Every woman who is disappointed about Elizabeth Warren’s withdrawal from the primaries can empathize with the feeling that our contributions and competencies are not fully valued. This isn’t about endorsing a candidate, rather it is about the reinforced pained feeling that no matter how many credentials we have – in Warren’s case not just a law professor as Barack Obama was, but a celebrated Harvard Law professor, and multi-term United States senator and crusader on behalf of consumers – women remain underappreciated and not as fully recognized as some men with fewer qualifications. It’s a trend we’ve lived all our lives where men who are less talented or creative or smart are time and again promoted over women.

Megan Garber wrote in the Atlantic about Warren being punished for her competence, quoting feminist philosopher Kate Manne of Cornell speaking of misogyny, “It is perhaps that mechanism at play when a woman says, “I believe in us,” and is accused of being “self-righteous.” So perhaps the antidote to misogyny then, is to believe in us as women, our abilities and our competence and that we need not be apologetic for either. I was so moved to hear the episode of Talking Talmud on Berakhot 63 when Yardeana Osband spoke about feeling listened to, knowing people care what she has to say. I am glad to be among the listeners who believe that what women teach has value. I am hopeful that every time a woman is listened to it can remove 1/60 of the sting of misogyny, a measure we will hear about when we get to Nedarim 39a/b regarding the pain of the sick being removed by a get well visit.

I was so moved to hear the episode of Talking Talmud on Berakhot 63 when Yardeana Osband spoke about feeling listened to, knowing people care what she has to say. I am glad to be among the listeners who believe that what women teach has value. I am hopeful that every time a woman is listened to it can remove 1/60 of the sting of misogyny, a measure we will hear about when we get to Nedarim 39a/b regarding the pain of the sick being removed by a get well visit.

Women are more than used to being overlooked and ignored. So how can reading an ancient text written by men help us as women with beliefs about ourselves and our abilities that in some ways diverge from views of the world we cherish?

From my study of Berakhot for the past 63 days, I would say that even when there are things that are objectionable, the overall sense of the Talmud is that women have intense personalities. I loved that Yalta in Berakhot 51b breaks four hundred barrels of wine in a rage to show that she would not stand to be disrespected – and gave the man ignoring her a zinger of a curse that “from itinerant peddlers come meaningless words and from rags come lice.” This story, which I had not known before, shows women at full humanity allowing them to express rage at being overlooked.

Women can teach kindness as Bruriah does on Berakhot 10a when she instructs her husband how to pray, “ Rather, pray for God to have mercy on them, that they should repent” instead of asking for their death. The fact that it is a woman who teaches mercy, the Hebrew word “rahamim” emanating from the Hebrew for “womb,” “rehem” is not accidental. It is a quality women are able to access and communicate to others.

One of my favorite sections of Berakhot concerns a mother and her deceased daughter on Berakhot 18b. The topic of discussion is whether the dead know what is happening in the world of the living. To prove this, the dead daughter requests that her mother send her a care package via so-and-so who will be the next to die. For me, as a mother of three daughters constantly requisitioning needed items from me, it feels so familiar and real to have a daughter signaling to her mother that she is adjusting to life in her new place by asking for a care package of a comb and blue eyeshadow. I believe the story is an attempt to comfort the bereaved mother by reassuring her both that her child still needs her and that a core part of her daughter still lives and that her essential personality is intact and has remained in the transition to the next world.

But the thing I found most important to learn from Berakhot was not the stories of women as fully human, both in intense rage, powerful empathy and being comforted in a bereaved state. It is the attitude the rabbis posit of believing oneself to have agency no matter the situation.

But the thing I found most important to learn from Berakhot was not the stories of women as fully human, both in intense rage, powerful empathy and being comforted in a bereaved state. It is the attitude the rabbis posit of believing oneself to have agency no matter the situation. It is expressed most powerfully on Berakhot 61b by Rabbi Akiva as he is dying, his skin being flayed by Roman combs of iron, yet he prolongs his pronunciation of the “one” in the “Eternalis One” of the Shma prayer. In response, a bat kol, a heavenly voice cries out, “Happy are you Rabbi Akiva that your soul left your body on the word ‘one’.” The fact that there is joy associated with the tragedy of martyrdom is extraordinary. Rabbi Akiva could not choose how to die; he could choose how to react to the suffering he was experiencing.

There are so many more women involved in learning of all kinds in this cycle of daf yomi, and the more women feel that they are competent at understanding a body of knowledge and discussing it with others, the more we will believe in our own agency.

This is a lesson valuable to all of us, women and men both, to feel that we have the ability to choose how to react to a situation, to have agency.

Yes, we still live in a world where a female candidate who is prepared and has plans for everything cannot get the chance she deserves to wield power to create better conditions for all. But we can choose to continue to work and organize for a world where people want to listen to women. And for me, learning Talmud from women and valuing their insights has been a wonderful boon to my sense of change being made in the world even if it has not yet permeated all levels of our society. There are so many more women involved in learning of all kinds in this cycle of daf yomi, and the more women feel that they are competent at understanding a body of knowledge and discussing it with others, the more we will believe in our own agency. And the more we behave as though we have some agency, even in overwhelming situations, the more we can actually affect the world to be more like Bruria and create conditions where mercy is extended to us all.

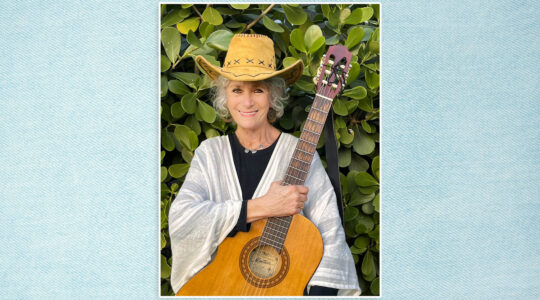

Beth Kissileff is author of the novel Questioning Return and editor of the anthology Reading Genesis: Beginnings. She wrote on the parsha last year for 929 and is at work on a book about coping with trauma, based on events in her Pittsburgh community. Visit her online at www.bethkissileff.com.

Posts are contributed by third parties. The opinions and facts in them are presented solely by the authors and JOFA assumes no responsibility for them.

If you’re interested in writing for JOFA’s blog contact dani@jofa.org. For more about JOFA like us on Facebook or visit our website.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.