(JTA) — On Thursday afternoon, hundreds of marchers gathered on New York’s East Side, waving signs reading “Dump AIPAC” and carrying posters with the names and faces of lawmakers who had accepted donations from the pro-Israel lobbying group.

The protest, which passed the Manhattan offices of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, was organized by the anti-Zionist group Jewish Voice for Peace, which says AIPAC is obstructing an Israel-Hamas ceasefire resolution in Congress.

“On top of buying our senators’ and congressmen’s silence, AIPAC has also been silencing the only brave politicians who have been standing up for Gaza and have been standing and calling for a ceasefire,” declared one of the speakers, a young woman wearing a “Not in My Name” sweatshirt.

Since the Oct. 7 massacre of Israelis by Hamas and the deadly war in Gaza that followed, JVP has led protests against the war at Grand Central Terminal, the Statue of Liberty, the U.S. Capitol and the Manhattan Bridge, earning the group headlines and foll0wers. But none of those protests captured the generational and ideological divisions within the Jewish community quite like Thursday’s rally. It represented a clash between the premier representative of the mainstream pro-Israel consensus among Jews and an upstart group representing Jews who have lost, or never had, faith not just in Israel’s government but in the very idea of a Jewish nation-state.

It’s not exactly an even split: While JVP’s visibility and membership have grown since Oct. 7, surveys, philanthropy and anecdotal evidence suggest most American Jews remain supportive of Israel and the war on an enemy sworn to its destruction.

