A museum holding one of the most important photography collections of pre-Holocaust Jewish life wanted to scan thousands of images and make them accessible to the public online.

As part of the fundraising to digitize the archive of the renowned Russian Jewish photographer Roman Vishniac, the museum, known as the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, applied in November for a $250,000 grant from a federal agency called the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

But last week the agency was effectively shuttered by the Trump administration, which called it “unnecessary” in an executive order signed by the president in March. The agency’s staff are on leave and its $290 million budget, most of which goes out as grants to museums and libraries throughout the country, is frozen.

The most significant consequence of the cuts is not the loss of any single grant opportunity: The Magnes, which is part of the University of California, Berkeley, is expecting to make up the difference through additional fundraising from private donors, according to executive director Hannah Weisman.

“The real concern is the ripple effect,” Weisman said. “If I don’t get a grant here from a federal agency, I’m going to go talk to a different donor who may already be talking to a peer of mine. It puts a strain on funding sources across the sector.”

The cuts go beyond museums. Virtually all federal grant-making for arts and culture is in jeopardy following recent and expected cuts across government agencies. The Trump administration on Thursday gutted the National Endowment for the Humanities. The National Endowment for the Arts is likely next, according to the American Alliance of Museums.

A comprehensive accounting is not available, but the impact on Jewish scholars, artists and cultural organizations is widespread:

- The San Francisco Jewish Film Festival and a related filmmaker residency could be downsized if NEA is shuttered as expected.

- An artist and printmaker announced that they lost NEH funding that would have allowed 25 students to spend their summer learning about the techniques and history of Jewish print culture.

- The Capital Jewish Museum says it was counting on federal funding opportunities as part of its efforts to collect and tell stories about Jews in the Washington, D.C. area.

- A Jewish theater organization is bracing for the potential cancellation of an NEA grant that would help fund its playwriting contest.

The harm of cuts to museums goes deeper than imperiling particular projects and plans, according to Christine Beresniova, executive director of the Council of American Jewish Museums.

“There could be a cascade effect from these kinds of drastic changes not only in terms of funding or staffing but in the latent message being delivered that museums are somehow not essential to the communities they serve — which they are,” Beresniova said. “These museums represent some of the only places in some communities where our communal rituals, values and identities are preserved and shared with both Jewish and non-Jewish groups.”

The Trump administration has justified its cuts as a cost-saving measure, but they are also happening against an ideological backdrop. Many conservatives believe that museums and other cultural institutions have come to focus too much on the faults of the United States and Western civilization.

An executive order last month, titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” articulated this criticism.

“Over the past decade, Americans have witnessed a concerted and widespread effort to rewrite our nation’s history, replacing objective facts with a distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth,” the executive order reads. “This revisionist movement seeks to undermine the remarkable achievements of the United States by casting its founding principles and historical milestones in a negative light.”

The order goes on to say that federally run parks and museums — and the Smithsonian in particular — must become “solemn and uplifting public monuments that remind Americans of our extraordinary heritage, consistent progress toward becoming a more perfect Union, and unmatched record of advancing liberty, prosperity, and human flourishing.”

