(JTA) — David Simon originally read Philip Roth’s novel “The Plot Against America” around the time it was released in 2004. An alternate history, it posits that Charles Lindbergh defeated Franklin Roosevelt in the 1940 presidential election, signed a non-aggression pact with Hitler that doomed Britain and promoted an increasingly violent anti-Semitic agenda that ultimately included resettling Jews in remote, rural areas.

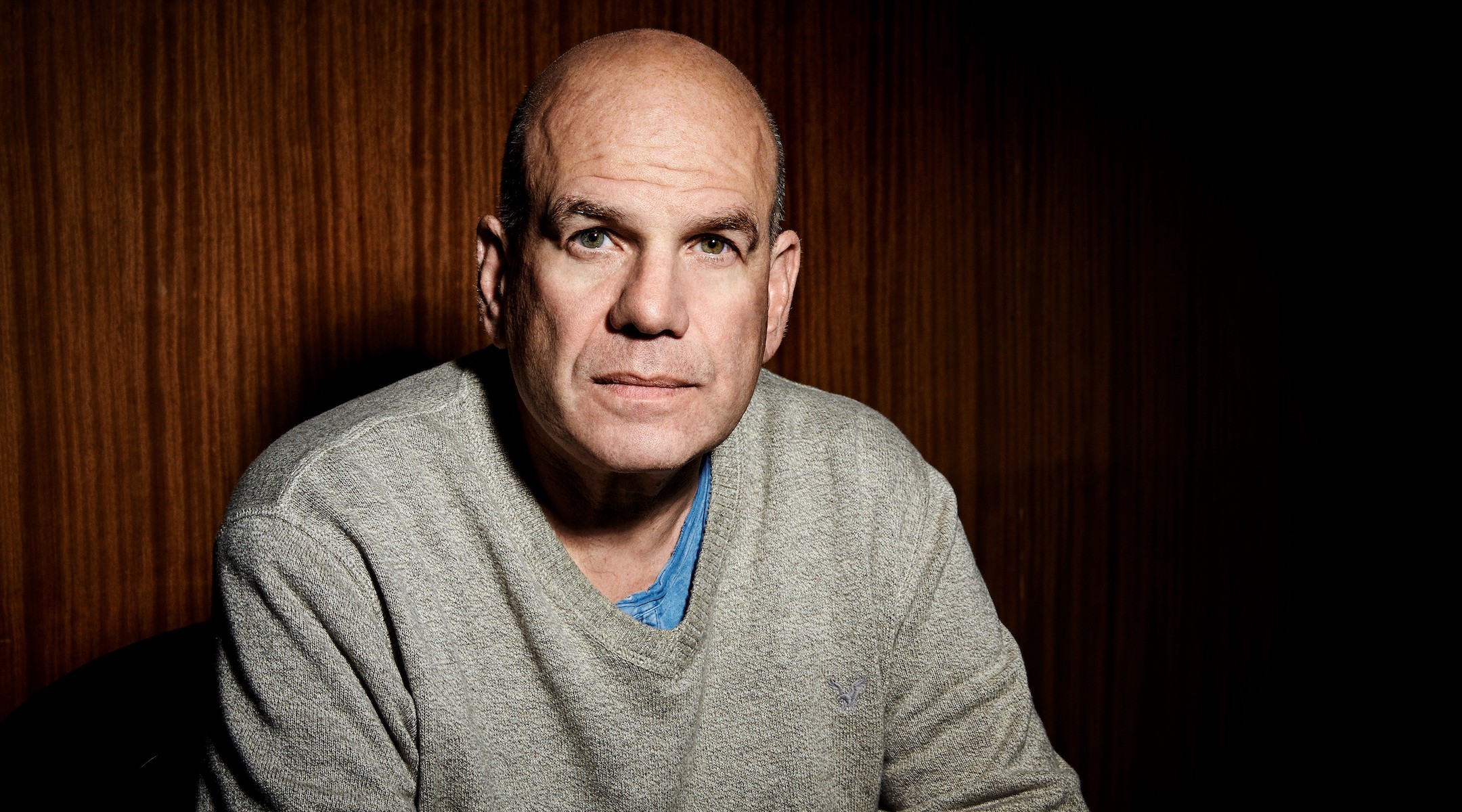

However, Simon, the acclaimed Jewish writer, producer and showrunner of several provocative and groundbreaking series — from “The Wire” to “Treme” to “The Deuce” — was not a big fan of the book.

“I thought it was an interesting artifact in the Rothian cannon,” Simon said in a telephone interview. “It was different from a lot of his works. I was glad that I read it, but I thought America was beyond that moment.”

