(JTA) — At first glance, Bram Presser looks more like a punk rocker than a sensitive novelist. He has two big lip piercings, a few scraggly dreadlocks and a quirky beard only under his chin line.

And, yes, Presser, 43, was the lead singer and songwriter of Yidcore, an Australian punk rock band that achieved considerable success in the early 2000s with its covers of Jewish songs — such as the entire score of “Fiddler on the Roof” — and original compositions.

Yet this very same dude wrote “The Book of Dirt,” a thoughtful, lyrical examination of his family’s Holocaust past. It begins with a warning: “Almost everyone you care about in this book is dead.” But as the Jewish Book Council noted last month when it awarded Presser its Goldberg Prize for Debut Fiction, the book is “so beautifully executed that it authenticates the voices Presser seeks to awaken.”

Those are the voices of his family, starting with his grandfather, Jan Randa, who like many survivors didn’t talk about his wartime experiences. Still, Bram writes, “the nightmares had a way of sneaking out, just like the screams [that] kept my mother awake throughout her childhood.”

“He absolutely did not want to transmit the trauma he went through,” Presser said in a phone interview from his home in Melbourne.

His grandfather, who later went by Jacob Rand, spoke about his experiences exactly twice. The first time it was on Yom Hashoah at a Melbourne Jewish school where he taught, and where the students were mesmerized by the manner in which he described even the smells of the camp. He spoke again at the bar mitzvah of Bram’s older brother for 45 minutes to a less receptive audience. He never discussed it again.

However, a reprint in the Australian Jewish News of an older article about Rand sparked Presser’s interest. It reported that Rand was part of the Talmudkommando, a select group of scholars assigned by the Nazis to evaluate the Jewish books and artifacts they stole. Supposedly the most valuable were to be included in the Museum of the Extinct Race, the Nazis’ planned “memorial” to the Jewish culture they hoped to erase.

“I didn’t really set out to write a book,” Presser said. “I wanted to find out what happened to my grandfather. I wanted go write about a boy from a small village in the Carpathian Mountains.”

The more he learned, the more fascinated Presser became by his family’s history. There was his great-grandmother, Frantiska Roubickova, a convert to Judaism, and grandmother, Dasa, a “mischlinge” (the Nazi term for someone of mixed race) who married Rand. A host of real historical figures — from a prewar Czech president, Tomas Masaryk, to Rabbi Judah Loew, the Maharal of Prague, one of the leading rabbis of the region in the 16th century — are also part of this multi-generation story. It quickly became clear to Presser that he needed to create a fictional landscape for it all to work.

The last picture of Jacob Rand before “the hell into which he was cast … For most of the students, it would be their last photo ever.” Rand is at left, in the double-breasted suit. (Courtesy of Presser)

He spent years in research, making multiple trips to the Czech Republic, Israel, Poland, the United States and England, and he devoured “hundreds of books.”

The final product alternates between a mystical retelling of his family’s past and an account of Presser’s own research. Some of the sources he encounters along the way offer different accounts of the same events and stories, making Presser wary of his grandfather’s own words.

It also delves into some of Rand’s time spent in the Theresienstadt camp through the eyes of the slightly fictionalized character Jakub R.

“The basic facts had to be right, to give a sense of what it was like to live under the occupation, to live in the camps,” Presser said. “These were people who had lives. They had friendships. They had close calls.”

