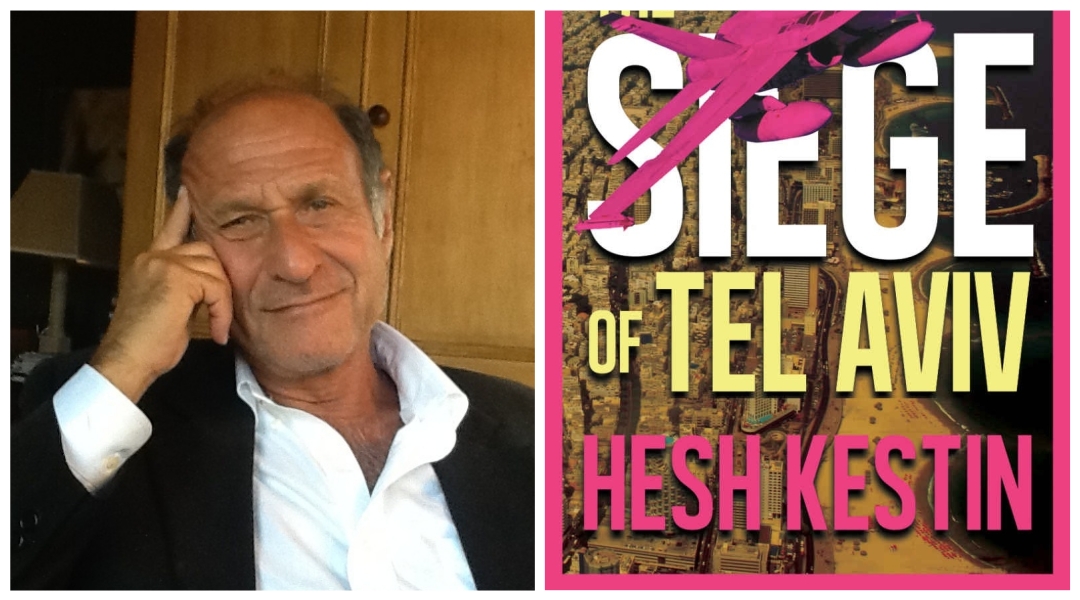

NEW YORK (JTA) — On April 16, Dzanc Books announced its latest release, “The Siege of Tel Aviv,” a novel that imagines an Iran-led attack on Israel that leaves the country decimated.

Author Hesh Kestin, a former journalist who had already published two novels with the small independent press, said the book was inspired by his experience living in Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Stephen King contributed a glowing blurb.

But a week later the Michigan-based nonprofit publisher announced it was axing the book amid a flurry of comments on social media, including from other authors published by Dzanc, alleging that the book is Islamophobic.

The book “perpetuates harmful narratives regarding Muslims that we cannot support, as a house,” Dzanc’s publisher and editor in chief, Michelle Dotter, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in an email.

Meanwhile, the 75-year-old Kestin, who lives in Southampton, New York, but spent two decades in Israel and served in its army, denies the allegations and says nixing the book is an act of censorship.

Kestin has received a $2,500 advance from Dzanc, which he will keep, and the publishing house said it is currently in talks with him to sell him remaining copies of the book. But Kestin told JTA in an email that he neither wants to pay for the books nor remove Dzanc’s name from them, which he says was another demand.

The incident is part of a larger discussion in publishing and beyond about cultural sensitivity.

As publishers hire “sensitivity readers” to ensure books do not contain inaccurate or stereotypical portrayals of minority groups, some say the focus on political correctness is stifling artists. They speak of a “cancel culture” in which publishers are quick to terminate books at the first whiff of controversy.

The controversy surrounding “The Siege of Tel Aviv” started on April 16, when Dzanc tweeted about the book’s publication.

https://twitter.com/dzancbooks/status/1118227176422137856

“Iran leads five Arab armies in a brutal victory over Israel, which ceases to exist … While the US and the West sit by, the Moslem armies take a page from the Nazi playbook — prepare to kill off the entire population,” Dzanc’s description about the book read.

