This article was produced as part of JTA’s Teen Journalism Fellowship, a program that works with Jewish teens around the world to report on issues that affect their lives.

For the past 643 consecutive days (and counting), Eden Agulnik has devoted 10 minutes a day to the language learning app Duolingo. On her phone or computer, Agulnik, a high school senior in Toronto, translates sentences from English to Hebrew, matches new Hebrew vocabulary to English words and practices verb conjugations.

“I’m on a high daily streak, and just want to finish” the course, said Agulnik, who is on unit nine of 28.

Agulnik first downloaded the app as a way to supplement the Hebrew instruction she received at her Jewish day school. She is one of the more than 1.7 million other people who use Duolingo to learn Hebrew — including around 100,000 teens under the age of 18, according to a Duolingo spokesperson. Agulnik, like the other teens JTA spoke to, uses Duolingo not to start Hebrew learning from scratch, but rather to improve on existing knowledge from synagogue, Hebrew school or home.

Duolingo’s popularity — and debates surrounding its effectiveness — can partly be attributed to its gamified approach to language learning: Users earn “XP” (experience points) for completing lessons under a certain time; are ranked on competitive leaderboards, called “leagues,” based on the number of lessons they complete, and accumulate “streaks” when they complete lessons over many consecutive days.

For Agulnik and other teens who use Duolingo or similar language learning apps including Babbel and Rosetta Stone, these features can help ensure commitment. But the overall appeal of these language apps is that they offer a free, readily accessible way to engage with Hebrew when their school or synagogue doesn’t offer enough instruction.

Beatrice Olivetti attended a private Jewish day school in Turin, Italy through elementary and middle school, but is now a student at a public high school that doesn’t have a Hebrew language program. Before turning to Duolingo, Olivetti explored several options.

“At first, I joined a group of adults in the Jewish community in Turin, which didn’t work for me because that wasn’t right for a 14-year-old girl, “said Olivetti. “Afterwards, I tried online lessons for teenagers all around Italy. But the problem there was that we all had different levels.”

Olivetti has now been using Duolingo for two years, though as a self-described “lazy” user, she has not kept up a streak. And while she doesn’t believe it’s as effective as more traditional lessons, she has found it helpful.

“I don’t know about improvements, but I’m not afraid of losing my knowledge of the language as I was two or three years ago,” said Olivetti.

The Pittsburgh-based Duolingo has published several studies on the efficacy of its program, and claims that five units on Duolingo French or Duolingo Spanish is roughly equivalent to the same amount of semesters of university language instruction.

However, Or Rogovin, a professor of Hebrew at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, doubts that the same can be said of the Duolingo Hebrew course, in particular because the course offers very little explicit grammatical explanations.

“Duolingo and other programs were not developed for Hebrew, they started with Spanish. And what works well for Spanish doesn’t work well for Hebrew,” said Rogovin. “Hebrew grammar is so different [from] English grammar or Spanish grammar — it’s so different conceptually — that there’s no way to acquire Hebrew without an actual grammatical explanation. This does not mean that you can’t study it online, but you can’t do it on Duolingo.”

But other Hebrew educators see it differently. As the director of the Modern Hebrew Language Program at the University of Pennsylvania, Joseph Benatov supports the use of Duolingo, and other similar online resources, as one part of a more extensive curriculum, such as the one he has built for his college students.

“We have a combination of quizzes, longer, more traditional exams [and also] various sorts of more modern assignments, where students need to either create a TikTok or something else that has to do with social media, but in Hebrew — so it’s very varied,” said Benatov.

And though Duolingo is the most popular language learning app worldwide, according to Statista, it’s not the only resource teens are using for Hebrew education.

On YouTube, the Piece of Hebrew channel has around 40,000 subscribers. Co-creator Doron Shafat noticed while teaching on iTalk — a virtual language tutoring platform — that students often struggled with less formal, more conversational Hebrew. In 2020, Doron began uploading videos in Hebrew designed to help intermediate learners.

“I try to give [viewers] insight into specific words or phrases they need to know, and about Israeli culture. There can be things that are obvious to me as an Israeli, but I know they’re not obvious to an American,” said Shafat.