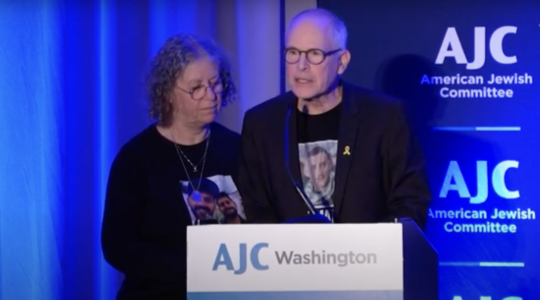

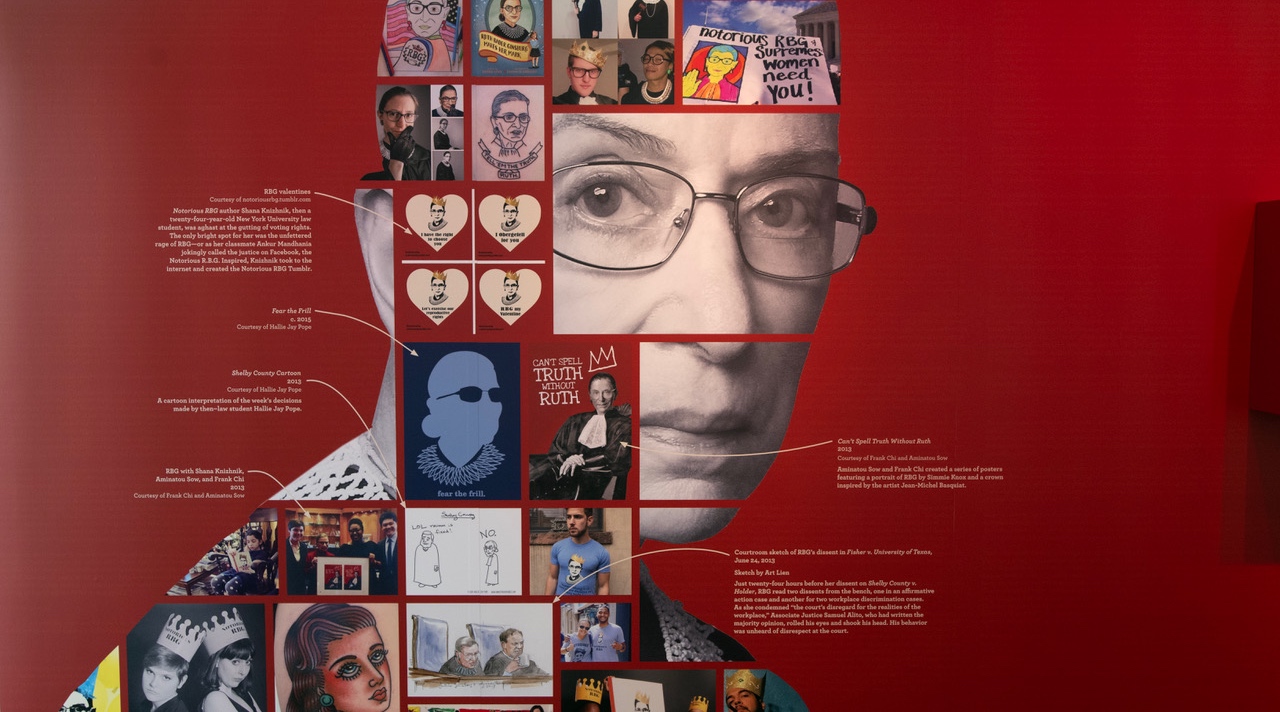

An exhibit on Ruth Bader Ginsburg at the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington D.C., June 1, 2023. (Ron Sachs/Consolidated News Photos)

The disappearance of federal support for private museums comes two years after the U.S. National Strategy to Combat Antisemitism, an initiative of the Biden White House, described museums as a critical tool against the spread of hatred.

The policy push led to a federal grant that paid for a national summit about how museums can combat antisemitism and for a guide for museum professionals. Held a few months after Oct. 7, 2023 amid a wave of antisemitism, the summit was called “Museums Respond.” Until the gutting of the IMLS, Beresniova was counting on the availability of federal funding to expand outreach and training.

“This content has to be amplified to take hold in the national consciousness, and federal support in this endeavor is vital,” she said.

Federal funding for cultural institutions isn’t just about dollars — it also serves as a powerful endorsement, fundraisers say. Receiving a government grant signals that an organization is doing important work, with clear plans, accountability measures, and oversight in place. It’s a vote of confidence that can unlock private donations, especially for small organizations with less fundraising infrastructure.

The disruption of that dynamic is worrying for Lou Cove, who runs CANVAS, a grant-making and advocacy organization dedicated to increasing Jewish philanthropic support for the arts. (The Jewish Telegraphic Agency is a brand of 70 Faces Media, which receives funding from CANVAS.)

“The loss of the imprimatur of federal funding is so almost as bad as losing the money because the Jewish philanthropic community already isn’t great about supporting the arts,” he said, estimating support at less than 1% of the Jewish philanthropic sector.

The reluctance stems in part, Cove said, from the feeling among many donors that they are not equipped to evaluate the impact of Jewish arts and culture organizations on their own. The problem is especially dire amid rising antisemitism and other issues regarded as existential, he said.

“Donors are saying, ‘The arts are a nice-to-have, but not a need-to-have in a moment of crisis like this,’” Cove said.

But even institutions that work explicitly on the crisis of antisemitism and don’t receive any money from the federal government are expecting fundraising to become more difficult as organizations affected by the cuts turn to donors to help.

The Tucson Jewish Museum & Holocaust Center is concerned, for example, about the viability of its annual donor-supported educators conference, which every year trains dozens of local teachers in Holocaust instruction.

“Organizations that have traditionally relied on government grants are going to be rushing into that philanthropic grant pool,” said Lori Shepherd, executive director of the Tucson museum. “We’re already seeing it, and it’s making it more challenging for those of us who relied on that support. So it’s a ripple effect that can be very challenging.”

If Shepherd is worried about the impact on her museum’s finances, she says that she and other museum leaders are aghast at what the cuts represent.

“We’re reeling from these — for lack of a better word — attacks,” she said. “We’re not able to focus yet on the long-term effects that are going to be true and lasting devastation. This is going to strip our communities of access to educational resources and ideas.”

She says she sees in recent events a repetition of the historical events about which her museum teaches.

“That’s not hyperbole. It feels calculated to create a society of people who are actively hostile to education, who are actively hostile to knowing and understanding the world. And once that’s embedded, it will be really hard for us to turn that page back,” she said.

Meanwhile, at a small organization called the Jewish Plays Project, the attitude is that whatever the perils of the day may be, the show must go on.

Last year, the group was approved for a $20,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to expand its marquee playwriting contest, a national endeavor to discover new Jewish play scripts and advance them to production in theaters around the country.

Staff at the NEA recently told the group’s founder and executive artistic director, David Winitsky, that the money will arrive as promised, and he’s already applied to renew the grant during the next funding cycle.

But he knows that the staff handling his grants could be out of their jobs at any moment and the money may never materialize. Still, he said he’s refusing to be pessimistic and vowed to continue making Jewish art with whatever support is available.

“I don’t want to be pollyannaish about it,” he said. “The most powerful government in the world really does want to control or limit art. I spend a lot of time talking to artists who are losing their minds about it. I tell them to keep calm and carry on. The world needs what we do.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.