Even when it comes to restitution for the living, somebody has to speak for the dead. The dead cannot make monetary claims, yet they have the right to assert moral ones – on all of us.

Throughout these recent restitution initiatives, there has been a lot of acrimony about money, but very little focus on dignity, which is a hallmark of social justice. The precedent that the Swiss bank case creates, the impression it leaves, the memory it honors, in many respects is as important as the money it distributes.

The court’s allocation formula contemplates distributing 75 percent of the recovered looted assets to Nazi victims who now live in Russia based on an indiscriminate finding of overall need. Meanwhile, the court plans to allocate only 4 percent of the money to Holocaust survivors living in the United States based on a presumption that the American survivor community is either more affluent or can seek charitable assistance elsewhere.

But there are, conservatively estimated, a minimum of 30,000 Holocaust survivors in the U.S. living under the poverty line, and nearly half of these people have no access to social services. In what meaningfully material way are these people less destitute than the victims of the former Soviet Union?

The U.S. and Russia each have roughly 18 percent of the worldwide population of Nazi victims living within their borders (with roughly 46 percent living in Israel). Yet when it comes to a narrower definition of Holocaust survivors – the way such a designation is more conventionally understood, not as mere targets of Nazism, but rather those who were either in concentration camps, ghettos or subject to slave labor – the moral basis for such a lopsided windfall to Russia loses all moral currency.

Of the Holocaust survivors worldwide who were interned in concentration or slave labor camps, or who were in ghettos, an estimated 28 percent live in North America, while 13 percent reside in both the FSU and in all of Eastern Europe. (The number for Israel is about 50 percent).

Under what moral grounds, and legal criteria, is it proper to favor one community of Nazi victims over another when the American and Israeli survivors comprise the cast majority of former concentration camp inmates?

There is a long history in art, culture, politics, and even law that Holocaust survivors – those who witnessed the Nazi horrors, those who survived the concentration camps – automatically obtain a priveleged position whenever it comes to matters pertaining to Nazi genocide. They cannot, as a matter of basic moral justice and decency, be deprived of legal standing to speak – in any forum or tribunal – about the horrors they witnessed. And similarly, they should not be deprived of money that derives from their losses, particularly if they have needs that are being unmet elsewhere.

These people are iconic figures; indeed, they have become metaphors for mas murder. The Nazis gave them special, forbidden knowledge. They observed firsthand inhumanity at its most barbaric and extreme. It is their unspoken testimony that sets them apart from the rest of us – even from the rest of all other Holocaust survivors. It is what makes them entitled to everything we can do, and anything they wish to say.

The Jews of the FSU are not, as the Brooklyn Federal Court continues to proclaim, the double victims of Nazism, which now justifies them, presumably, to double relief. The Nazis had no agenda for Jews other than mass death. They would never have contemplated life in the Soviet Union as a sufficient punishment for the Jews of Europe. The Final Solution was not about hardship but annihilation. Such a twisted formulation of comparitive suffering is an indignity to those who witnessed the Nazis in action. What happened at Auschwitz was imcomparable. Being a casualty of communism is in no way the same thing as having survived the camps.

Yet there is no question that those Jews who feld Eastern Europe and avoided the camps altogether eventually found themselves caught on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain. They left behind a great deal – people and possessions they could never reclaim. And after the war they suffered enormously, and they have continued to suffer economically in the ravaged evolution of the post-Soviet society. But the cruelties and deprivations of communism are, legal and morally, not the subject of these restitution proceedings.

And frankly, while it is true that many of these Russian Jews experienced terrible hardships after the Holocaust, they were fortunate to be in the Soviet Union during the Holocaust. They showed great instincts, fortitude and courage in venturing east, but such sacrifices ultimately saved their lives.

Surely Holocaust victims who survived the worst of the Nazi murder machine, and have present economic or medical needs – regardless of where they now live – are entitled to receive restitution funds. Excluding survivors with such genocidal pedigrees is an affront not only to the living, but also a desecration to the memory of the dead. It is the blanket and indiscriminate favoritism I oppose because in the concentration camp universe, all men and women were equal in the eyes of the murderers. Why are hey not at least equal in the eyes of this court?

Indeed, this court seems to be saying that the very people who are entitled to restitution – given what they witnessed, given what they survived, given what they lost – should look instead to Jewish institutions for charity, while those who properly should seek charity instead are to receive restitution from money that in all probability is not even traceable to their losses.

It is morally unconscionable for those whose needs are great, who witnessed the worst and who are now suffering from the consequences of what they saw to be disallowed from receiving their fair share of these restitution proceeds simply because they were liberated from the concentration camps and did not end up in the Soviet Union.

Restitution is not the same as charity. Restitution is legally and morally very specific. You receive it for what happened to you, and what you lost, at the time the injury occurred.

The court likes to focus on the fact that American survivors have thus far received 29 percent of the settlement proceeds. Therefore, they shouldn’t complain that they are now going to be grossly shortchanged in receiving restitution for looted assets. But these American recoveries derive from bank accounts and slave labor claims. We should take no pride in returning money back to the people woh once owned it, or in finally paying workers for their slave labor.

Why should a desperate Holocaust survivor be deemed ineligible to receive restitution simply because someone else had a Swiss bank account and finally got his money back?

Similarly, the fact that Holocaust survivors worldwide have received $50 billion over the past 50 years from the German government in reparations payments is equally irrelevant to this discussion. These are pension payments for suffering, and have nothing to do with restitution for looted assets. And given the high percentage of concentration camp victims who ended up in Israel and America, they were certainly deserving of reparations for their suffering.

Finally, many survivors, on moral grounds, chose not to accept such payments. Why then should these people now be prevented from recovering looted assets from the Swiss simply because they had once declined to take any money from the Germans?

Clearly we all deplore dog-eat-dog dimensions of these proceedings. But let us not trivialize and desecrate the memory of those who died in the most ghastly and extraordinary of ways by equating it with postwar sufferings. The legacy of the Swiss bank case should not be remembered as having allowed destitute Holocaust survivors – regardless of present geography – to die on this court’s watch with numbers still on their arms. The concentration camps were a uniquel different, more ferocious strain of inhumanity. The dead demand that we do not mix metaphors. Let us focus on the Nazi atrocity and not on the perils of a far less evil empire.

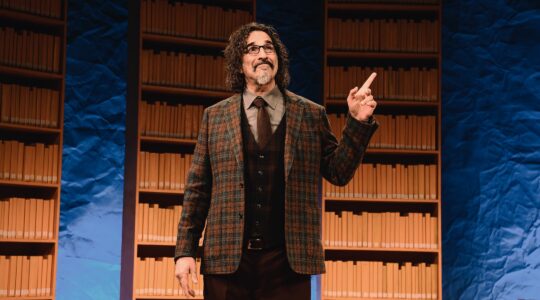

Thane Rosenbaum, a novelist and law professor, is the author of "The Myth of Moral Justice: Why Our Legal System Fails to Do What‘s Right." This essay is adapted from remarks originally addressed to Judge Edward Korman at last week’s hearing in Brooklyn Federal Court.

|

Signup for our weekly email newsletter here. Check out the Jewish Week’s Facebook page and become a fan! And follow the Jewish Week on Twitter: start here. |

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.