This article originally appeared in Alma.

A woman I quarantined with inadvertently shamed me on a regular basis. As strange March rolled into tragic April which rolled into tragic and strange May, she found ways of keeping herself occupied that were both maddeningly self-enriching and deeply sophisticated.

Though we are related, our approach to quarantine was different. As she watched the French film “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” and the French series “The Bureau,” both sans subtitles, there was no limit to how depraved a show on Bravo might be — it didn’t matter, I’d gleefully watch it. She played bridge on her iPad each afternoon — lessons and tournaments in which she competed for cash; I debased my education by learning about the ins and outs of the TikTok “Hype House.”

Where my social Zooms petered out as the spring festered, she remained invited everywhere: into people’s living rooms for birthdays, bat mitzvahs, even the occasional bris. As ambulances ravaged our home city, New York, and death tolls mounted, we both turned to food. I’d botch Alison Roman recipes by day and by night, smother cream cheese frosting onto cinnamon buns and then lick it off the spoon. She’d slow cook ratatouille and regularly remind me that she drinks at least nine glasses of water by 6 p.m. Infuriatingly, she did online yoga, kept up her skincare routine, and wore swaths of flattering lipstick.

Even seeing no one, her style could be described as uptown-doyenne-takes-a-day-trip-to-Brooklyn-galleries. She wore sweatpants, yes, but they were somehow chic paired with sumptuous cream cashmeres, well-ironed button-down Oxfords, and several different pairs of festive Birkenstocks. It was a good day if I wore a bra, or better, something that I didn’t wear the day before.

