(JTA) – Marvin Chomsky often relayed one searing memory from the set of his 1978 miniseries “Holocaust.”

While shooting sequences in Austria to dramatize the mass murders of Jews both at Nazi concentration camps and in the Babyn Yar ravine outside Kyiv, Ukraine, Chomsky recalled how a young camera operator had challenged the narrative of what they were filming.

“Mr. Marvin, you are making this up for the movie,” the cameraman said, as Chomsky recalled in a video remembrance of his career for the Director’s Guild of America. “This didn’t really happen.”

So Chomsky turned to a nearby German crew member. “Is it true or not true?” he asked.

“And all eyes went right to him, and he thought and he said, ‘Ja, das ist war,’” German for “Yes, that’s true,” Chomsky recalled. “All the kids, the young ones, just ran off crying their hearts out, they didn’t believe it. And I didn’t say another word.”

Thanks to Chomsky, who died March 28 in Santa Rosa, California, at the age of 92, “Holocaust” showed millions of people — including around 20 million Germans — that the Holocaust did indeed happen.

When it aired in the United States and West Germany, the four-part miniseries attracted upwards of 120 million viewers and helped spark broad public dialogue around the causes and consequences of the genocide of European Jews. Many Germans called into their TV stations in tears to express their shame at the events depicted onscreen, and some former Nazi soldiers were even moved to confess details of their crimes.

Frank Bösch, a German historian, told the BBC that he believes the miniseries’ broadcast on German TV in 1979 ranked alongside the Iranian Revolution and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s election as one of the key events of that year that transformed the world.

The first major dramatization of the Holocaust produced for a mass audience in the English-speaking world, the miniseries starred Meryl Streep and James Woods and tracked the lives of two fictional families in Nazi-occupied Germany, one Jewish, the second Christians who eventually become Nazis. Covering a vast range of real-life Holocaust events, including Kristallnacht, the Warsaw Ghetto uprising and the concentration camps of Buchenwald, Auschwitz and Sobibor, the series was a revelation for many. It was the subject of controversy, as well: Survivor Elie Wiesel contended that the series trivialized its namesake atrocity.

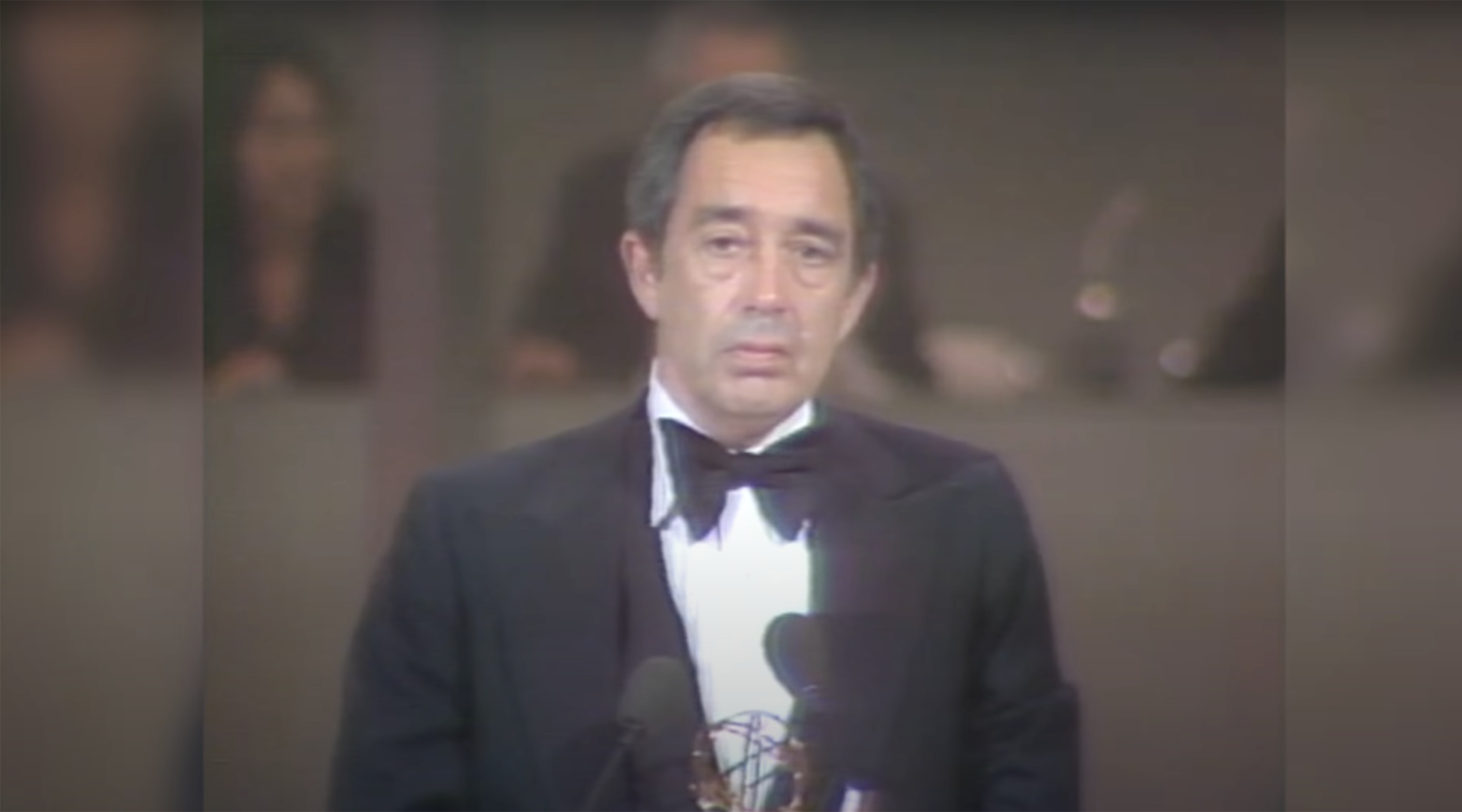

Chomsky helmed all of it (from a script by Gerald Green), an experience that his son Eric said left him “traumatized.” He won an Emmy for it, one of four he earned in his career. Intuitively, he sensed that turning the monumental tragedy of the Holocaust into a simple family story would make it easier for the general public to grasp. “I said, ‘I’m not doing a documentary. It’s not even a docudrama. It is going to be a drama about people and if you care about the people, you will watch it,’” he said in the Director’s Guild interview.

The Bronx-born son of Jewish parents who immigrated from Belarus, Chomsky started his career in TV while still in high school. After college and his Army service, he began working as an art director and set designer for shows including “Captain Kangaroo,” transitioning to directing in the early 1960s.

In addition to “Holocaust,” Chomsky also had directing roles on many other monumental TV projects. He directed two episodes of “Roots,” the landmark 1977 miniseries delving into American slavery of Black people, and also helmed installments of the socially progressive sci-fi series “Star Trek.”

He directed a few other Jewish-themed projects as well, including “Victory at Entebbe,” a TV movie about Operation Entebbe, and “Inside the Third Reich,” a 1982 TV movie based on the memoir by Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect (the making of which was recently chronicled in a controversial Israeli documentary that did not mention Chomsky’s involvement).

But “Holocaust” was where Chomsky made his biggest mark on the culture — and it’s a mark that will not soon be forgotten. In 2019, German TV reaired the series to mark its 40th anniversary.

“Survivors came to the Auschwitz trials and journalists didn’t even interview them,” Bösch recalled. “No one cared about the victims. That changed with ‘Holocaust.’”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.