(JTA) — On a warm summer day in Oslo last year, Kaveh Kholardi heartily greeted spectators at a city-organized concert celebrating diversity.

Kholardi, a popular Norwegian rapper of Iranian descent, wished his fellow Muslims “Eid Mubarak,” a greeting in Arabic for the Eid al-Fitr holiday that marked the end of Ramadan.

He asked whether there were any Christians present, smiling upon hearing cheers. Then he asked if there were any Jews.

“F***ing Jews,” he said after a short silence, adding “Just kidding.”

In Norway, the incident generated an uproar at the time and again last month, when the Scandinavian country’s attorney general cleared the 24-year-old musician of hate speech charges, opining that his slur may have been directed at Israel.

It was a tenuous interpretation considering how Kholardi never mentioned the Jewish state on stage and five days earlier had tweeted “F***ing Jews are so corrupt.”

From a broader European perspective, the incident demonstrates how the continent’s rap scene has become a haven and major avenue for the kinds of hate speech that governments are increasingly determined to curb online and on the street.

That’s a problem because “rap is a catastrophic vector, propagating anti-Semitism to the population most susceptible to it,” Philipp Schmidt, the vice president of France’s International League against Racism and Anti-Semitism, or LICRA, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

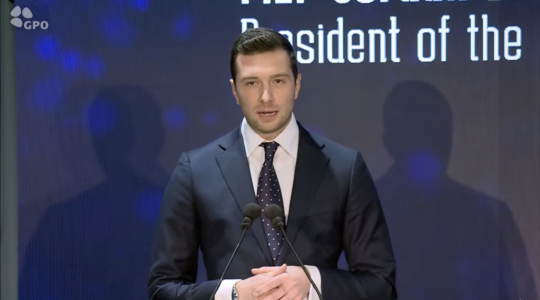

The Norwegian rapper Kaveh Kholardi has cursed Jews and called them corrupt. (Facebook)

In France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and elsewhere, rappers have dabbled in Holocaust denial, anti-Jewish conspiracy theories, grotesque Holocaust analogies and threats against “Zionists.”

As a subculture with distinctly anti-establishment characteristics, the European rap scene has helped lift taboos on anti-Semitic rhetoric while escaping scrutiny applied to hate speech in mainstream forums, said Joel Rubinfeld, president of the Belgian League Against Anti-Semitism, or LBCA.

Denigrating rhetoric, including about Jews, is common in the rap scene worldwide, including in its native United States, Rubinfeld said.

But whereas rap anti-Semitism in the United States tends to revolve around classic stereotypes about Jewish money and power, in Europe it has been augmented by “the utilization of the Arab-Israeli conflict to inflame internal conflict,” Rubinfeld said.

This corresponds to how “rap’s base in the United States is black, and in Europe it’s Muslims from poor suburbs, where anti-Semitism is rife,” he said.

Ben Salomo, a German-Jewish rapper, noted the trend in an interview with the Arte television channel in 2017. The Palestinian issue is gaining traction in Germany’s rap scene, he said, along with anti-Semitic conspiracy theories.

Approaching the Israeli-Arab conflict “legitimizes in their mind hate speech against Jews,” Salomo said of some of his fellow rappers.

But the problem goes deeper than the rap scene itself.

“Rap reflects society. If this rhetoric didn’t correspond to what people really think, rappers wouldn’t say it because they are above all demagogues and populists writing about popular themes to sell albums,” Salomo said.

Unlike in the United States, Rubinfeld said, rap in Europe is becoming an intersection point for the far right, far left and Muslim anti-Semites.

Take Alain Soral, a well-known French Holocaust denier from the far right. In 2014 he briefly recruited into his Equality and Reconciliation movement Jo Dalton, a black rapper and self-described promoter of “black rights.” The partnership did not last, though, with Dalton leaving, complaining that Soral was “siding with fascists.”

Soral, an anti-gay nationalist, in interviews has called rap “crap imported from America” that he can’t enjoy because he is “too cultivated.” But when it comes to spreading anti-Jewish sentiments, he acknowledged in a 2012 interview, “it gets the job done. It’s effective.”

Another case in point was the January release on YouTube of the “Yellow Vests Rap,” a single celebrating the protest movement launched last year in France. The song is rife with anti-Semitic references, and its official video features the burning of portraits of three French-Jewish celebrities and the logo of the Rothschild Bank.

The video was viewed many thousands of times before it was finally removed, but was quickly reposted on YouTube and elsewhere.

“When we speak of media, we need to talk about Patrick Drahi running the show from Israel,” the lyrics go against images of a man wearing a shirt reading “Palestine” burning a sign reading “Rothschild.” Drahi is the French-Israeli businessman who founded the cable and telecom company Altice Group.

The French “won’t stand for those parasites anymore,” the rap also says over pictures of banners denouncing the “Rothschild Family’s grip on power.”

That clip and many others demonstrate how “in the rap scene, Jews are used as the hated face of all whites, of France itself,” said Michel Serfaty, a Morocco-born French rabbi who heads the Association for Friendship between Muslims and Jews.

