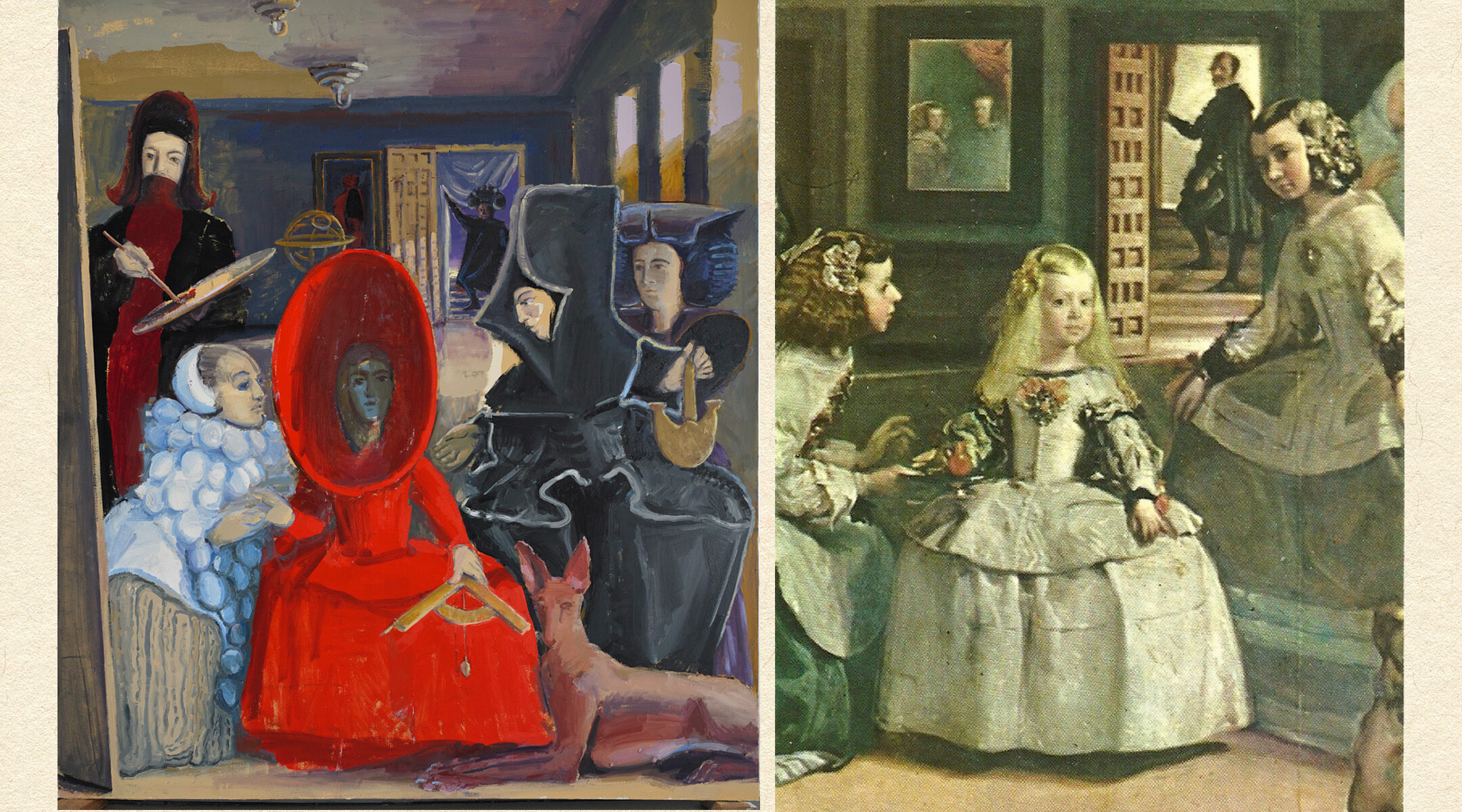

(New York Jewish Week) — At first glance, Tirtzah Bassel’s painting of a young woman surrounded by her three attendants and a portraitist seems familiar.

That’s by design. Bassel’s work, “La Menarquia” (“The Menarche”), is a study of Diego Velazquez’s renowned 17th-century group portrait “La Meninas” (“The Ladies in Waiting”). But, despite mirroring Velzaquez’s composition — including costumes that reflect Spanish court attire of the time — Bassel’s version is radically different. Velazquez’s painting depicts an infant princess whose position in life is dictated by more powerful men; in Bassel’s version, meanwhile, the princess is at the center of an imagined ritual in which she comes into her menarcheal blood power as a woman.

“La Menarquia” is just one of a series of paintings by Bassel that turns the tropes of classic “Western” art on its head. Bassel’s solo exhibit at the Slag Gallery in Chelsea, “Canon in Drag,” features 35 pieces that, as a collection, create an imaginary world outside the patriarchy — one in which women’s experiences are centered.

“What if the firsthand experience of birth was part of the main story, not a footnote?” Bassel asked rhetorically. “What would that canon look like?”

Bassel, 43, told the New York Jewish Week that her approach to these paintings have been inextricably molded by the Jewish experience. “I feel like all of Jewish history is cycles of subversion and canonization,” she said. And now she’s painting a new one.

