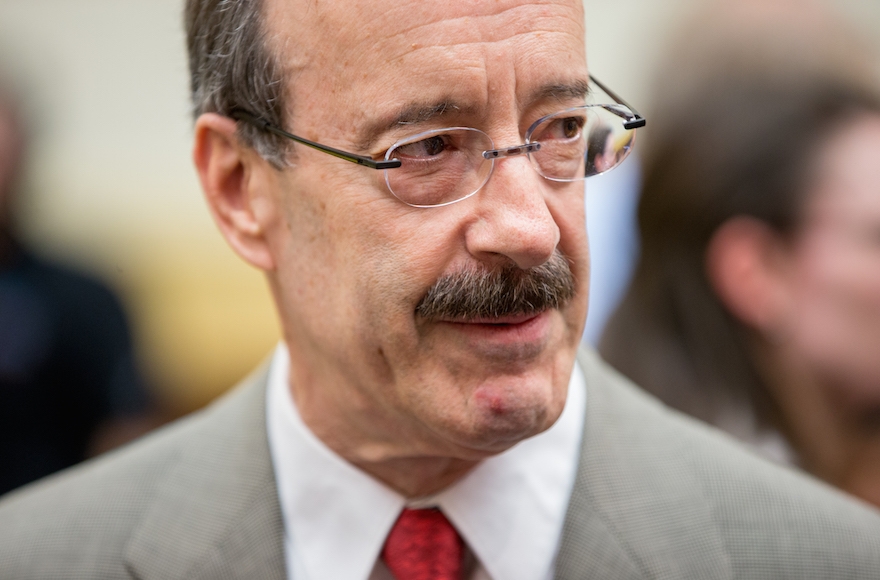

Rep. Eliot Engel, D-N.Y., the top Democrat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, knows from Jewish history. He also knows from Syrian history.

A leader of the (unofficial) congressional Jewish caucus, he is out and front on Jewish and pro-Israel issues. He also helped write the 2003 Syria Accountability Act, which isolated the Assad regime, in part because of its abuses of the rights of its citizens and of its neighbor Lebanon.

Engel melded both interests in a speech Wednesday at a joint meeting on foreign fighters convened by the Foreign Affairs and Homeland Security Committees, with a rhetorical device invoking the helplessness of Jews in 1938 as a measure of a real and present bias against Syrians. He used the casual locution “the other day” to lead into a powerful punch, saying:

I look forward to a good conversation about what we do now. Because it’s up to us whether we will stand with our allies and partners and effectively confront an enemy, or allow fear and panic to make us forget who we are and what we stand for as a nation. And I’d like to say a bit about that, because I’m unsettled by what I’ve heard from some people in Congress this week.

I read a poll the other day. The question was quote, “What’s your attitude towards allowing political refugees to come into the US?” unquote. Sixty-seven point four agreed with the response, “With conditions as they are, we should try to keep them out.” More than two thirds. “Try to keep them out.”

That poll was conducted in the summer of 1938. And the question in its entirety was, “What’s your attitude towards allowing German, Austrian and other political refugees to come into the US?” European Jews. More than two-thirds of Americans thought we should just close the gates just four months before Kristallnacht.

And so less than a year later, that attitude sealed the fate of the men, women and children onboard the ocean liner St. Louis. Nearly a thousand refugees, most of them German Jews, boarded the ship with the hope of finding safety across the Atlantic. After being turned away in Cuba, those onboard the St. Louis turned their sights towards the United States. They came so close to Miami they could see the lights. Their cables to the White House and State Department begging for safe haven went unanswered. The St. Louis steamed back to Europe.

Six-hundred twenty passengers ended up back on the continent. 254 of them died in the Holocaust. Onboard the St. Louis, they had passed close enough to Miami to see the city’s lights.

Syrians are fleeing their homes because life in Syria for the last four years has meant not knowing when Assad will drop the next barrel bombs or release poison gas. It has meant watching community after community fall under the merciless and medieval rule of ISIS. Often with just the clothes on their backs, men, women and children are struggling to escape, not because they agree with terrorists, but because terrorists have destroyed their lives and staying behind could very well ensure their deaths.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.