Authorities have taken note of the incitement in rap. In March, a French court fined the rapper Nick Conrad some $5,500 for a 2018 single that begins with the words “I go to kindergartens to kill white babies/I catch them quick and hang their parents/I tear them apart to pass the time/to entertain black children.”

The explosion of anti-Semitism in the European rap scene preceded by several years the current protests over austerity.

In Belgium, up-and-comer Bissy Owa inveighed against “Zionists” during a performance last year on a state-funded radio station. He also performed his hit single “Money till the Death.” Its official video shows Owa, who is Muslim, dancing while wearing a black hat and fake sidelocks and singing about Jewish greed.

“I can’t hang with a Jew,” he rapped.

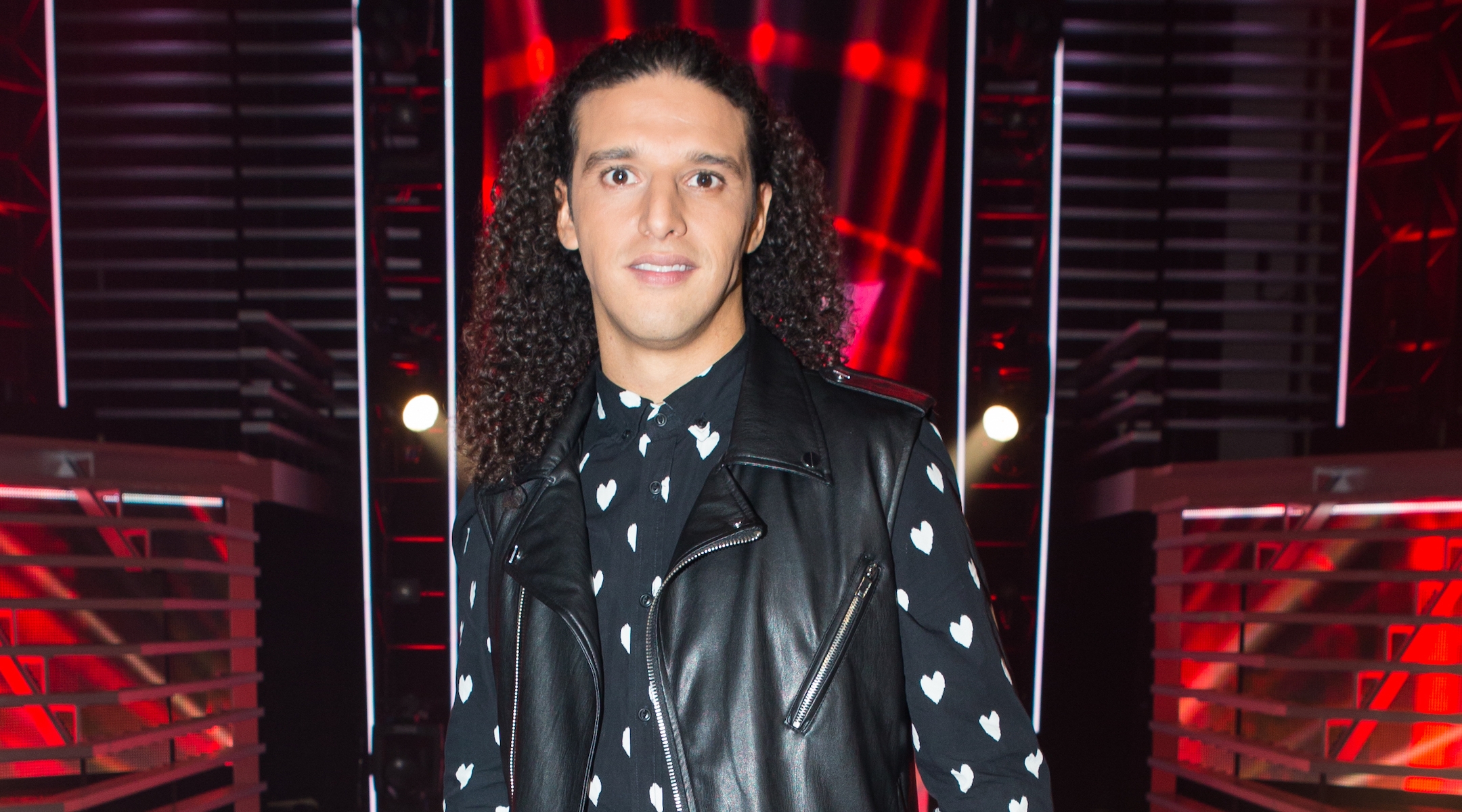

In the Netherlands, the celebrity rapper Ali B, who performed at the 2013 inauguration of King Willem-Alexander, released a single in 2017 featuring him singing that he “sits on money like a Jew” and “deports” greedy women.

The Dutch rapper Ali B attends the semifinals of “The Voice of Holland” in Hilversum, Dec. 13, 2013. (Helene Wiesenhaan/Getty Images)

Another Dutch rapper, Ismo, whose real name is Ismael Houllich, launched his musical career in 2014 with a single featuring the lyrics “I hate those f***ing Jews more than the Nazis,” “don’t shake hands with f***ots” and “don’t believe in anything but the Quran.”

