KANSAS CITY, Mo. (JTA) – The scribbled, shorthand note is faded, but the formal origins of the first modern Jewish state are clear: “H(is) M(ajesty’s) G(overnment) accepts the principle that P(alestine) shld. reconstitute as the Natl. Home of the J(ewish) P(eople) …”

Jotted on stationery from London’s Imperial Hotel, the memo would be forwarded along with a second annotated version to Britain’s foreign secretary, Lord Arthur James Balfour, who would revise them into an official declaration on Nov. 2, 1917.

“Those are two amazing little pieces of paper,” said Doran Cart, senior curator at the National WWI Museum and Memorial here, where a revelatory new exhibit probes the century-altering impact of the Great War from a Jewish perspective. “To have them here is an incredible touchstone — not only for the Jewish community, but also for everyone else, because that has really affected the world order.”

Besides the original drafts of the Balfour Declaration, which was officially announced toward the end of the war, the exhibit titled “For Liberty: American Jewish Experience in WWI” offers a remarkable range of artifacts tracing Jewish responses to the war — from early enlistment to outspoken opposition to efforts to help other Jews around the globe.

Through dozens of photos, placards and personal correspondence, it explores the fortuities and challenges of American-Jewish identity and highlights the consequences of century-old events — from Balfour to the Bolshevik Revolution, also in 1917 — that still reverberate today.

Even as it marks the centennial of its ending this year, the first world war is often overlooked in comparison to the one that came after — though not so much in Kansas City, where the museum’s 265-foot-high Liberty Memorial rises above downtown. The site was dedicated in 1921 in front of more than 100,000 people, including the Great War’s five Allied commanders. More than 150,000 showed up when President Calvin Coolidge opened the tower to the public five years later.

In the 1990s, the tower was restored and significantly expanded with the world’s most diverse collection of artifacts from the war. Congress declared it the nation’s official WWI museum in 2004.

Also overlooked — or rather underknown — is the outsize impact World War I had on Jewish Americans, many of them only recently arrived in the country. Of the 4.8 million men and women who would serve in the American Expeditionary Force, 250,000 were Jews.

World War I Jewish soldier William Shemin’s Medal of Honor framed with certificate, 2015. (Courtesy of Elsie Shemin-Roth)

“When the time came to serve their country under arms, no class of people served with more patriotism or with higher motives than the young Jews who volunteered or were drafted and who went overseas with our other young Americans,” Gen. John Pershing, commander of the expeditionary force, said in a 1926 address to an interfaith crowd in New York City.

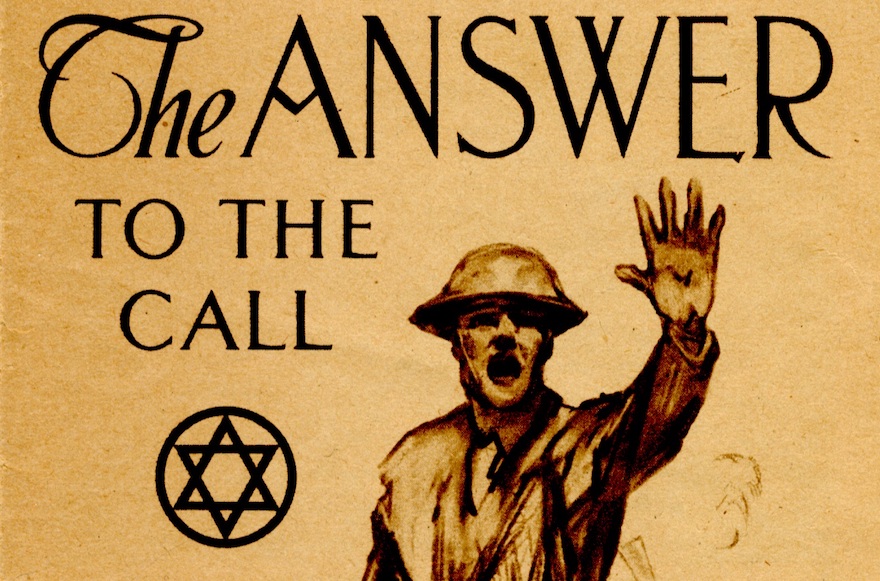

Indeed, “For Liberty” offers plenty of odes to Jewish commitment to the cause by those in uniform and beyond. The large recruitment posters printed by the Jewish Welfare Board may be the most eye-catching, as is the fully preserved uniform of Army Sgt. William Shemin — and the Medal of Honor he was awarded posthumously in 2015.

