(JTA) — When Barney Frank first ran for a seat in the Massachusetts legislature, he more closely resembled a rumpled guy who slept in his suits than a polished pol. His campaign poster featured a photo of Frank looking typically disheveled. The slogan: “Neatness isn’t everything.”

More recently, he prepared bumper stickers that read “Vote Democratic. We’re not perfect, but they’re nuts.” The “they’re” in this case meant Republicans, of course, particularly their Tea Party wing.

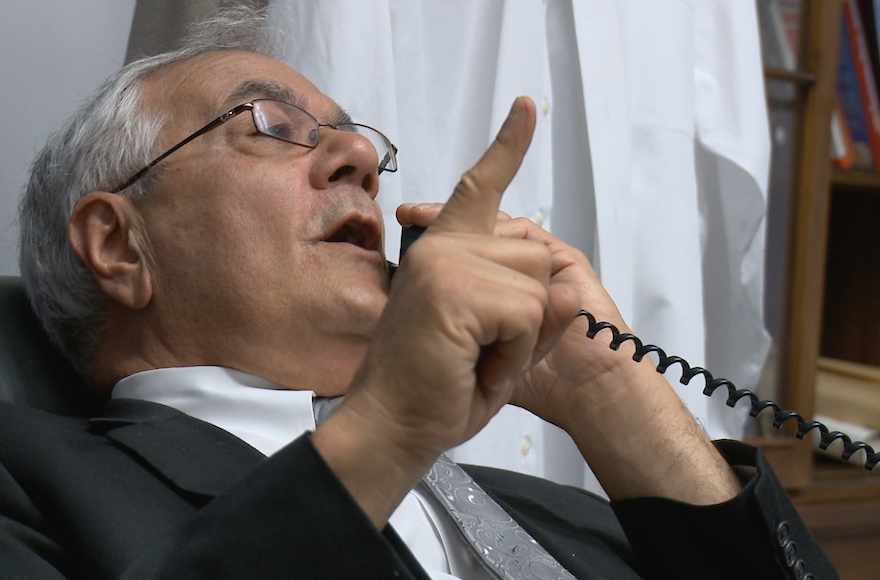

One of the delights of the documentary “Compared to What: The Improbable Journey of Barney Frank,” which premieres Oct. 23 on Showtime, is that it reveals this cheeky, irreverent side of a man better known for his pugnacious, doesn’t-suffer-fools-gladly style. Moreover, it shows him to be more a pragmatist than ideologue, willing to compromise and work across the aisle to pass legislation. It was that apparently rare ability that enabled him to get the 2010 financial reform bill passed — it was known as the Dodd-Frank Act.

Beyond Frank’s bluster and funny one-liners, however, the film is an affectionate, moving portrait of a good man. It makes excellent use of archival footage and fresh interviews to offer a balanced portrait of his 40-year career in public office, including 32 in the House of Representatives.

Frank, 75, announced his retirement in 2012. The decision, he says, was unrelated to the growing partisanship in Congress.

“I was just tired,” he told JTA as part of a wide-ranging interview. “I just didn’t have the energy.”

Frank says he has no regrets leaving office when he did. It freed him so that he no longer had “to pretend to be nice to people I don’t like.”

Still, Frank believes that had he stayed, he would have been effective despite the acrimonious climate.

“I was in Congress when Newt Gingrich was there, and I was tasked by the Democratic leadership to lead the fight against him on the floor,” he recalled. “It’s different because there’s more rhetoric and less legislating, because you’re in the fight for public opinion. It’s a different role, a less satisfying role. But one I’d feel comfortable in.”

READ: Philadelphia museum celebrates Jewish role in promoting gay rights

Frank offers a cure for what ails us: Cut military spending and eliminate the war on drugs. That, he claims, would “free $150 billion for health care and [low-cost rental] housing.”

His support for federal financing of multi-family residential rental housing — he doesn’t believe everyone needs to own a home — is one of the things he says he’s proudest of, though legislation he helped pass in the House was often killed in the Senate. He’s similarly proud of his efforts to establish LGBT rights.

Its something he’s embraced on a personal level: Frank married his partner Jim Ready in July 2012 in a ceremony officiated by then-Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick.

It’s nice to know that Frank got his happy ending, but what emerges in “Compared to What” is how the the earlier years of Frank’s career he felt forced to keep his sexual identity a secret, reflecting the attitudes of the time.

Frank realized he was gay when he was 13 growing up in Bayonne, New Jersey.

“It was a strong Jewish community,” he recalled. “Bayonne was about 10 percent Jewish. This was the ’40s and there was a lot of anti-Semitism, so the Jewish community tended to band together.

“My family wasn’t religious. We were very ethnic. But I went to Hebrew school and had a bar mitzvah. Growing up and going forward, I recognized a lot of Jewishness: in my taste in food, in my sense of humor and I do have a larger than normal number of Jewish friends than would be statistically expected.”

Barney Frank speaking at the Democratic National Convention in 2012. (Michael Chandler)

Frank settled in Boston as a student at Harvard, where he graduated in 1962. In 1967 he worked on mayoral candidate Kevin White’s first campaign — and was named chief of staff when the 38-year-old White won the election.

In 1972, still closeted, he won the first of four consecutive terms to the state legislature. In the late ’70s, with a new law degree from Harvard, he planned to come out, recognizing it meant the end of his political career. His plan was to serve one more term and go into private practice.

He started by telling close friends and family he was gay. Then, in 1980, Pope John II ordered priests to withdraw from electoral politics and Father Robert Drinan, a Massachusetts congressman, complied and threw his support behind Frank — who won the seat he would hold for more than three decades.

Frank bowed to political reality and kept quiet until 1986, when he heard a soon-to-be published book was going to out him. First he told his mentor, the late House Speaker Tip O’Neill, who told him not to worry; rumors happen. When Frank told O’Neill that this time it was true, O’Neill was upset — he thought Frank would be the first Jewish speaker.

But Frank’s public reveal didn’t hurt him in the polls. Neither did his involvement, while still closeted, with a male hustler that led to a reprimand, the most minor of all disciplines Congress can impose on a sitting member. He continued to win elections by margins so impressive that six times, the Republicans didn’t even bother putting up a candidate.

READ: A new documentary looks at the life of writer-AIDS activist Larry Kramer, warts and all

Throughout his tenure, Frank was a strong supporter of stricter environmental laws, of Israel and civil rights. Asked if the Jewish concept of tikkun olam motivated him, he responded, “I don’t know that. I do think Jews statistically tend to be more liberal and more concerned with repairing the world. I don’t remember saying I’m Jewish and I have to do this.

“I don’t think about why I’m doing something, just if it’s right. Though I guess if you’re a person who has been the object of prejudice, it will make you angry about it.”

So it might be surprising that Frank has spoken out against a fellow progressive and Jew — and one he’s been mistaken for at times: Bernie Sanders, whom he’s urged to withdraw from the presidential race.

“You absolutely shouldn’t be surprised by my view, given that I am for taking the most liberal position you can win on,” he said. “Sanders cannot win the presidency.

“I don’t think having an intra-party fight is helpful. I want to win the presidency. I want a Democratic president to appoint the next Supreme Court justices. I want the Democratic president to support health care. We’re fighting Republicans now, saying how dare you call the president [Obama] a socialist. There isn’t the remotest chance of Sanders winning.”

In a lengthy conversation interrupted by several phone calls — he always called back in minutes — only one subject was off limits: his legacy.

“That’s not for me to say,” he says. “Talking about it you come off arrogant or overly modest.”

Thankfully, the “Compared to What” does it for him.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.