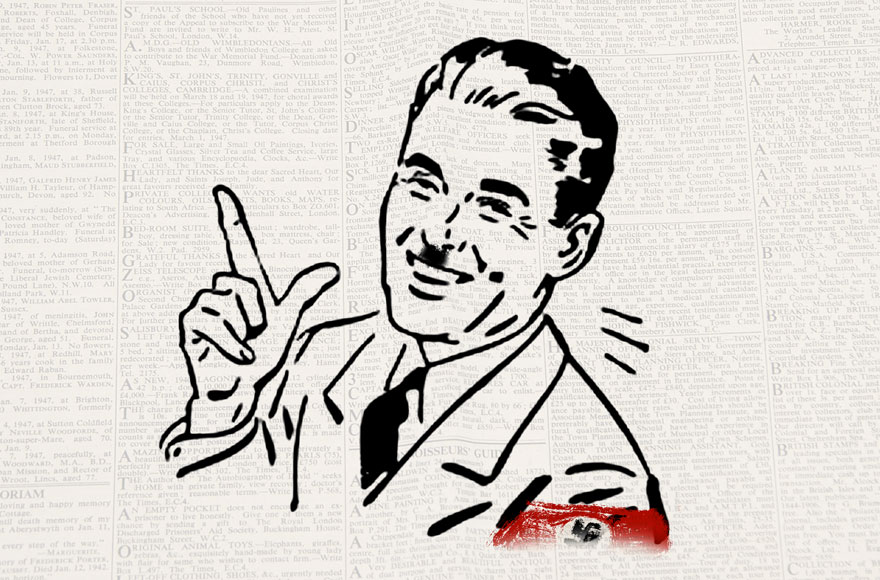

NEW YORK (JTA) — Did The New York Times just normalize an American neo-Nazi?

That’s the charge being flung at The Newspaper of Record over its Saturday profile of Tony Hovater, 29, a “polite,” “low key” Ohio man and “committed foot soldier” who helped start one of the white nationalist groups that marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August. The article, titled “In America’s Heartland, the Nazi Sympathizer Next Door,” depicts Hovater cooking pasta for his sympathetic wife and pushing a shopping cart through his local grocery, and asserts that “his Midwestern manners would please anyone’s mother.”

A lot of readers were outraged, saying the article by Richard Fausset humanized a racist who deserves only scorn and made a “man who believes the races should be separated seem likable.” The Washington Post’s Karen Attiah complained that The Times “thought it was okay to give prominent space to Nazi ideology.”

The criticism moved Marc Lacey, the newspaper’s national editor, to write an editor’s memo.

“We regret the degree to which the piece offended so many readers,” he wrote.

But Lacey also defended the intention of the piece.

“The point of the story,” he wrote, “was not to normalize anything but to describe the degree to which hate and extremism have become far more normal in American life than many of us want to think.”

And that is how I read the piece — the first time. To me it was an attempt to understand the tiki torch-carrying thugs who marched in Charlottesville and a useful reminder that not every racist or Nazi sympathizer shaves his head, wears jackboots or waves the Confederate battle flag.

Fausset, the writer, insists as much in the article itself. Here’s what journalists call the “nut graf” — or English teachers might call the thesis statement:

He is the Nazi sympathizer next door, polite and low-key at a time the old boundaries of accepted political activity can seem alarmingly in flux. Most Americans would be disgusted and baffled by his casually approving remarks about Hitler, disdain for democracy and belief that the races are better off separate. But his tattoos are innocuous pop-culture references: a slice of cherry pie adorns one arm, a homage to the TV show “Twin Peaks.” He says he prefers to spread the gospel of white nationalism with satire. He is a big “Seinfeld” fan.

I applaud Fausset’s attempt to understand how noxious beliefs have infiltrated suburbia, and how the politics of white resentment have breathed new life into the repugnant philosophies of Nazism and institutionalized racism. I get the irony when Fausset describes Hovater’s “Midwestern manners,” and I think he provides an important service when he warns how the “alt-right” movement is hoping to make white supremacism and anti-Semitism “less than shocking for the ‘normies,’ or normal people.”

That’s a lesson that needs to be heard, especially in the White House, where the president once spoke about the “very fine people” on the side of those nicely dressed young men seeking the separation of the races.

But how you read the article will depend on your interpretation of the word “But” that begins the third sentence in the excerpt above. I initially read it as “he may have his homey tattoos and ‘Seinfeld’ references, but this guy is a thug.” But I now see how many read it as “he may sound repugnant, but he is actually a nice guy with some upsetting ideas.”

Some of the blame for that interpretation falls on Fausset. Too often he relays one of Hovator’s “uglier” ideas without explaining why they are vile, as when Hovator is shown “defending his assertion that Jews run the worlds of finance and the media, and ‘appear to be working more in line with their own interests than everybody else’s.'”

Fausset doesn’t comment on these assertions — presumably because the reporter feels that readers will need no reminder how awful they are. But maybe that presumption no longer holds. Maybe we need a sentence or outside source saying something like this: “Those kinds of conspiracy theories are at the heart of Western anti-Semitism, and formed the basis for the ideology, revered by Hovater, that justified the systematic slaughter of 6 million people.”

It’s not clear if Fausset directly challenged Hovater with the history of anti-Semitism, genocide or Jim Crow. But he does say that he asked why Hovater “moved so far right.” The term “far right” in this context unfortunately puts genocide and racism on a continuum with other right-wing ideas, as if they are just slightly more extreme than lower taxes and fewer regulations. That’s where readers rightly sense the “normalization” of the fascist fringe.

Again, Fausset repeatedly shows Hovater at his worst, whether he is paraphrasing a Nazi slogan or sharing a social media post that imagines the Aryan paradise Germany would have become had it won the war. But the article’s best intentions come crashing down with this:

[Hovater] declared the widely accepted estimate that six million Jews died in the Holocaust “overblown.” He said that while the Nazi leader Heinrich Himmler wanted to exterminate groups like Slavs and homosexuals, Hitler “was a lot more kind of chill on those subjects.”

“Widely accepted estimate”? How about the “the historians’ consensus” or “the overwhelming evidence”?

And if Hovater is going to assert something as preposterous as the notion that Hitler was “chill” about genocide and ethnic cleansing, Fausset should immediately have quoted an actual historian saying how central to his policies were the elimination of Jews and other “undesirables.”

I’ve often argued that the strength and weakness of The Times is that it often acts as if it is having an “insider” conversation with the kinds of readers who form its core, or idealized, audience: liberals, the affluent, the highly educated and, yes, Jews. That assumption leads to highly critical Israel coverage, for example, because this is the way “family” talks with one another.

In this case, it led editors to assume that readers would read a portrait of a neo-Nazi “normie” as a cautionary tale about the mainstreaming of hate. But it forgot about a wider audience that still needs a reminder that some ideas are not merely “ugly” but vile, abhorrent and fundamentally un-American.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.