Though she now lives and works in Brooklyn, Bassel grew up in an Orthodox family in Jerusalem. She views her childhood as a mixed bag: While it was culturally rich, she also sensed that, as a woman, she’d never reach the highest places of power. “When I went to midrasha [an institute of Torah study for women], I specifically went to one where I could study Talmud, because it was clear to me that in order to hold the keys to power in that world, that was one thing you had to have,” she said.

While that gender inequity was a major factor in Bassel’s eventual departure from Orthodox Judaism as a young adult, she said she still maintained an affinity for canons (Jewish or otherwise) and the belief that she could out-maneuver the patriarchy if she worked hard enough.

By age 22, halfway out the door of the Orthodox world and on track to become a social worker, Bassel stumbled upon a drawing class at the Jerusalem Studio School. The institution’s atelier-style approach to art education appealed to Bassel’s respect for tradition, and she quit studying social work to enroll full time in the Studio School. Since the program wasn’t accredited, the choice to be there, she felt, was the highest form of commitment to the arts: learning art for its own sake, or art “lishma” in Hebrew.

The Studio School’s dual emphasis on painting from daily life and learning from the masters inspired Bassel and helped shape her artistic career. At the same time, however, Bassel felt the institution — along with the wider art world — reinforced the gender biases that she thought she’d left behind with Orthodoxy. “The art world in general is incredibly misogynist — though sometimes it’s not immediately visible,” she said.

For example, Bassel, who has two children under 7, said she’s heard motherhood described as “career-ending” by many people in the scene, from artists to dealers to collectors. “I really think it’s true across the board in the art world that the image of the ‘capital-A artist’ is a bohemian man,” Bassel said, “someone who rebels against society and lives an alternative life and is more of a catalyst than a stable, responsive person. Motherhood is perceived as the opposite of that.”

Bassel’s “Orgasmic Birth of Mrs. Arnolfini,” left, is a response to Jan Van Eyck’s 15th-century “Arnolfini Portrait.” (Barry Rosenthal/ courtesy of the artist and Slag Gallery and Lluís Ribes Mateu/Flickr)

Bassel believes she internalized these sentiments to the extent that she sheltered her first pregnancy from public view. “I was really determined that nothing was going to change,” she said. “I’m having my baby over here in my private life, and I’m doing my artwork over here. Being pregnant and going to an opening really felt like outing myself.”

However, the birth of a second child, a daughter, which happened just before COVID-19 hit, changed everything. “When my daughter was born, [the compartmentalization] started feeling even more insane,” she said. “I started making these drawings and paintings of the birth experience, and it hit me: There are no pictures of birth in the Western art canon.”

Throughout the long months of lockdown, Bassel’s identity as mother and artist were forcibly melded. She couldn’t go to her studio to paint; between taking care of her kids and working her day job at a nonprofit she had little bandwidth left for art, anyway. Lacking both time or space to work in her traditional medium, oil paints, she began to use a fast-drying, water-based paint called gouache.

“It felt a little like the end of the world — my studio was gone, the future of galleries was unclear,” Bassel said. “Everything was up in the air and that liberated me. Then something clicked, and it was almost like a joke at first. I thought: ‘What would canon look like if this firsthand experience of birth was part of the main story, not the footnote?’”

She tried “flipping” a few iconic works and posted the images on Instagram. In her take of Jan van Eyck’s 15th-century “Arnolfini Portrait,” for example, the pregnant wife is now in the midst of a realistically rendered orgasmic birth. The response was immediate: “There was an outpouring — folks telling me that I was sharing things that were so personal to their lives, that they’d never seen depicted before.”

Sometimes, though, her flips were flops. Simply replacing female nudes with male nudes didn’t always work; after all, there are already many male nudes in the canon (think: Michelangelo’s “David”). By contrast, portraying fathers erotically performing skin-to-skin contact, the way that nursing mothers are often depicted in classical art, felt very subversive.

These artistic experiments eventually became the “Canon in Drag” collection — the 35 gouache paintings on display at the gallery, plus some additional works still in progress.

Though not a fan of labels — the term “Jewish artist” makes her squirm as much as “woman artist” — Bassel admits that her public grappling with Western art canon, while, at the same time, respecting canon enough to wrestle with it, stems from her Orthodox Jewish background.

“It’s a blueprint for what I’m doing right now,” she said. “Despite the rigidity of Orthodox life, I experienced the parshanut [exegesis] model as very creative and full of agency for the individual. Many people could interpret the same text differently and take it into their lives in different ways. Canon is a technology for having a really rich conversation that simultaneously goes back in time and into the future.”

These days, Bassel identifies as a secular Jew but that has not stopped her continued engagement with Jewish culture and text. But she’s still figuring out how, or if, these elements will play into her future work.

After all, when Bassel began the paintings that became “Canon in Drag,” she said she couldn’t imagine that images of childbirth would appeal to a universal audience — but she’s since realized that this, too, was an internalized bias. “Who is your ‘universal’ is exactly the key question,” she said. “The canon has an assumption about that, and that’s exactly what ‘Canon in Drag’ is challenging.”

“Canon in Drag,” is on view at Slag Gallery, 522 West 19th Street, October 27th through December 3rd, 2022.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.