel voices on campus and in the art world.

“In the art world, in recent years, there’s been a lot of focus on figurative art and figurative art that has to do with issues of identity. This is probably the most popular form of art on the market right now — art about gender or race or ethnicity or sexuality,” Arad said. “So it’s very interesting to me that in this environment, there’s suddenly now a push towards discrediting and diminishing [Israeli and Jewish] identity.”

“The reason I’m doing this is to create work in this format that’s accepted — making work about one’s identity, but about an identity that is hated, and sometimes not even hated — sometimes just people refuse to acknowledge it exists,” she added. “In a way, every painting is just proof — you can’t say [Israeli identity] does not exist, because every painting says ‘here I am.’”

While the photographs of her mother’s childhood were captured in full color, Arad made her paintings in just three muted tones of black, brown and blue. “In the Israeli artistic canon, there is a strong visual language of kibbutz life: small, colorful pictures that belong solely in the modest world of illustration,” Arad writes in her artist statement about her exhibit. “Kibbutz life cannot be depicted in its previous postcard size. Cannot be portrayed in the sunlit colors of its past.”

“The grandmothers of the Kibbutz making matzoh balls for the communal Seder, 1979, based on a photo by Moshe Gross.” (Courtesy Darya Arad)

The works represent the first time Arad created work about her Israeli identity. “It felt like something for the moment,” she said.

Arad emphasized that her paintings are not meant as hasbara, the Hebrew term for public diplomacy. “In this moment and the way things are, it feels to me that there is something interesting and dynamic that I can do with my Israeli identity through art,” she said. “I care first and foremost about creating a work of art that I feel is strong.”

University campuses across New York have become hotbeds of activism in the months since the Israel-Hamas war began, with some demonstrations turning violent: At Columbia University uptown, for example, just a few days after Oct. 7, a 19-year-old reportedly attacked an Israeli student. On Oct. 25, the same day Cooper Union Jewish students were locked inside the library, a Washington Square Park rally near New York University featured a demonstrator holding an antisemitic sign reading, “Please keep the world clean,” with a figure placing a Star of David in a trash bin.

Blood splatters on the floor of a family’s home in Nahal Oz in the immediate aftermath of the Hamas attacks on Oct. 7, when some 75 people in the southern Israeli community were killed. (Kobi Gideon/GPO)

Cooper Union did not respond to multiple requests for comment about the exhibit, though Arad pointed out the university’s Foundation Building has a security guard at the entrance.

“All universities have kind of become hotspots for anti Israeli bigotry and antisemitism — it does feel kind of tense to put up,” she said, adding that other Cooper Union students have displayed work on campus about the Israel-Hamas war from a Pro-Palestine perspective. “I’ve had a lot of students say, ‘Oh, I’m scared for you,’ but I don’t know if anyone’s planning anything.”

“I think it feels like the calm before the storm,” she added.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.