This article originally appeared on Alma.

(JTA) — I’m in 4th grade and we are doing a project in geography class. We have a week to hand in a folder of research and pictures on any chosen country. I go to the local travel agent with my mom and pick up a copy of the “Exotic India” brochure. I cut out pictures of tigers and women in saris and stick them in the blank pages of my folder. Proud of my work, I hand in my folder, excited to see what comments my teacher will give me, already anticipating showing it off to my classmates.

The following week, my teacher hands back the project and I see her comments:

Good work Lishai, but there are many spelling mistakes and you did not explain why you chose this country or what interests you about India.

If this were a university project, I would have received a C, maybe a C+, which is pretty much equivalent to how I felt as an Indian: at best, only passing.

Growing up in Yorkshire, England in an Ashkenazi community, our family was different than most. In the small suburb that we lived in, on the lip of a northern city, always surrounded by reminders of English sensibilities, we stood out with our brown-skinned mother, her lateness, her thick accent, how she always talked too loudly. She was Israeli in her mannerisms, her gestures and her propensity for arguing. But her face belonged to India, to the long line of women whose features are chiseled from centuries of living in the Konkan coast.

My mother had an uneasy relationship with living in a white Jewish community. She never fit in. She tried to adapt, but she straddled an intersection of being both Israeli and Indian that was simply incompatible with her new adopted home.

Perhaps this is why I grew up so divorced from my Indian roots. To ensure her children never doubted their right to a seat at the (very British, very Ashkenazi) table, she tried to downplay her differences, inadvertently making them all the more visible. She was born in Mumbai in the 1950s and moved to Israel at a young age before memories of her early life in India could really take root. She grew up in Israel, met my English father while he was on vacation there, and married and had my brother and me before my father decided to relocate us all back to his home city.

This was not the first time assimilation was required for my mother to gain access to group membership. Soon after the Israeli state was created in 1948, there was a mass exodus of Indian Jews, known as Bene Israel, who arrived in the “promised land” only to be faced with racism and rejection by their fellow Jews of European origins. Like other non-Ashkenazi Jews, they were allotted inferior housing and faced income disparity and employment discrimination. In 1962, the Rabbinic Council announced that Bene Israel community members would have their maternal ancestry investigated if they wanted to marry Jews from other communities. This constituted a sort of crisis within the community, and although this ruling was eventually overturned, it left deep scars.

This context of discrimination served as a backdrop for how the children of Bene Israel immigrants would find their place in Israel: assimilate completely or be ostracized. The less visibly Indian, the more accepted in Israeli society. My mother never learned to speak Marathi or Hindi, never returned to her homeland, never learned the Bene Israel customs and traditions. She spoke Hebrew, served in the IDF, and belonged more to Israel than to the country she was born to.

In my childhood home in England, there were a few reminders that we were connected to India. A sandalwood coffee table, a teak vase, a statue made of elephant tusk, some saris collecting dust in the closet. Beyond these relics, my mother had nothing to offer me in terms of my Indian heritage because it had all but been scrubbed out of her before she could claim it.