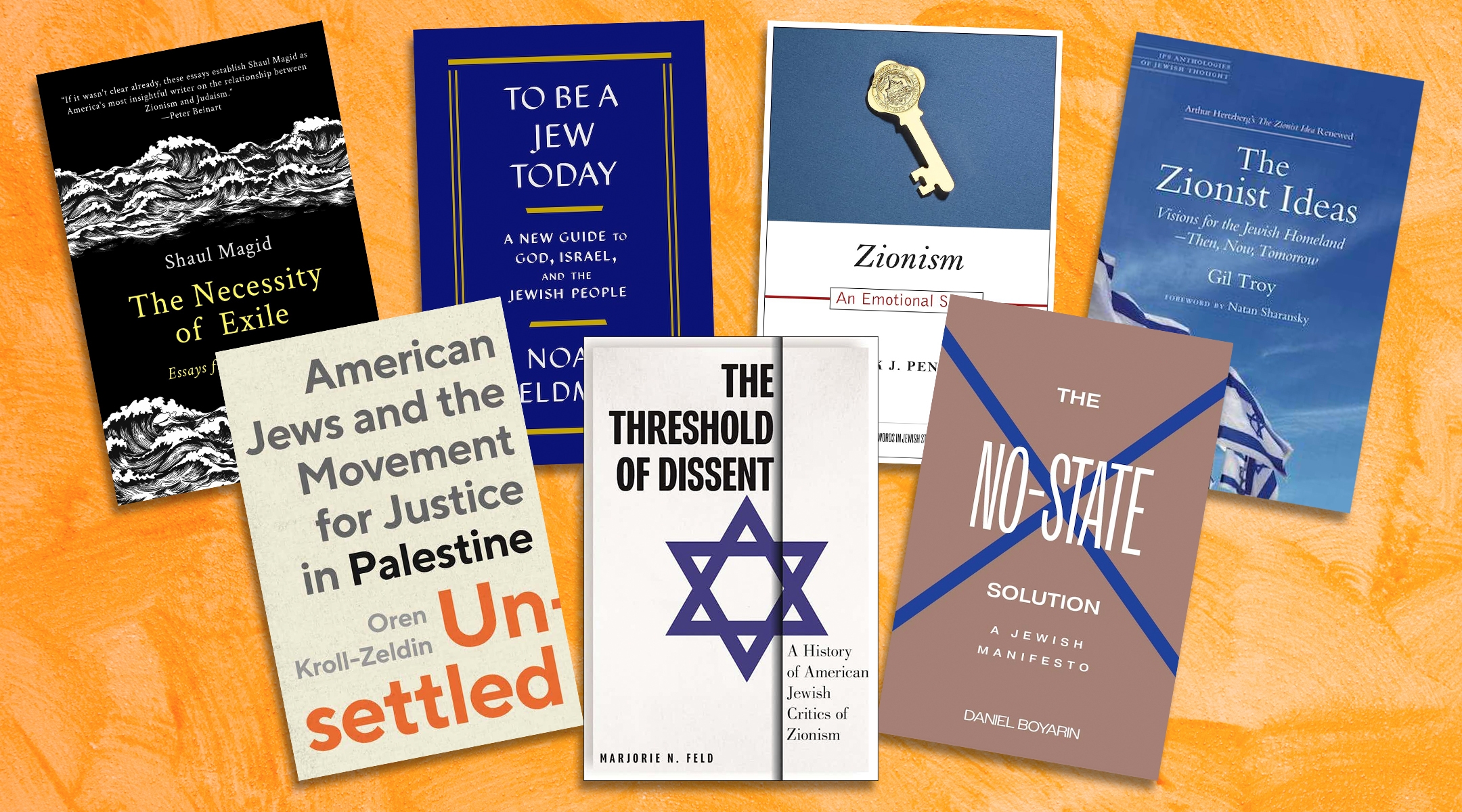

But according to a spate of new books that were in the works before the war, JVP and other anti-Zionist and non-Zionist groups reflect trends that have been building for several years among the Jewish majority that considers itself liberal: discontent among younger Jews who have no memories of Israel’s founding, no hope for a resolution to the conflict and no faith in an Israeli government that has only shifted further to the right in recent years. The Oct. 7 debacle and the grinding war in Gaza, following a year of protests over the course of the country’s’ democracy, have added oxygen to their criticism.

“Today, progressive American Jews increasingly find it difficult to see Israel as a genuine liberal democracy, mostly because some three million Palestinians in the West Bank live under Israeli authority with no realistic prospect of liberal rights,” writes Noah Feldman, the Harvard University law professor and first amendment scholar, in his new book, “To Be a Jew Today.”

Pro-Palestinian Jewish American demonstrators rally outside the Manhattan headquarters of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee and the offices of Senators Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand, Feb. 22, 2024. (Selcuk Acar/Anadolu via Getty Images)

A guide to Judaism in the tradition of Herman Wouk’s “This Is My God” and Anita Diament’s “Living a Jewish Life,” Feldman’s book convincingly explains why anti-Zionists get under the skin of of the Zionist majority, for whom “three-quarters of a century after the state’s creation, Israel has become a defining component of Jewishness itself.” (The italics are his.)

That explains, he writes, why anti-Zionism feels like antisemitism to many Jews. “If you feel that Jewishness is or should be fundamentally linked to Israel, then when someone says Israel should not exist, the criticism impugns the core of your Jewish identity and belief. It rejects who you are as a Jew. It rejects the content of your Jewish commitment and identity you have based on it,” he writes.

These emotional components of Zionism are often overlooked in the never-ending debate about Israel’s founding and perceived sins, writes Derek Penslar, a professor of Jewish history at Harvard, in his book “Zionism: An Emotional State.”

Penslar’s book came out last year but got back in the news after he was appointed co-chair of a Harvard task force on antisemitism. Critics cherry-picked a passage from the book to suggest that he thinks Zionism draws on a hateful strain within Judaism.

In fact, the book is about all of the emotions that animate Zionism, which he defines as “the belief that Jews constitute a nation that has a right and need to pursue collective self-determination within historic Palestine.” Those emotions include pride, solidarity, religious piety, fear, self-preservation and, yes, occasional hatred for the “other” who made Jews miserable for centuries.