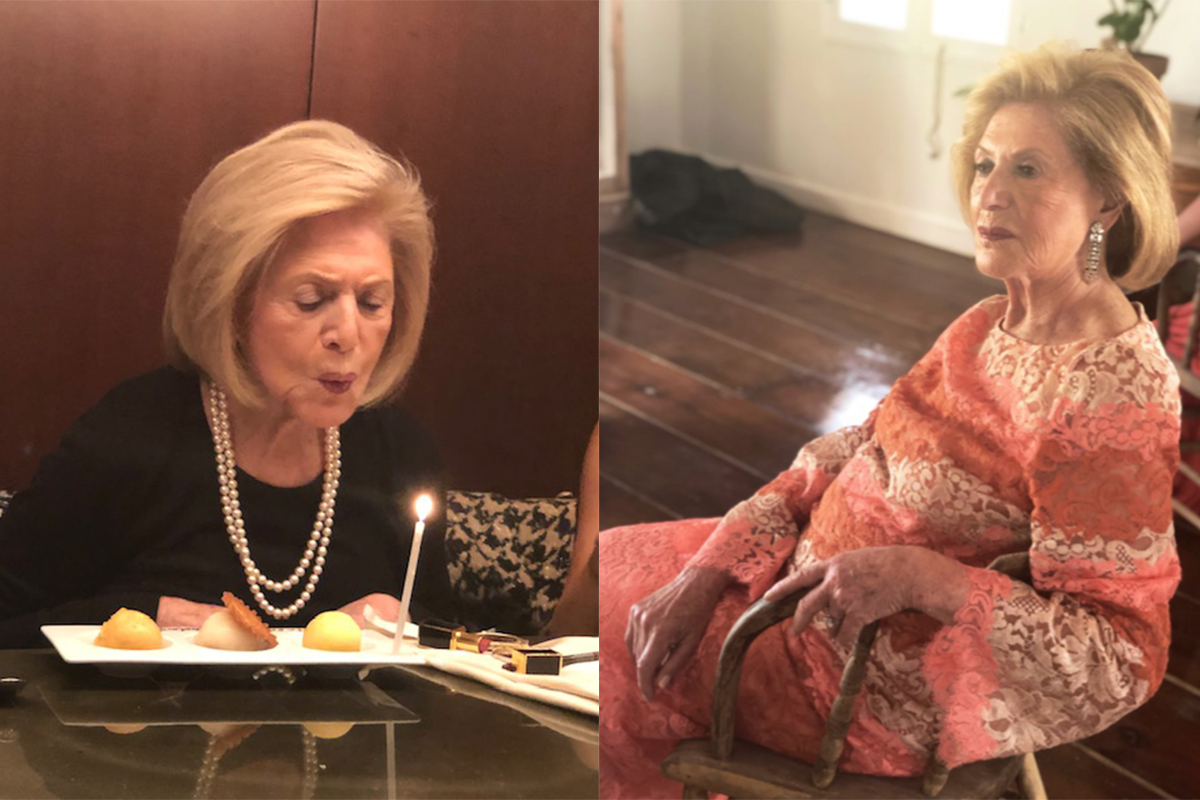

This woman was, of course, my octogenarian grandmother — we call her Oma — who, for a variety of reasons, my husband and I found ourselves quarantining with from mid-March to July.

She didn’t mean to shame me; she was just better prepared to live in a “Cool Zone” of history — as in a “period in history that’s super cool to read about, but much less cool to live through.” Oma is no stranger to “cool zones”: She was born a Jew in Arad, Romania in 1934, where her family narrowly side-skirted the Nazis and then had to flee from the Soviets in 1947 on foot and horse to Belgium. There she met my grandfather, himself a survivor of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen.

Fast forward seven decades, two children, six grandchildren and widowhood; my grandmother is now a bona fide New Yorker. And like any New Yorker with taste and an independent streak, she has her preferences: her favorite butcher and shoe cobbler, her favorite companion for the symphony and art house movie, her favorite walking route around Central Park and mille-feuille.

She made fierce friendships with people of all ages and enjoyed hosting in her apartment, foisting chicken soup, braised veal and her hatred of Donald Trump onto her guests. Like all of us, she would lose this freedom and independence in quarantine; unlike us, she didn’t have the assumption of many decades of her life to regain it, a hard truth we watched her reconcile with.

But she didn’t succumb to gloom. She had the constitution of a survivor, a word that takes on another meaning when paired with the historical circumstances of her life. Interestingly, throughout our childhood, it was my grandfather’s story we focused more on, perhaps because it was gendered or simply because his story — tragic, sprawling, epic — fit better into the well-known Holocaust narratives than my grandmother’s. And indeed, it is common to define a “Holocaust survivor” as someone who endured concentration camps as my grandfather did. Compared to my grandfather, Oma’s story seemed almost privileged: Her parents and sibling lived. (Of course, privilege is extraordinarily relative in this context.)

As we grew older, however, we learned more and more about my grandmother’s story. And even putting aside the insane and difficult details of her displacement, the fact of being a Jew living in Europe at that time by definition makes her a survivor in my opinion — which is to say she survived.

In a different life, I like to imagine Oma would have made an excellent diplomat or foreign dignitary. She is a language savant, with a breadth developed by a preternatural giftedness but also by necessity of the different countries she has lived in. Oma speaks eight languages: English, French, German, Italian, Romanian, Hungarian, Hebrew and Yiddish. One quarantine dinner, when all we wanted to talk about was “the numbers,” Cuomo, and PPE on repeat, trying to understand what the hell was going on, Oma wanted to discuss language — and particularly, how pitiful it was that us (Americans) could barely speak two. This needling, in the time of COVID-19, was refreshing.

Another time, she gently suggested my husband shave his beard and less gently suggested that I might brush my hair once in a while. She did not understand my droopy bright sweatpants or the tie-dye trend, as if she could alone predict the fallacy in the idea that sorbet colors all bleeding together onto a T-shirt could negate the thousands, then tens of thousands, and now hundreds of thousands of people who have died.

We shared one crucial thing in common: We couldn’t believe we were living through this. A little over two months into it, shortly after George Floyd was murdered and protests erupted across the country, she looked at me and said, “This may be the craziest thing I’ve ever lived through.” After what she’d been through, it was surprising to hear, yet another example of how relative privilege is. But it was also strangely validating to hear someone with so much perspective, who has lived so much life, express that none of this was close to normal.

Though not normally highly sentimental, another thing she said was, “I’m so happy I got to know you.” Though we had been close my whole life, we gained a new understanding that comes with living with one another, observing each other’s patterns and rhythms up close without a place to go or anything to do, under the specter of a global health crisis. I got to know her, too, and I know in many ways, her life-must-go-on, Jewish survivor ethos carried me through.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.