PHILADELPHIA (JTA) — As Election Day arrived during perhaps the most charged campaign in recent history, many eyes have been on Pennsylvania, a swing state that both the Biden and Trump camps see as a must-win. While commentators and security experts had warned about the possibility of politically motivated violence on Election Day or in its aftermath, Pennsylvania’s political diversity made it seem like a fertile ground for such tensions.

But at around noon on Election Day in the North Philadelphia neighborhood of West Oak Lane, the biggest problem faced by three local rabbis who had signed up as election volunteers was how close they could stand to the door of a polling place.

The polling place, a senior citizens center, served a largely African-American neighborhood. The building was open to the public, but people had to buzz into a locked door in order to cast their ballots. In the end, the volunteers decided to position a person close to the door to help frustrated voters, just in case.

The rabbis had trained to de-escalate tension that could lead to violence and to advocate for people who were being denied access to the ballot box. As of the early afternoon, the locked door was the most severe issue they had encountered.

And even as votes continued to be counted in the state, Election Day passed calmly, belying fears of unrest in the streets that could disrupt the voting. While cities across the country braced for large protests, including some that boarded up stores in their commercial districts, such demonstrations had yet to happen as of Wednesday morning.

“I feel surprised,” said Rabbi Annie Lewis of Temple Beth Zion – Beth Israel, a Conservative synagogue in central Philadelphia. “Obviously, leading up to this day, I didn’t know how I would feel this morning. I was just very moved, hearing stories on the radio, seeing people voting, being out and talking to voters, talking to poll workers and other volunteers.”

She added, “That feels hopeful to me. I feel part of something much bigger.”

The rabbis were there on behalf of a nonpartisan group called Election Defenders, which aims to assist voters waiting in line and potentially de-escalate conflict at the polls. They were also organized in the effort by T’ruah, a liberal rabbinic human rights organization. Election Defenders has a presence across the country but has focused on mobilizing volunteers in swing states. Its goals range from providing water and masks to voters to stepping in between voters and armed groups that seek to intimidate them.

Voter suppression and the process of vote counting have been core elements of the end of the campaign cycle. President Trump had repeatedly railed against the mail-in voting process in the lead-up to Election Day. He declared victory on prematurely following Election Day, even as results in battleground states were still being tallied. He falsely accused his opponents of trying to “steal” the election by counting votes, and vowed to go to the Supreme Court to stop the vote counting.