Ismo was fined some $1,700 under Holland’s hate speech laws, but his conviction did little to curb his popularity. In fact, one of his singles made it to the top of the Dutch edition of the iTunes music platform for one week in 2015.

Far from apologizing, Ismo accused his critics of discriminating against him.

“They are trying to twist my words against me,” he said of his critics. “I don’t hate all Jews. I hate only Zionist Jews that made Palestine smaller than my neighborhood. They want to take every word that a Moroccan ever says and turn it into something anti-Semitic.”

Also in 2014, the Dutch Muslim rapper Hozny was given a suspended two-month prison sentence for threatening to murder the anti-Islam politician Geert Wilders.

But unaddressed during his trial were the anti-Semitic statements in the song about Wilders, including “As a soldier in Israel he was happy among the Jews/then hate for Islam was born in his eyes” and “How are things with your kippah? Are you being oppressed by the Jewish faith?” Wilders is not Jewish, nor has he served in Israel as a soldier.

In parallel to the so-called new anti-Semitism, in which Jews are targeted over Israel, the European rap scene is rich with Holocaust jokes and classical Jew hatred.

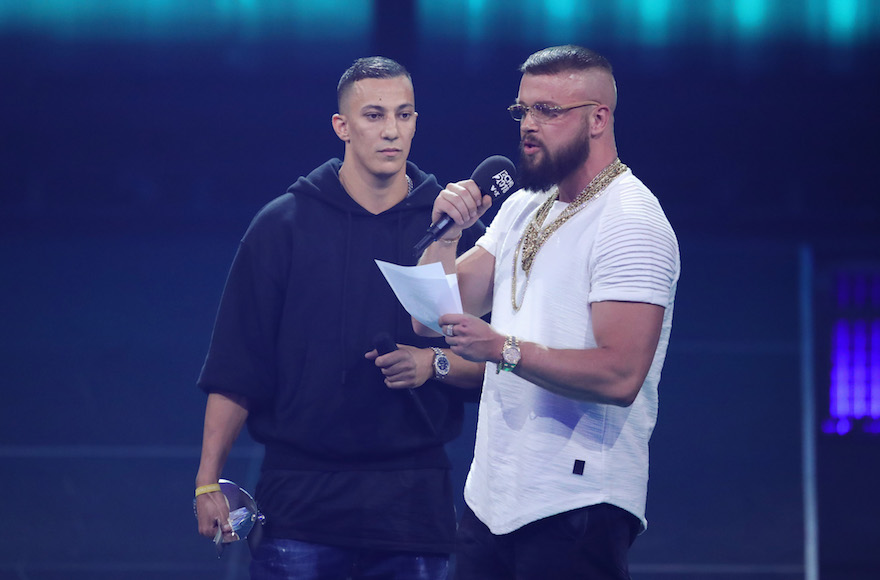

Last year’s Echo Awards ceremony — the German equivalent of the Grammys — was mired in controversy when the rap duo Kollegah and Farid Bang were honored for an album featuring a joke about their bodies being more “sculpted than an Auschwitz prisoner’s” among other Holocaust references.

Some activists against racism have started working with European rap artists precisely because of the scene’s anti-Semitism problem.

Farid Bang and Kollegah speak at the Echo Awards show in Berlin, April 12, 2018. (Andreas Rentz/Getty Images)

“There’s no other music being consumed in vulnerable neighborhoods,” said Serfaty, the rabbi from France. “It needs to be a tool for introducing content in favor of tolerance, in favor of France.”

In 2016, Serfaty teamed with the French Muslim rapper Coco TKT. While Coco was in jail, the duo produced three clips extolling the virtues of tolerance, including one in memory of Ilan Halimi, a French Jew murdered in 2006 by anti-Semites.

The partnership helped Coco obtain an early release, but he landed back in jail after committing a robbery, Serfaty said.

“I think it was a matter of opportunism to get out,” Serfaty said of their collaboration.

Still, Serfati insists that his clips with Coco made some impact, and that rap is more than a cesspool of violent and racist texts.

“There is beautiful poetry and messages of unity in the genre,” Serfati said. “We need to encourage it, help it grow, not overnight but over time.”

The German rapper Salomo is also doing his part. Born in Israel, the 41-year-old musician moved with his parents to Berlin when he was 4. Some of his songs introduce a rare counternarrative to the German rap scene, including “You Tell Me,” a single released on Jan. 27, International Holocaust Day.

“People ignore warnings when Nazis are on the march/you tell me: Get used to it/when migrants continue to radicalize and multiply the hatred/but I won’t stand for your false tolerance,” he sings, adding “Germany, what is happening to you?”

It has received nearly 80,000 views on YouTube and was widely discussed in the media.

Eclipsed at times by rap scene racism, “people rap about clothes, animals, food, world peace, their love for music, their moms, their dads or their role as fathers,” said Heidi Süß, a scholar who researches rap at the University of Hildesheim, Germany.

Many rappers visit schools as part of political education projects and intercultural activities, she added.

“There are numerous efforts to promote tolerance, love and solidarity through rap,” she said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.