Thanks to the rise of Duolingo, iTalk and Hebrew-learning YouTube channels, Doron now believes that it’s possible to learn Hebrew independently, even without formal instruction or immersion in a Hebrew-speaking environment.

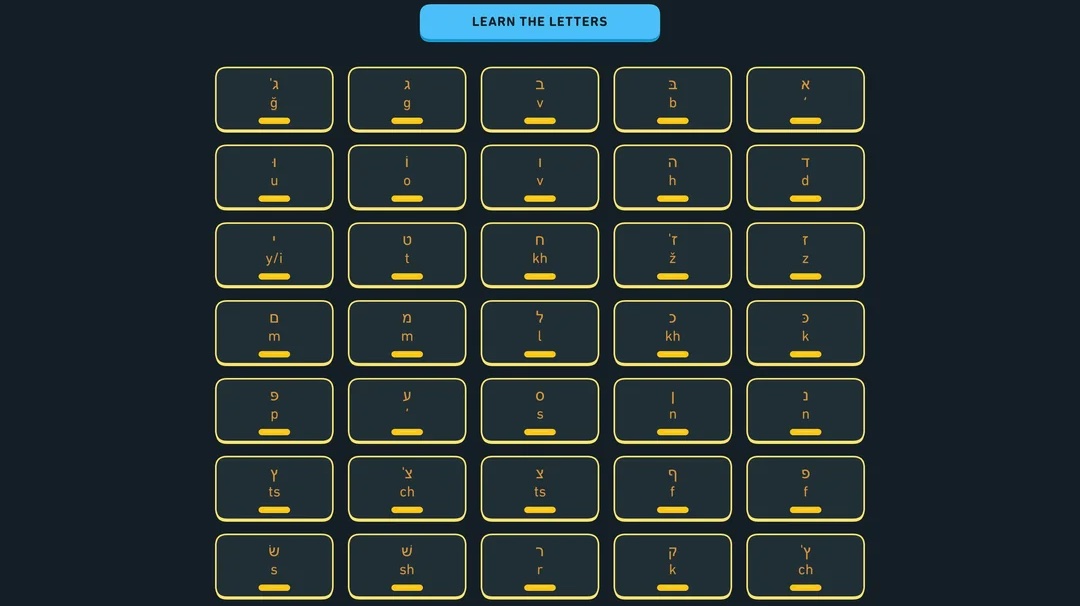

Duolingo’s Hebrew-language app begins with a lesson on learning the Hebrew alphabet. Above, a partial screen grab of a lesson page. (Duolingo)

“It is much more possible in comparison to the past, because nowadays you have an enormous quantity of resources to learn — and I think that’s the most important thing. To [learn] a language is to consume as much content as possible, even if you don’t get or understand the entire message,” said Doron.

Doron has noticed two main types of people interested in his content and other online resources for learning Hebrew.

“It’s either Jews that have connections to Israel, or have family in Israel, or they want to do aliyah, or they already did aliyah — that’s the biggest group,” said Doron, using the Hebrew term for immigrating to Israel. “The second group is people who are not Jews, but have affection to Israel or to Judaism for cultural reasons or for religious reasons — mainly Christians.”

A Duolingo spokesperson noted that the most common motivation for Duolingo Hebrew users, according to their survey, are “connecting with people,” “fun” and “school.”

Paulina Gamel, a senior at Northwest Yeshiva High School in Seattle, began learning Duolingo in part to prepare for a seminary program in Israel she plans on attending next year.

Gamel has Hebrew lessons in school, but has found that Duolingo can be even more effective for her than instruction in the classroom.

“I would say Duolingo [is more effective], just because I have a lot of distractions in class — I’m sitting next to my best friend and not doing Hebrew all the time. If you just sit down and do Duolingo for 30 minutes a day, you accomplish a lot. It’s [been] such an easy way to keep up my Hebrew skills, as well as improve it. It’s a simple thing, and it helps me remember to do Hebrew every day,” said Gamel.

One of the main reasons Gamel has persisted with Duolingo — she’s now on a 50-day streak — is to deepen her connection with Judaism.

“It really helps me because I personally say tefillah [prayers] every day. And the more I learn Hebrew, the more I’m able to like [understand] the words that I’m saying. I think that’s helped bring me close to Judaism,” she said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.