(JTA) — The first thing Jerry Stiller said to me when we met was a compliment.

Several weeks earlier, I had interviewed him over the phone for an article tied to an appearance in an HBO miniseries. But Stiller’s roots were always in the theater, so despite his successes, it wasn’t surprising to find him in the smallish regional Westport Country Playhouse in Connecticut, where I had arranged to meet him.

He was starring in “After-Play,” a brilliant examination of life at midstage as seen through the eyes of two couples who go out for a post-theater drink. A discussion about the play they’ve just seen leads to talk about the various scars that life inflicts, such as parents who are hurtful to children who have gone astray.

It was a grueling performance. He was on stage for nearly the entire 90 minutes, without intermission, and ran the gamut of emotions from joy to anger to unbearable sadness. I was leery now: Given how draining his performance was, I felt that the conversation I’d anticipated would not actually happen.

As it turns out, Stiller loved the playwright — literally. She was also his co-star on stage and in real life: Anne Meara. Perhaps that was the reason there was a particular bounce to his step as he greeted well-wishers in a hospitality tent set up behind the theater. A jazz guitarist (who gave him two CDs), a show business agent and some people who knew him years ago popped in to say hello.

When I introduced myself, he excused himself from those folks.

“I was trying to figure out which one you were,” Stiller said.

He couldn’t understand how I’d managed the article based on our brief phone conversation, and he made it seem as though it was the best thing ever written about him.

Typically, celebrities can be your best friend when you help them promote their latest ventures, but after that they understandably disappear.

But Jerry Stiller wasn’t typical. For several years after that late 1990s interview and the play, I’d receive High Holiday cards from him and Anne, who I met briefly that evening. I had his phone number and email address, and he always made himself available if I needed a quote. In fact, once an editor at a paper, knowing my relationship with Stiller, wanted me to ask him a favor. Someone died, and the editor wanted to know if Stiller would write a tribute. He did.