That changed for him with the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Since then, he believes portions of American society have felt empowered to turn on black and brown people. But in addition to attacks on those groups, he cited violence against Jews, including the shooting at a synagogue in Pittsburgh.

“These are the people being othered. When the hate train gets to leave the station, whenever intolerance is directed at anybody, anti-Semitism follows,” he said. “But I didn’t make this piece as a narrative directed at anti-Semitic tropes. I made it about hate against all targets.”

The result of Simon’s mental 180 is a six-episode HBO mini-series based on the novel that debuts Monday night. The show is claustrophobic in the overwhelming sense of foreboding it builds.

The process that ended with Simon’s involvement actually started in 2013, right after Barack Obama was re-elected. Simon got a call from Tom Rothman (now the chairman of Sony’s motion pictures group) about working with him on an adaptation of the book. Simon told him he wasn’t sure the country was going in that direction, especially after electing an African-American president for the second time.

Three years later, after Trump’s election, Simon had another meeting with HBO executives in New York.

David Simon has adapted the Philip Roth novel for HBO. (Michele K. Short/HBO)

“I told them they should get ahold of this book, a great dystopian novel about American politics. They told me Joe Roth [another studio head] was just pushing the same thing,” Simon said. “But they thought they were a little late to the party. With ‘Man in the High Castle’ and ‘Handmaid’s Tale,’ they thought they missed the window.”

When Simon returned to his office, he asked his assistant to call Roth — forgetting that it was Rothman whom he spoke to years earlier.

“I told [Joe Roth], ‘Three years ago, you were right. You were prescient. And I didn’t see it.’ He told me, ‘I’ve never spoken to you,’” Simon recalled.

They figured it out pretty quickly.

“There were too many Hebrews,” Simon says, chuckling. “I told Joe, ‘Oops. I think I just made an ass out of myself.’ But he still asked me, ‘Do you want to write it?’”

The answer was yes, and Simon and his producing/writing partner Ed Burns came up with a cinematic version of the book that remains true to Philip Roth’s uncanny clairvoyance.

The story centers on the extended Levin family.

“I kind of identified with all of them,” Simon said. “They’re all over the spectrum and that is the power of the book. Each of the characters reacted in different ways to the rise of Lindbergh.”

At one end of the spectrum is Alvin Levin, who enlists in the Canadian army and goes off to do battle in Europe. On the other hand is Rabbi Lionel Bengelsdorf (played by John Turturro), who supports Lindbergh, and not only becomes compliant but also a functionary.

In between, there’s the family patriarch Herman (Morgan Spector), who is defiant and stays put while many of his friends and neighbors flee for Canada; his wife Bess (Zoe Kazan), who grew up in an anti-Semitic neighborhood and wants something better for her children; Philip (Azhy Robertson, a doppelgänger for the book’s author) and Sandy (Caleb Malis); and Bess’s sister Evelyn (Winona Ryder), who marries the rabbi.

John Turturro as a rabbi and supporter of Charles Lindbergh in “The Plot Against America.” (Michele K. Short/HBO)

“The book asks the question, ‘Do you embrace the situation or fight? Do you speak up or stay silent?’” Simon says. “It’s an elemental question, and I think we’ve all imagined ourselves at critical, pivotal points in history — what would we do and at what cost?”

Simon brought his Jewish background to the series: Old Simon family photos hung on the walls of the Levin residence. He, and not an acting or voice coach, instructed the actors on proper Ashkenazi pronunciation for scenes in a synagogue.

“I can’t say I didn’t have a little fun accessing my own family history. I didn’t do [the series] for that reason, but having arrived there, I could write a Jewish-American family with ease,” he said.

Simon went to Hebrew School growing up in Silver Spring, Maryland, where he had a bar mitzvah and was more culturally Jewish than religiously so. The family was briefly kosher, but that changed when an older brother who had digestive issues was given some bacon and loved it.

“By the way, he’s not wrong,” Simon says. “I don’t agree with that part of Leviticus.”

Simon believes his Jewish background informed his work in several ways—from his family’s culture of argument and debate to its obsession with books. His father was a journalist who worked briefly for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency and then spent 20 years as public relations director for B’nai B’rith, a global Jewish service organization.

He never experienced any serious anti-Semitism as a kid.

“I felt so assimilated and so fundamentally American, I can’t say I ever felt intimidated,” he said.

Contemporary events like the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting have had a lasting effect on him, though. Ironically, it’s this push back that is in part responsible for his faith, such that it is.

“One of the things that makes me Jewish is the world’s resistance,” he said.

But he also likes the idea of Jewish continuity. Or as he wrote for Alvin Levin, who when asked why he is Jewish replies: “I believe in my father, who was Jewish, and his father who was Jewish.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.