(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — Photographer Emile Bocian grew up the son of Polish Jewish immigrants in New York. But when he died in 1990 at 78, he left an unlikely legacy as a chronicler of Manhattan’s bustling Chinatown.

A photographer by hobby, if not vocation, Bocian took some 80,000 to 100,000 photographs of the densely populated Lower Manhattan neighborhood throughout the 1970s and 80s, documenting everything from crime scenes to parades to celebrities. Dozens of these photos were published by The China Post, a daily paper that once had a circulation of 30,000.

The rest, however, were left in disorganized, nondescript file boxes that were completely overlooked by his nieces and nephews when they cleaned out his apartment in the Confucius Plaza Apartment Complex — Bocian was one of the only non-Chinese residents during the time he lived there.

But in a remarkable turn of events, the photographs were rescued by a longtime friend, Chinese-American actress Mae Wong. The Museum of Chinese in America partnered with the Center for Jewish History to display Bocian’s work in an exhibit titled “An Unlikely Photojournalist.” The exhibit opened in person in August and has recently been extended until March 21.

“I was amazed by the amount of photographs he took in Chinatown and disconcerted by how little recognition he received,” Kevin Chu, assistant director of collections at MOCA, told The New York Jewish Week. “We wanted to tell a story about Bocian and his relationship to the people and places he was documenting.”

Bocian took many shots capturing excitement around the neighborhood, like when Muhammad Ali was honored in New York’s Chinatown on Dec. 9, 1974. (Emile Bocian, Courtesy of Museum of Chinese in America)

The partnership between MOCA and the Center for Jewish History emerged in 2016 as part of a grant project exploring intersections of the Jewish and Chinese immigrant and refugee experiences, which resulted in the digitization of MOCA’s archives at the Jewish institution.

“For generations, Chinese and Jewish immigrants and refugees have lived side-by-side in Manhattan’s Lower East Side and Chinatown neighborhoods,” Rachel Miller, chief of archive and library services at the Center for Jewish History, told The New York Jewish Week. “Not only have these communities felt the familiar weight of American xenophobia, exclusionary practices and assimilation pressures, they have also followed similar labor patterns in the garment industry and have attracted the problematic stereotype of ‘model minorities.’”

“Serious, comparative analysis of American Jewish history and Chinese-American history is hard to come by,” she added. “But cross-community projects such as ours will encourage new investigation and facilitate greater awareness around all that connects us in our overlapping struggles and successes.”

Throughout the digitization process, archivists at both museums were drawn to the photojournalism the bespectacled and bowtied Jewish photographer had accomplished in Chinatown — despite his status as an outsider to Chinese culture, and the fact that he spoke none of its languages.

A 1975 protest against police brutality after Peter Yew, a member of the Chinatown community was killed by the police. (Emile Bocian, Courtesy of the Museum of Chinese in America)

Bocian, whose day job was in public relations, may not have been in the business of “serious, comparative analysis” between the Jewish and Chinese communities (his interest in Chinatown was first piqued when he did press for a Kung Fu film). But through his photos, he immortalized quotidian aspects of life that immigrant communities throughout New York shared: —the communal celebrations, the pride and the fear of being “other,” the small-town feel of ethnic neighborhoods that often provide a contrast to the anonymity of big city life.

Though Bocian was relatively unknown during the time he worked in Chinatown, his photos show an attention to detail and an enthusiasm for the vibrancy of New York’s niche communities. Co-curators Chu and Lauren Gilbert, the senior manager for public services at the Center for Jewish History, were able to recover a few documents about his life that illuminate his character, including correspondence with mentalist and magician Chan Canasta, who was also from a Polish-Jewish family.

In his letters, Bocian explains that he fabricated a tale that he was born in Kaifeng, a city in China that was once home to a small Jewish community — as a joke, but also to win over the trust of local residents. “As a veteran PR man, Bocian never let the facts get in the way of a good story,” the exhibit touts.

In a 1976 letter to Canasta, Bocian humorously compares his observations on Chinese and Jewish New Yorkers. “I’ve become something of an expert in Chinese affairs,” he writes. “I know more Chinese groups than the average Chinese in New York. It’s simple. I think Jewish. There are Fifth Ave, Park Ave, West Side, Uptown, Westchester Jews. The same for Chinese. The Fifth Ave Chinese don’t talk to the ‘downtown’ Chinese. Just like the Uptown Jews don’t talk to the Lower East Side Jews … Anyway this is the first time that ‘downtown’ New York Chinese had a professional Press Agent helping them.”