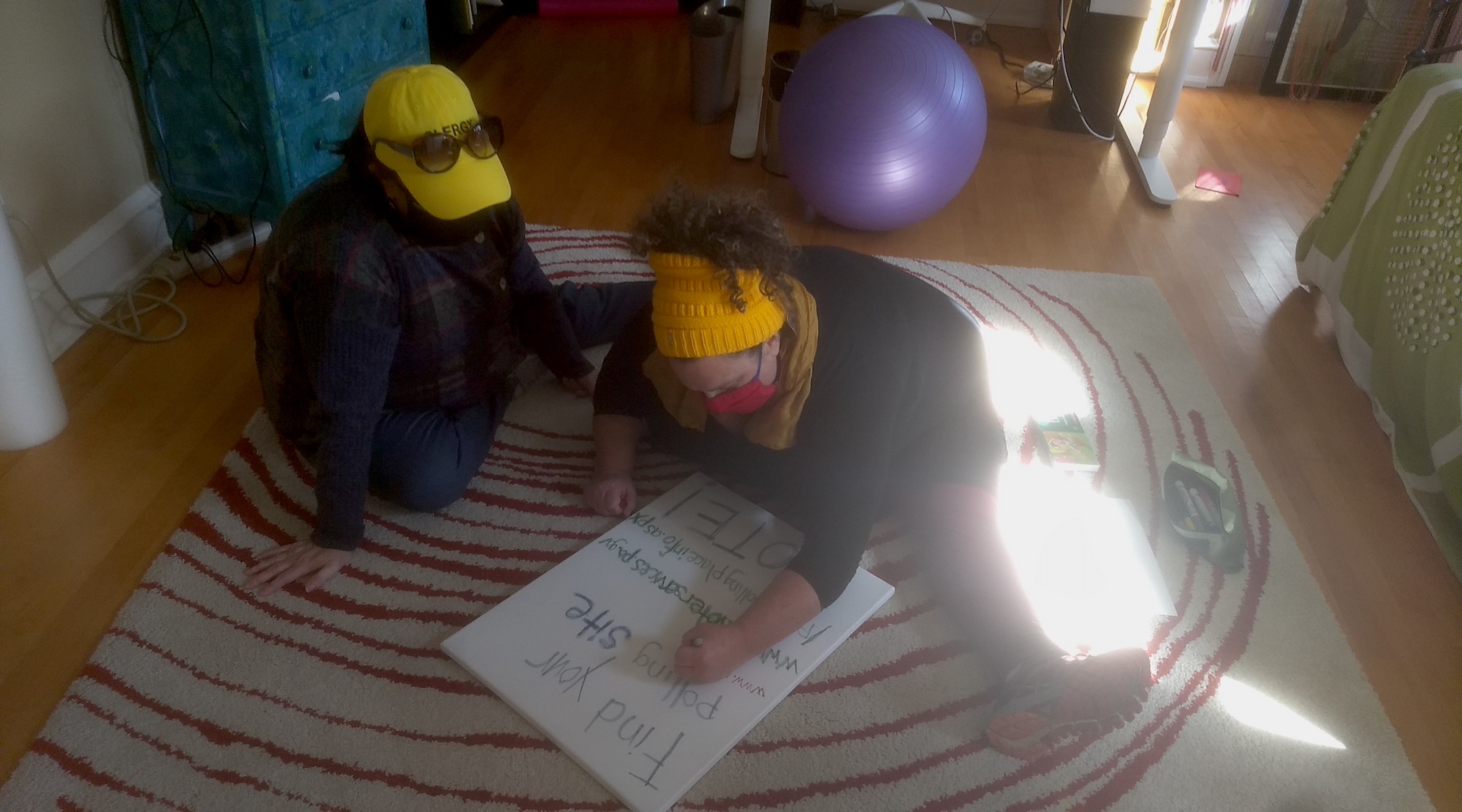

The Election Defenders rabbis, all wearing yellow hats with the word “CLERGY” on them, had been roving between polling places in North Philadelphia to make sure all was calm and that people who wanted to vote could do so. All three said the work was driven by a belief in the importance of democracy.

Rabbi Elyse Wechterman, left, and Andrea Jacobs prepare a sign used to aid voters. (Ben Sales)

“Democracy only functions when every vote is counted and every member of society has a say in how they are governed,” said Rabbi Elyse Wechterman, executive director of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association and a local resident. “I think clergy are in some ways above the partisan strife. Of course I have my own opinions but the reality is I’m not really here to push a candidate … and I think clergy stand for that kind of fairness.”

Even as Election Day proceeded calmly — the rabbis helped one woman find the correct polling place, and put up an informational sign at another polling place that had moved — they were worried for the days ahead, when uncertainty about the election’s outcome and the Trump campaign’s legal challenges could lead to unrest.

“I’m a little bit more concerned about the risk of working in de-escalation, showing up in the streets as clergy, to show up even as a witness at actions in the city in the days to come, in the event that there is’t a clear winner,” said Rabbi Yosef Goldman, Lewis’ husband and the leader of the rabbinic volunteer team. “I’m worried about agitators coming to potentially stop the ballot count or there being lawsuits and things like that that lead to uncertainty about the election and the legitimacy of the election.”

For now, though, that was all a future possibility. After making the rounds of local polling sites, the rabbis took a lunch break in a nearby park, where they were joined by some other Jewish election volunteers. After recapping the morning, the conversation quickly turned to COVID-19 rates in the northeast, and then to the relative merits of kugel, the Ashkenazi Jewish baked dish.

Before they headed out on another round of election monitoring, the Jews posed for a group photo, and debated whether to make peace signs or give a thumbs-up. Do “something badass and nonpartisan,” Goldman said.

When asked what was on his mind today, he said “My children, and wanting America to be a place that upholds the values that we say it does so that it can be a safe and nurturing place for them and for all of the children in our city and country.”

“Sometimes hope is a radical act. We choose and choose again to have hope in what the future can bring,” Goldman said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.