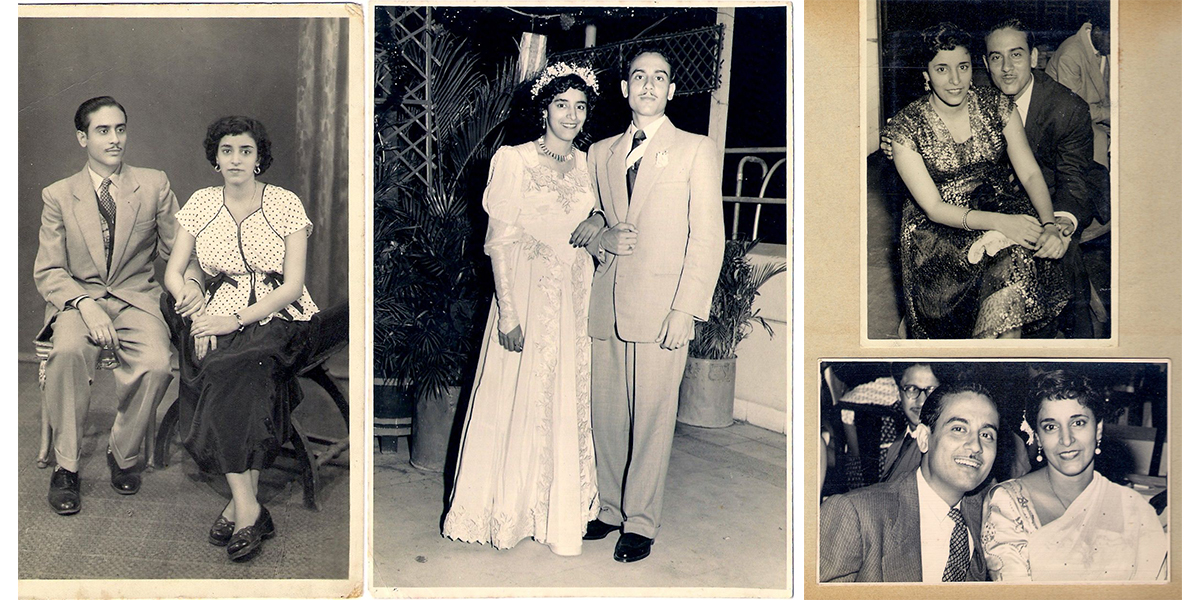

Lishai’s grandmother and mother (Courtesy)

But when my grandmother would visit once a year, she would fill my head with stories of India that captivated me and filled me with wonder. They inspired in me something that demanded attention, something that needed to be excavated and understood and helped me locate myself as both Jewish and Desi. My grandmother’s stories served as a portal by which I could begin to know this heritage I was so completely removed from.

There was the haunted house in Trivandrum where my grandmother spent her early years. The circus her father owned in South India where she has vague memories of crying hysterically on a Ferris wheel. There was the British soldier who fell in love with her and stood outside of her parents’ house in the rain every day during monsoon season until he disappeared soon after the British packed up and left. There was the violence of 1947, the sound of molotov cocktails being thrown between the Hindu and the Muslim neighborhoods in south Mumbai — the only buffer between them, the then Jewish quarters of Bayculla. There was the older sister who died of tuberculosis and whom everyone believed my grandmother was the reincarnation of (many Bene Israel adopted a belief in reincarnation from centuries of living with their Hindu neighbors). There was the bear my great uncle kept in a cage and who escaped one day, causing havoc and terrorizing the streets of Bayculla. There was my great uncle who enlisted in the British army, only to covertly work for the Jewish Resistance Movement and eventually disappear before the conclusion of World War II. My great-grandmother lit a candle for him every day of her life in the hopes that he would come home.

Through my grandmother, I came to associate India as a place full of ghosts, lost children, deep faith, and unfinished stories.

Lishai’s Safta and Saba (Courtesy)

When I arrived in India for the first time, I was on the cusp of motherhood, not yet knowing that I was pregnant. I traveled with a crushing exhaustion as my body grew a new life inside me. Surely, I should feel more Indian, more connected to this land, I thought. But as it turns out, I felt only like an outsider in a country so vast and so unknown to me.

It took me five years to return, this time with my child and his dad. We lived in South India for six months by the Arabian Sea and made some important connections, new friendships and incredible memories. But still I felt like an outsider.

It was only in Mumbai, when I was standing in front of the synagogue my grandparents had been married in, that I felt what I had always dreamed of feeling — a sense of belonging. The sun’s halo danced behind the building’s clock tower and I looked up in awe at the pale blue arches, towering over me the way they had the day of my grandparents’ wedding. I could suddenly see that this little piece of architecture has a history, and that history is my history, too.

The author Mumbai (Courtesy)

Perhaps it is enough to know through stories that we are part of a narrative that is bigger than us. I may never truly know this country and she may never know me. What I hope is that I will inspire my son with stories the way my grandmother inspired me, so that he will one day understand that the history of the Bene Israel is written not just in his DNA but in the stories we tell that keeps the flame alight.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.