Like Feldman, Penslar describes why American Jews became so emotionally attached to Israel, even if they had no intention of moving there: “It was a place where Jews need never apologize for their identity, where Hebrew was literally shouted in the street, where a Jew would almost inevitably marry another Jew, and where assimilation in the Western sense was impossible. In these respects, the love of Israel was an aspiration of self-preservation.”

It follows, then, that “if in your view the only legitimate expression of Zionism is Jewish sovereignty and hegemony within the Land of Israel, then someone who opposes Israel as a Jewish state is ipso facto an antisemite.”

The new Jewish anti-Zionists deny this, with many saying they want an alternative state in Israel-Palestine that preserves the security and dignity of both Jews and Palestinians. (The word “safety” comes up a lot in their writing.)

Shaul Magid, a professor of modern Jewish studies at Dartmouth College who this year is a visiting professor at Harvard, has given up on the idea that Israel as a Jewish nation-state can be a true liberal democracy. “In my view the Zionist narrative, even in its more liberal forms, cultivates an exclusivity and proprietary ethos that too easily slides into ethnonational chauvinism,“ he writes in his book of essays, “The Necessity of Exile.”

He is not against a State of Israel, but writes, “I am not in favor of it functioning as an exclusively ‘Jewish’ state.” He imagines an “alternative scenario” in which Jews and Palestinians, including those currently living in Gaza and the West Bank, have equal rights in a bi-national homeland.

For many Zionists, this sounds a bit like the Woody Allen joke: “And the lion will lie down with the lamb, but the lamb won’t get much sleep.” Magid acknowledges his vision is utopian and leaves the details to others, but says his project is the opposite of antisemitism: He wants to recover the idea that Diaspora, or exile, has been good for the Jews and may in fact be their truest, most humanistic expression, while assuring that Israel will be “a more liberal and more democratic place for the next phase of its existence.” (He’s not the only proponent of what Philip Roth once called “diasporism” and young Jewish activists are calling doikayt [Yiddish for “hereness”]: In his new book “The No-State Solution,” the Talmud scholar and “active anti-Zionist” Daniel Boyarin asserts that “the Jews are a diaspora nation” without the need of what is “on the way to being a racist, fascist state.”)

Magid, 65, came of age in the 1960s and ‘70s, and he describes an evolution from Conservative Jewish suburban kid to countercultural seeker who for a time embraced haredi Orthodox Judaism before becoming a scholar of religion and Judaism. The books that crossed my desk tend to be written by Jews 40 and older. (Geoffrey Levin, the author of the new book “Our Palestine Question,” is 32, but his book is about American Jewish criticism of Israel from the 1940s through the 1970s, not the experience of today’s activists.)

David Ben Gurion, who was to become Israel’s first prime minister, reads the Declaration of Independence May 14, 1948 in Tel Aviv, during the ceremony founding the State of Israel. A portrait of Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern political Zionism, appears on the curtain behind him. (Photo by Zoltan Kluger/GPO via Getty Images)

In his forthcoming book “Unsettled: American Jews and the Movement for Justice in Palestine,” Oren Kroll-Zeldin, 43, interviews younger activists from four main pro-Palestinian Jewish groups — IfNotNow, the Center for Jewish Nonviolence, All That’s Left and JVP.

Describing himself as “an embedded participant in the movement,” he calls his own process of disillusionment with Israel “unlearning Zionism.” Raised in a Reform Jewish family in Los Angeles — his grandfather, Rabbi Isaiah Zeldin, founded L.A.’s Stephen S. Wise Temple; his mother, Rabbi Leah Kroll, was among the first group of women rabbis ordained by the Reform movement — Kroll-Zeldin attended Jewish day school and summer camps and visited Israel as both a participant and staff on free Birthright trips. As a young adult he came to the conclusion that “Jewish liberation in Israel was predicated on the oppression and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians.”