That quickly led social media users — including editors and writers, some affiliated with Dzanc — to say the book’s very premise was Islamophobic.

“This is obviously racist,” wrote Nathan Goldman, an associate editor at the leftist magazine Jewish Currents, in response to the Dzanc tweet.

Poet Cortney Lamar Charleston echoed Goldman’s comments.

“Sending love to all my Muslim homies who have to face such an obvious affront to their personhoods yet again,” he tweeted.

Some critics took offense at the spelling “Moslem” — it’s outdated but still popular among some right-wing critics of Islam — while others noted the description misidentified Iran as an Arab country.

The book imagines a conflict similar to the Yom Kippur War, except this time it is Iran that takes charge when its leaders call for Israel’s destruction, followed by Syria, Egypt, Jordan, Iraq and Lebanon, as well as Hamas and Hezbollah fighters.

Whereas in 1973, when the U.S. came to Israel’s aid, in Kestin’s book the American president — and the rest of the world — watches idly as most of Israel is decimated and 6 million Jews are crammed into a ghetto in Tel Aviv with rapidly dwindling food and water supplies. The end looks to be nigh until an unlikely group of people — Israelis and Americans, Jewish and not — fights back.

Kestin says the reason people were angry with the book has nothing to do with how he portrays Muslims.

“The fact is that I exposed the pan-Islamic dream of making Israel go away as a massacre and a genocide, and that’s what they don’t like because somehow they’re selling this idea that it’s all going to be settled peacefully,” he said in a phone interview last week.

In 2016, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, wrote on Twitter: “As I’ve said before, if Muslims & Palestinians unite & all fight, the Zionist regime will not be in existence in 25 years.” Earlier this year, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif said Iran had no intentions of destroying Israel, but the Jewish state would end up destroying itself.

Kestin also invokes his personal ties to Arabs in defending himself against Islamophobia.

“I served side by side with Muslim and Druze soldiers in Tzahal for a period of 18 years, and I also served under Arab commanders twice,” he said, using the Hebrew acronym for the Israeli army.

“And that’s one of the great secrets of the IDF that sprinkled through it are Arabs — Muslims and Christians. And not only that my family in Houston has a Muslim branch.”

In his book, Kestin is clearly not too concerned with being politically correct. There are few sympathetic Muslim characters other than a Bedouin who comes to the rescue of a stranded Israeli soldier and a Jordanian army general of Scottish origin who tries to convince his country’s king not to immediately kill off the Jews in Tel Aviv.

Several of the other characters also come across as stereotypical. An Israeli pilot’s love of cross-dressing seems thrown in for shock value, the description of Israel’s female prime minister is unnecessarily focused on her reproductive system and breast size, and a black U.S. Air Force pilot speaks in an accent that at best reads as a clumsy attempt at African-American vernacular.

However, these descriptions seem not to have bothered Dzanc enough to edit them out of the version it had been prepared to publish.

Meanwhile, Kestin isn’t too upset about the drama, saying that other than distracting him from writing his next book, the outcome has been positive. He has uploaded the first half of the book to his website and says he has sold thousands of digital copies after self-publishing the book on Amazon and is in the process of finding a way to print it.

“I couldn’t buy this publicity,” he said. “I am very happy with the way it worked out.”

Dotter said that Dzanc had been discussing various options with Kestin — including “a possible revision or re-release or delay” but wasn’t able “to reach an agreement.” That was, she said, “in part because it became clear that Hesh intended to run a campaign based on the controversy.”

“We don’t believe in censorship,” the publisher said. “We chose to revert the rights to give the author the opportunity to keep the book in the marketplace without endorsing it or profiting from the sale of a book, which perpetuates harmful narratives regarding Muslims that we cannot support as a house.”

The author sees the dialogue around his book as having raised a larger conversation.

“Almost any book that can be written, people will find fault and that’s normal,” Kestin said. “But this book has raised a consciousness of people on the right side of history, which are the people who are for freedom of expression, who are for the values of fiction, and who are against censorship and even worse, self-censorship.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.