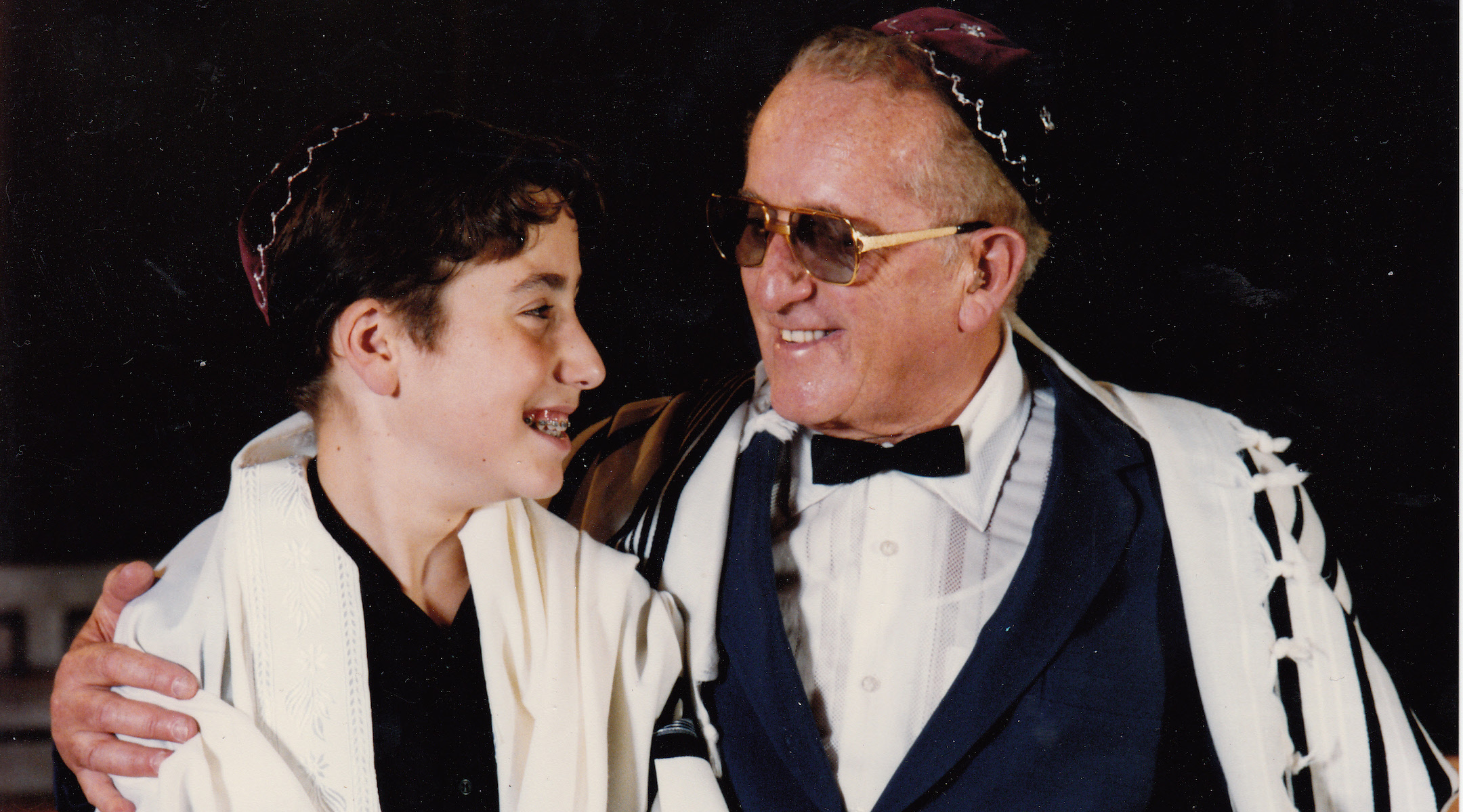

Bram Presser at his bar mitzvah with his grandfather. (Courtesy of Presser)

If writing “The Book of Dirt” was bashert — “fated” with Presser’s chance discovery of an article about his grandfather — so was his entry into the Jewish punk world.

“It was sort of by accident,” he said. “I was always kind of into heavy metal. In high school I was in an alternative rock band and we continued to play in college for the Jewish Student Union. We thought it would be funny to do punk versions of popular songs and lounge versions of punk songs. We did ‘Yerushalayim Shel Zahav,’ a big campfire song back in the day, and everyone loved it.

“Someone in the audience recorded a couple of songs and got it to a record executive who asked us to come in and record. We didn’t think much of it. We just did it for fun. It was a ridiculous joke that just went very well.”

The group developed a significant following in Australia, appeared on TV and filmed several videos. While they played festivals in America, “it was a lot more fringe, although we played one of the great venues, CBGB.”

Jewish punk was not universally admired.

“We were [mentioned] on neo-Nazi forums. They were talking about us a lot. There were lots of threats made, but no one ever showed up,” Presser said.

But the group was warmly embraced by the punk scene.

“They actively spoke up for us and protected us,” Presser said.

The group stayed together for about 10 years.

“We’d made all the Jewish jokes we could, done all the music, we were kind of done with that. Also the guitarist and I, we were the original members from beginning to end, and we agreed that if one of us wants to stop, we’d stop,” Presser said. “He got married and his wife was pregnant, so we got to retire rather than be retired. There’s something sad about 45-year-old guys playing shows.”

Fortunately, Presser had a fall-back plan. For 10 years he attended classes to earn his law degree — he held a university record for the longest time it took to acquire a degree without failing a course. It was comical: At one point he got a teaching assistant position and later joined the school’s staff, in some cases attending classes alongside students he taught.

It was an easy transition for Presser — but not so much for some judges.

“A judge would call a case and I’d stand up and introduce myself. And I’d say, ‘No, the client is the personable person behind me in the suit.’ That probably went on for the first year,” he said.

These days he’s living the life of a Jewish family man. Presser and his partner have a young daughter, and he continues to write (he’s concurrently working on two books, one he calls a “fable” of sorts). He’s also still busy promoting “The Book of Dirt,” which was published last fall, while on leave from his law firm.

“When you spend eight years on a book, you have no idea how it will do,” he said. “You’re just happy that someone reads it.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.