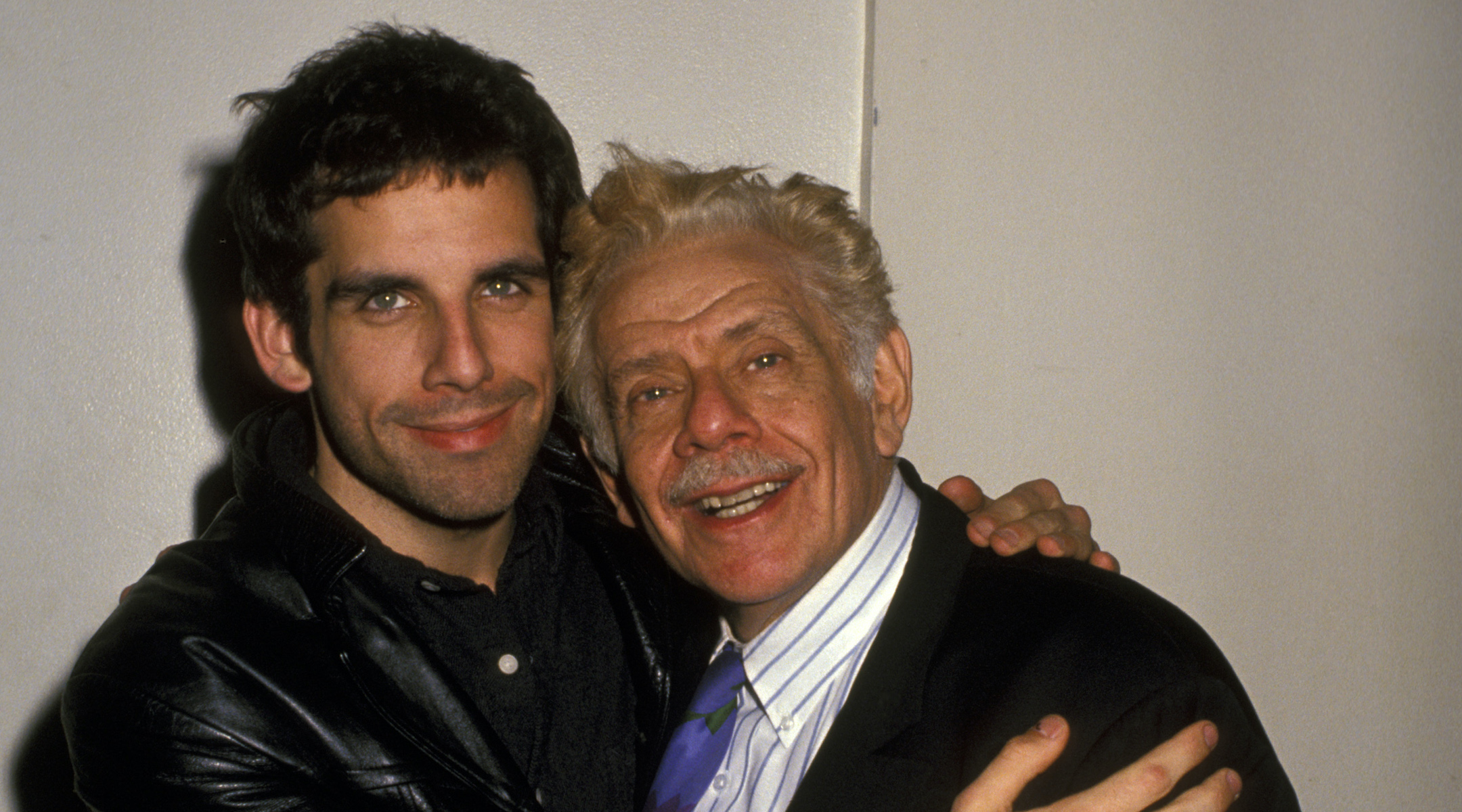

In fact, over the many times I asked something of him, the only time he declined was when I wanted his help arranging an interview with his son, Ben. He wouldn’t get involved in that.

The last time I saw Stiller was about five years ago. Ben was appearing in a Broadway show and dad was there every night to watch and cheer him on. I went over at intermission and reintroduced myself. It took him a few seconds, but he remembered and greeted me enthusiastically. We spoke until the start of the second act.

News of his death prompted me to return to the stories I’d written about him, and while much of his professional (the Stiller and Meara act, “Seinfeld” and “The King of Queens”) and personal life have been covered, I realized that he told me some things over the years that I haven’t seen elsewhere.

Jerry Stiller with his son Ben at a party for the play “What’s Wrong With This Picture” in New York City in 1994. (Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

It started on Jerome Street in the largely poor East New York section of Brooklyn — the first of a series of brief stops on the road to adulthood.

“I remember very distinctly that we moved 11 times in the first 13 years of my life,” Stiller recalled. The moves invariably were tied to staying one step ahead of a pursuing landlord.

“If there was a dark side to my life, it was moving around all those times. It meant you were losing friends every time you move,” he added. “And when we were kids, we always had to do something to get the kids in the new neighborhood to include you in punchball games and stickball games.”

His father was a cab driver, not the best of professions during the Depression. Finally his father landed a job as a bus driver — after his wife and sister-in-law cashed in a small Irish Sweepstakes winning ticket, enough to pay $500 to someone at the bus company for a job.

Stiller caught the acting bug at the Henry Street Settlement, which at the time largely served Jewish immigrants living on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

“It ignited a spark in me that made me want to become an actor,” he said.

His first role came in a high school play, where he played Hitler. It was a comedy in which the German dictator went to heaven and was reformed.

“It made me aware for the first time that I love making people laugh. And from that point on I knew that I wanted to become an actor,” he said. “The theater lifted me up.”

After school and a stint in the military, Stiller did what all young actors did: made the rounds. At one agent’s office he was introduced to the young woman with an appointment before his, an Irish-American girl named Anne. She came out of the office screaming that the agent had chased her around the room. Gentleman that he was, Stiller invited her for a cup of coffee.

She immediately impressed him by sticking some of the silverware in her purse for later use at home.

“I thought she was kind of interesting, someone with guts like that,” Stiller told me.

He would marry Anne Meara, who would later convert to Judaism. Stiller told me that she was chiefly responsible for the family’s observances of the faith, like getting Ben and his sister Amy off to Hebrew school and making holiday meals.

Years later, Stiller actually had to turn down the role of Frank Costanza on “Seinfeld” when he was first contacted about it. He had just gone into rehearsal for a play in New York (“Three Men on a Horse” with Tony Randall and Jack Klugman). Another actor was cast and appeared in one episode, but when that didn’t work out, the “Seinfeld” people contacted him again. This time he accepted, fortunately for all of us viewers.

Stiller remembered the end of his first show, when the cameras stopped rolling and the cast was called out to the audience’s applause.

“That night, when they introduced the actors after the show and he came to me, the audience clapped a little louder. My eyes met Jerry Seinfeld’s,” Stiller said, “and we knew that something was in the air.”

Something special.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.