My Facebook feed is filled with altruistic friends and relatives going above and beyond to help those less fortunate during the Covid-19 crisis. One spent all weekend in her basement sewing masks. Another organized a community effort to make face shields to donate to first responders. Many are organizing chesed programs, volunteering for food drives, and, sadly, setting up shiva visiting hours over Zoom. Their kids are supermarket shopping for seniors, launching fundraisers, leading kumzits concerts, and tutoring for free.

While I’m inspired by these myriad acts of kindness, they haven’t motivated me to do more than provide cheerful comments and a thumbs up to those who are doing them. Instead, I’ve found myself sinking into a state of coronavirus guilt that hits me in the pit of my stomach usually when I’m indulging in a long hot shower.

I could be doing more. I should be doing more. But my guilt is overridden by my strong desire to practice Debussy on the piano or go for a 5-mile run with my daughter. I’m relishing the short spurts of free time I have when I’m not working, cooking, or spraying down my countertops.

So why do I feel so guilty for not doing more to save humanity? Do my feelings stem from my upbringing — both culturally and religiously? Do other women feel this way? Do men?

“I’ve done literally nothing, and I just don’t want to,” a friend of mine (another Jewish woman) told me. “My kids console me when I feel bad about it. Mom, you can’t rise to every occasion. Covid19 just isn’t your thing.”

As it turns out, coronavirus guilt is a “common reaction” to Covid19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guilt can take many forms: Feeling bad if someone is bringing food or other necessities while you’re staying isolated; feeling guilt around not being able to perform normal work or parenting duties; guilt felt by responders experiencing secondary traumatic stress reactions.

As it turns out, coronavirus guilt is a “common reaction” to Covid19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guilt can take many forms: Feeling bad if someone is bringing food or other necessities while you’re staying isolated; feeling guilt around not being able to perform normal work or parenting duties; guilt felt by responders experiencing secondary traumatic stress reactions.

“Between the ideal of who you should be and the reality of who you are, lies guilt,” writes journalist Ruth Andrew Ellenson in the essay compilation The Modern Jewish Girl’s Guide to Guilt. She notes that she hears a voice in her head as an internal reprimand worried that she’s going to make one false move and screw everything up for the Jewish people. “The guilt works its way down my chest and hooks my heart… whenever I’ve flat out failed to live up to the prodigious expectations of my people.”

While Ellenson wasn’t writing about coronavirus guilt in particular, the same feelings apply. In fact, coronavirus guilt may be even more complicated, much like the structure of the virus itself with its crown-like spikes. While I may not have felt too guilty about disinviting my out-of-town Passover guests (as my state law dictated), I did feel guilty about appreciating the lower levels of stress I felt before the holiday, knowing that I wouldn’t have a houseful of company.

In fact, coronavirus guilt may be even more complicated, much like the structure of the virus itself with its crown-like spikes. While I may not have felt too guilty about disinviting my out-of-town Passover guests (as my state law dictated), I did feel guilty about appreciating the lower levels of stress I felt before the holiday, knowing that I wouldn’t have a houseful of company.

As restrictions begin to loosen a bit in the coming weeks, we will be facing difficult and likely guilt-ridden decisions on how to start socializing again. When can we start inviting friends over again for Shabbat meals? Can we plan a summer wedding for 150 if there are no longer state restrictions? Should we disinvite the grandparents? Is it right to put the other guests at risk with the virus still circulating?

Taking such risks can lead to the worst kind of coronavirus guilt: the kind that stems from knowing that you may have unwittingly spread the virus to others.

An ER doctor infected with Covid-19 wrote on this blog for Elemental last month, “I feel guilty because I’m horrified that I may have exposed other people to Covid-19. I was at a conference out of town a few days before getting sick.” Others have to deal with having potentially infected their coworkers, at worst, or having forced them into a two-week quarantine, at the very least.

Stemming from this is perhaps the worst kind of guilt: “survivor’s guilt”. It’s when people feel like they have done something wrong by surviving a traumatic event, like Covid-19, when others have not, according to Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatrist Neha Chaudhary in an interview with ABC News. Those who survived when their loved ones have died from the virus may have the toughest time dealing with these feelings.

As coronavirus guilt stems from multiple causes, learning to manage these feelings will depend on their root cause. My guilt was a bit assuaged when I learned others couldn’t bring themselves to volunteer for a coronavirus cause. I also remain committed to cheering for those around me who are doing amazing things, and I have stepped up my efforts to reach out to friends and family who are struggling in isolation.

We can’t lock ourselves indoors or physically distance from friends and family forever — nor should we. We can, however, use whatever guilt we’re feeling now to motivate us to adopt smarter health habits that make us more socially responsible human beings in the future.

If there’s any lesson to be learned from this guilt, it should be that we have a collective responsibility to do our best to avoid transmitting infections to others. We should stay home from work when we’re feverish, coughing hard, or sick with a stomach bug. We should make sure everyone in the family is up to date on immunizations. (The measles outbreaks last year seem like forever ago, but they were a direct result of under-vaccination.)

And how many of us missed our annual flu shot last year? Fewer than half of Americans regularly get this vaccine, but I’m betting this percentage will rise as we ponder the implications of infecting others with a potentially deadly respiratory disease. We can’t lock ourselves indoors or physically distance from friends and family forever — nor should we. We can, however, use whatever guilt we’re feeling now to motivate us to adopt smarter health habits that make us more socially responsible human beings in the future.

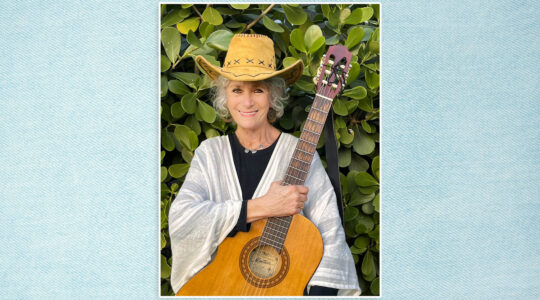

Deborah Kotz is a former journalist and freelance writer from Silver Spring, MD.

Posts are contributed by third parties. The opinions and facts in them are presented solely by the authors and JOFA assumes no responsibility for them.

If you’re interested in writing for JOFA’s blog contact dani@jofa.org. For more about JOFA like us on Facebook or visit our website.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.