Also on display is songwriter Irving Berlin’s draft card, as well as copies of the patriotic music he wrote while stationed at Camp Upton on Long Island, New York. In addition, here’s the score from “Jewish War Brides,” written by Boris Thomashefsky — one of several Yiddish Theatre productions staged in support of the war. A photo shows the Jewish singer and vaudevillian Nora Bayes belting out the first recording of George M. Cohan’s “Over There,” which was to become the best-selling anthem of the war.

Yet the exhibit is also alarming, in a cautionary tale sort of way. Rabbi Stephen S. Wise’s 1917 New York Times op-ed declaring that American military service will “mark the burial … of hyphenism, and will token the birth of a united and indivisible country,” is presented as a dream clearly still unrealized.

Other documents, such as letters from politicians to American Jewish leaders requesting loyalty oaths, notices demanding “100% Americanism” and a cartoon depicting a literal wall to keep out “alien undesirables” echo the anti-immigrant passions and policies of today. The Communist revolution quickly led to the earliest Red Scare and fears of Russian influence in America — though after centuries of life under the czars, it was seen as “deliverance” by many Russian Jews and their American relations, as revealed by a special Haggadah supplement published to celebrate this newest exodus.

Photos and quotes highlight the anti-draft activism of Emma Goldman, who was arrested and eventually deported with hundreds of other “radical aliens” for “anarchism.” There’s also the hint of a Supreme Court controversy, symbolized in the robes of the first Jewish justice, Louis Brandeis, whose 1917 appointment and contentious, months-long confirmation process was seen as unprecedented.

The National WWI Museum and Memorial opened to the public in 1926. (Courtesy of The National WWI Museum and Memorial)

“For Liberty” is especially prescient considering that it was planned years ago. A joint effort of Philadelphia’s National Museum of American Jewish History and the American Jewish Historical Society in New York, it debuted at those two institutions last year under a different name.

Rachel Lithgow, then-executive director of the historical society, wanted the exhibit to travel beyond the Jewish-museum world, so that visitors of different backgrounds could see it.

“I wanted any hyphenated Americans to be able to relate to it because the Jewish story [of that time] is the Italian story, it’s the Irish story, it’s the Asian story,” she said, noting that 18 percent of the American Expeditionary Force was foreign-born. “It’s really, how did people become American, what does becoming American look like?”

Cart, the museum’s senior curator, said he was intrigued when Lithgow presented the idea.

“It told a new story, that we had dealt with in smaller ways, but never in a real comprehensive exhibition like this,” he said.

The local community, home to nearly 20,000 Jews, has shown substantial interest in the exhibit. A capacity crowd attended a July presentation at the museum on the attitudes of American Jews toward the war featuring Michael Neiberg, a professor of history at the U.S. Army War College.

On a recent Monday evening, nearly 200 members of the Women’s Philanthropy of the Kansas City Jewish Federation gathered at the museum for the group’s annual meeting. Cart presented a PowerPoint on “American Jewish Women in World War I,” concluding with a series of slides from the museum’s archives: six typewritten pages of women volunteers of the Jewish Welfare Board who had traveled overseas in the war’s waning days.

As the lists of names went up, many in the crowd gasped.

“You could hear excited mumbling throughout the room,” recalled Barb Kovacs, a business consultant who had just been installed as Women’s Philanthropy board chair. “’That’s my last name.’ ‘That’s my maiden name.’ ‘That’s my grandmother’s maiden name.’ It brought it home and made it really personal.”

The show continues through Nov. 11 — Veterans Day and the 100th anniversary of the armistice that ended the Great War.

While Lithgow has moved on from the American Jewish Historical Society — she is now executive vice president for Beit Hatfutsot International — she expects the exhibit she co-created will have a future.

Kovacs hopes so, too.

“In Kansas City — and wherever it travels — for people to have access to this information is so important,” she said. “It set the stage for our own story.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.