“Jews who unlearn Zionism not only contest widely held narratives about the ‘righteous’ nature of Israel’s national project but also reject a monolithic pro-Israel identity,” writes Kroll-Zeldin, assistant director of the Swig Program in Jewish Studies and Social Justice at the University of San Francisco.

He also challenges criticism from some mainstream groups that the young non- and anti-Zionists lack a sense of Jewish “peoplehood” or solidarity. “This new generation of Israel engagement through Palestinian solidarity activism is based on a love for and a commitment to the Jewish people,” he writes.

“Critics of anti-Zionism dismiss them as naive, as misguided, as self-hating Jews, perhaps as antisemitic themselves. And that couldn’t be more divorced from reality,” Kroll-Zeldin told me in an interview. He said groups like JVP and IfNotNow are “creating Jewish organizations and Jewish spaces” and using Jewish language and ritual in their activism.

The activists he studied, he continued, approach their activism from a standpoint of Jewish “safety,” telling him that “our safety cannot happen on the backs of other people. If other people are being oppressed, that does not guarantee our safety. Quite the opposite.”

Kroll-Zeldin also rejects what he calls a “Zionist consensus” among American Jews that says Jewish safety is guaranteed by a “supremacist state with a strong military.”

“What we actually see is that that has not protected Jews,” he said. “In fact, the worst calamity to happen to the Jewish people [since the Holocaust] happened [on Oct. 7], ironically, in the very place that was created to prevent that type of catastrophic attack on Jewish life.”

Jewish anti-Zionists regularly remind critics that there have always been Jews opposed to Zionism, including haredi Orthodox Jews who opposed a secular Jewish state in the Holy Land on religious grounds, and Bundist Jews — East European revolutionaries influenced by Marxism — who wanted to be part of a global socialist society. Before 1948, establishment groups like the American Jewish Committee and the Reform movement worried that a Jewish state would raise the specter of “dual loyalty,” and resented the claim by many Zionists that a Jewish state represented the “negation of the Diaspora” (in Hebrew, “shlilat hagalut”) and that authentic Jewishness could only be lived in Israel.

Much of that opposition faded or was sidelined after the Holocaust and Israel’s founding in 1948, when even Jews with a universalist bent saw the dire need for a country that would take in the remnants of Europe’s decimated Jewish community and, shortly thereafter, the Mizrahi Jews tossed out of Muslim countries. Following the Six-Day War of 1967 especially, American Jews tended to fully embrace Israel, variously as an expression of religious fulfillment, a source of cultural possibility, a just-in-case haven or as an embattled sibling demanding their protection and support.

Bundist leaders at a Poland-wide gathering, Warsaw, 1928; (left to right) Yisroel Lichtenstein, Yitskhok Rafes, Henryk Erlich, Yekusiel Portnoy and Bella Shapiro. At left is a portrait of Bundist leader Vladimir Medem, who died in 1923. The Yiddish banner reads: “Bund in Poland. Proletarians from all lands unite!” (Ch. Bojm/Wikimedia Commons)

Despite this consensus, every generation since has had dissenters, as Marjorie N. Feld shows in her forthcoming book, “The Threshold of Dissent: A History of American Jewish Critics of Zionism.”

The book is a history of American anti-, non- and disillusioned Zionists from the Reform movement in the early 20th century to the pro-peace groups of the 1980s. The “threshold of dissent” is her term for the limits placed on internal Jewish debate by “American Jewish Zionist leaders,” who ended up “marginalizing progressive American Jews who were able to see Palestinian suffering.“

As a result, she writes, “these leaders narrowed conversations about Jewish belonging. Their unwillingness to see these ideas as uncontested and subject to debate has been, in no small part, responsible for the growing generational divide among American Jews.”

Feld, 52, a professor of history at Babson College in Massachusetts, wrote in 2016 that after a “very Jewish upbringing” during which she learned “that only Israel” could prevent another Holocaust, she no longer considers herself Zionist, having concluded that “that Israel fit neatly into my broader understanding of Western colonialism.”