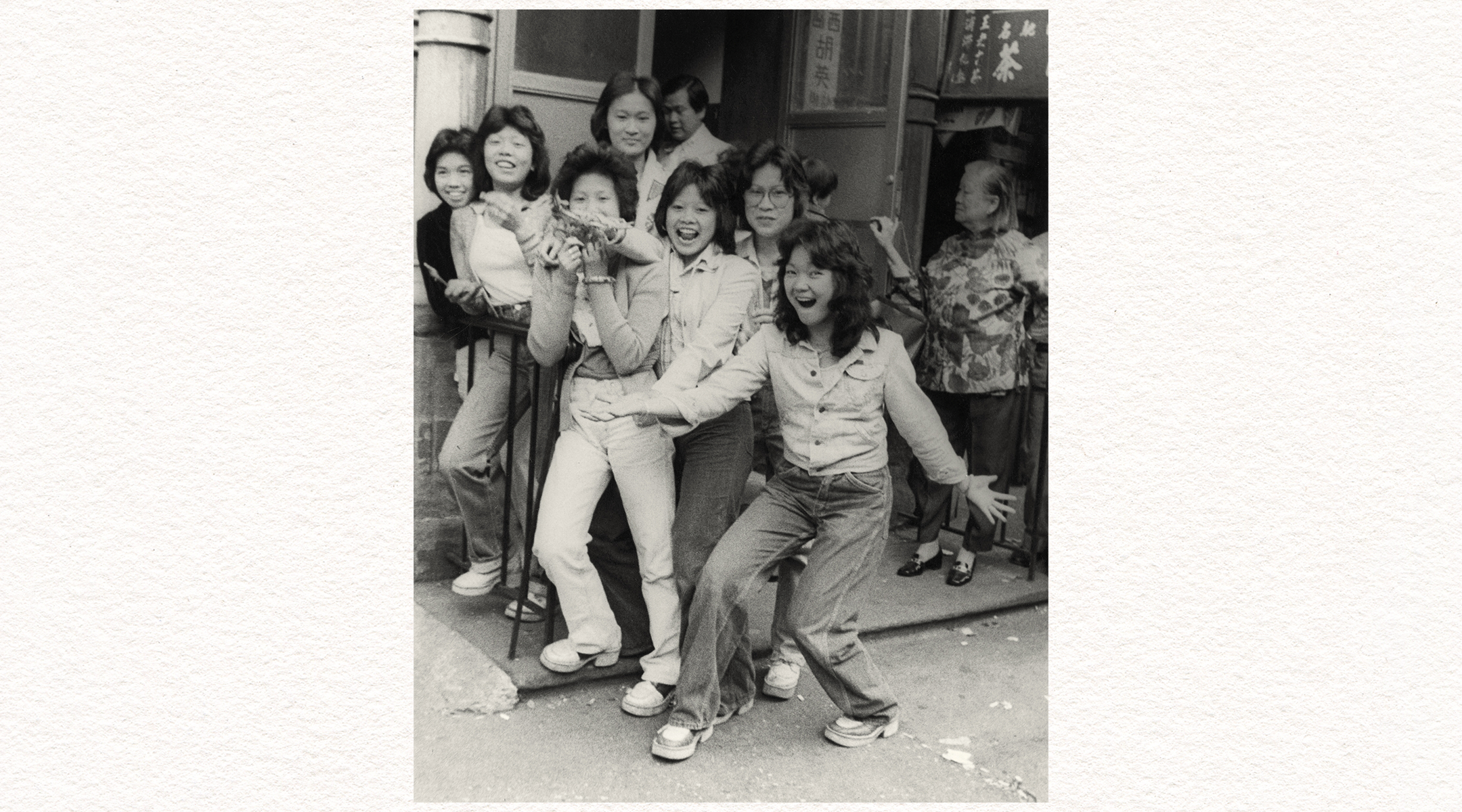

Bocian captured the joys of daily life at all ages in his thousands of photos. Above, a group of teenage girls laugh and pose for the shot. (Emile Bocian, Courtesy of Museum of Chinese in America)

“An Unlikely Photojournalist” also saved Bocian’s work yet again. On Jan. 23, 2020, MOCA’s historic building at 70 Mulberry St. caught on fire. Hundreds of artifacts were damaged — but boxes of Bocian’s photos were safe at the Center for Jewish History, where they had been moved as part of a digitization effort and in anticipation of the exhibit.

(With community support and intense conservation efforts, 95% of the materials from the museum were eventually recovered, Chu said.)

The fire — and then the pandemic — delayed the exhibit’s opening. But Chu and Gilbert produced an extensive, interactive online exhibit and photo gallery in December 2020, which is still online today.

The co-curators said that, since coming online, dozens of people have reached out to them – some who had lived in the neighborhood, some who were relatives of those in the photographs, and some who were in the photographs themselves.

“It was incredible,” Gilbert told The New York Jewish Week. “So many more people were able to access these photos than if they had only appeared in person, and we were able to fill in so many gaps in our knowledge from people reaching out to us.”

In one such example, Bocian had photographed a double date of two young couples. Someone who saw it online contacted Gilbert to let her know that one of the couples eventually got married and lived a long life together.

“It makes me wonder how many other materials and collections are lost forever because no one thought to save them,” said Chu. “I hope that this show has inspired people to document their own communities.”

“An Unlikely Photojournalist” is currently on view at the Center for Jewish History at 15 W. 16th St. The exhibition was recently extended until March 21.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.