Her decision cost her friendships among colleagues and in the wider Jewish community. “It’s very difficult for them to think of me as within the threshold of Jewishness anymore, because I have left behind this thing that has been important to them all their lives,” she told me in an interview.

But she rejects some of the common charges made against Israel’s critics by the pro-Israel mainstream, including the narrative, as she writes in her book, that “American Jewish critics of Zionism and Israel historically have cared little for the American and global Jewish communities and the future viability of these communities.”

“I’ve been to Israel, not for a long time, but I certainly don’t want it to fall into the sea,” she said. “I certainly don’t want the safety of anybody compromised there. But I don’t think Zionism as it’s expressed in the current leadership of Israel is making or maintaining security and safety.”

Similarly, Feld said the Jewish anti-Zionists who join in pro-Palestinian chants of “from the river to sea” are not calling for the destruction of Israel. Rather, they no longer believe a two-state solution is viable, and instead think about anti-Zionism “as a means to make [Israel and Palestine] a safer place for all people, not just us.”

Critics of anti-Zionism, however, find these kinds of distinctions specious, one-sided and divorced from a reality in which 7 million Jews are living in a sovereign country and aren’t going anywhere. In 2003, the late feminist and cultural critic Ellen Willis wrote disapprovingly that the anti-Zionist left “does not oppose nationalism as such, but rather defines the conflict as bad imperial nationalism versus the good liberationist kind.” A left that reduces “all global conflict to Western imperialism versus third World anti-imperialism,” she wrote, ignores “a considerably more complicated reality.”

Willis’ essay is excerpted in “The Zionist Ideas,” a 2018 anthology edited by Gil Troy, a McGill University historian who is now a senior fellow in Zionist thought at the Jewish People Policy Institute in Jerusalem. The book is an update of sorts to “The Zionist Idea,” the late Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg’s classic anthology of Zionist writings.

Troy, who was familiar with some of the new books, is troubled not only by what he sees as a double standard applied to Jewish nationalism — why the left vilifies Jewish nationalism but lionizes Palestinian nationalism — but also by the tendency to focus on Zionism as an abstraction versus Israel as a complicated reality. The result, he says, is an ideology that ignores how ethnonationalism is the raison d’être of dozens of other countries whose legitimacy is rarely called into question, and that assigns no Palestinian responsibility or agency for the moribund peace process.

“Let’s just apply the same analysis to Palestinian nationalism, to the Muslim countries, to Australia, to France, and let’s see where Israel comes out in the mix,” Troy said in an interview. “But the obsessive singling out of Israel and of Zionism and using historical mistakes and sins against the pure ideology is jumping back and forth between pragmatic and theoretical. It’s throwing out any kind of intellectual consistency to make a debating point.”

And as an American-Israeli with children currently serving in the Israeli military, he is critical of the uncomfortable American college student who decides, “’Well, if the cost of having Israel is not having a two-state solution, and the cost of having Israel is all this suffering in Gaza, then maybe we don’t need an Israel.’ It’s very comfortable for you to say that from 6,000 miles away. It’s very comfortable for you to kind of cancel a country because it doesn’t work for you.”

In “To Be a Jew Today,” Noah Feldman writes that “turning one’s back on Israel in favor of a Jewish life focused exclusively on the Diaspora is … not theologically viable”; meanwhile, he emphasizes “the simple fact that Israeli exists, is real, and is home to half the world’s Jews. It is not going away anytime soon.”

But he also acknowledges the dilemmas facing the Jewish left, and expresses them in theological terms. “For Progressive Jews,” he writes, “the struggle now and in the foreseeable future is to see if divinely inspired social justice can be reconciled with the real Israel — and, if not, to see what aspects of Jewish belief and practice might convince the next generation of Progressives not to give up on Jewishness altogether.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.