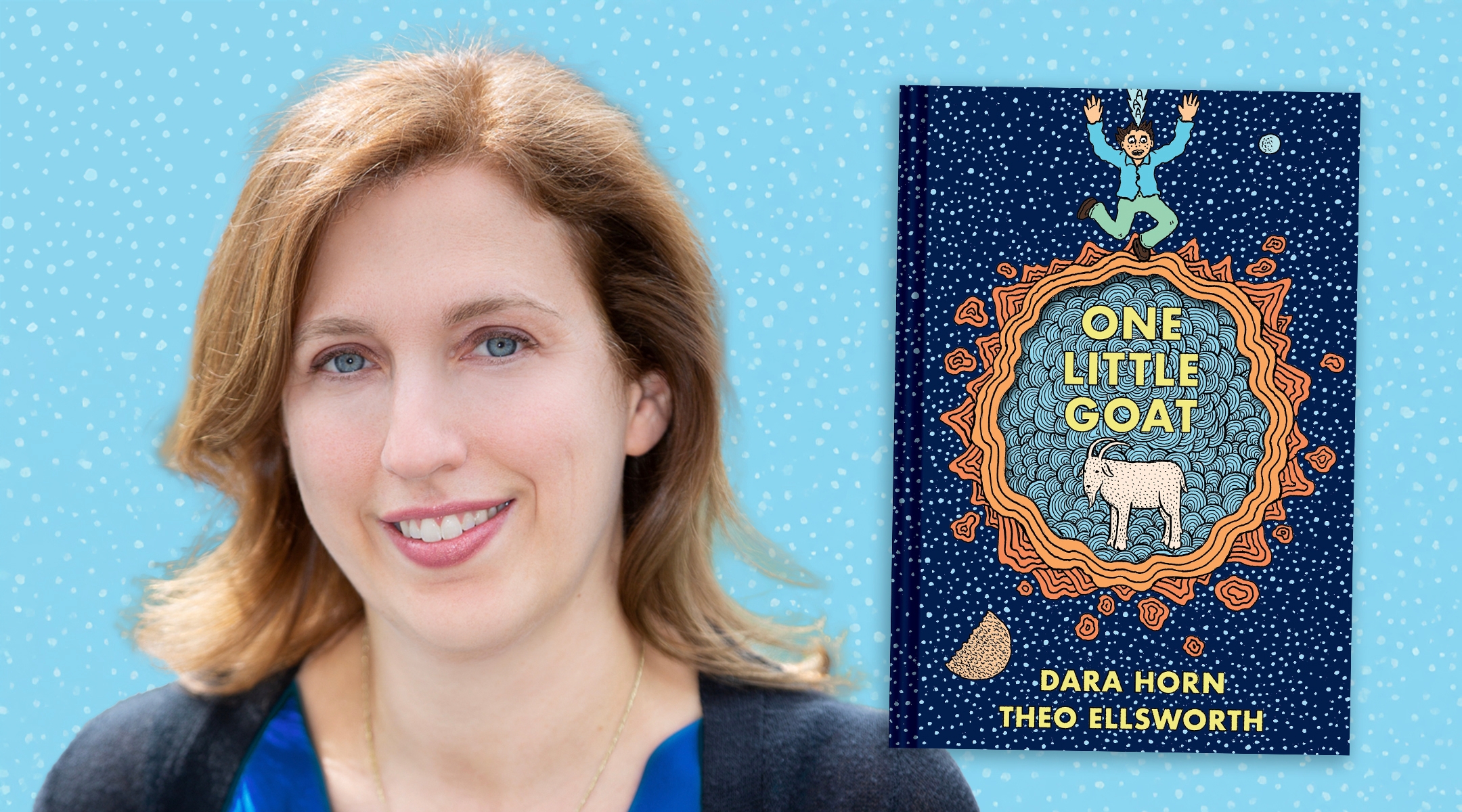

“All of my books are the same book,” said Dara Horn, the author of seven novels and the 2021 essay collection, “People Love Dead Jews,” which may be the most talked-about Jewish book of the past several years.

The subject, she said, is time — how Jews mark it, how they preserve it, how they understand where a moment goes once it is passed. Her 2006 debut, “A World to Come,” toggles between present-day New Jersey and 1920’s Russia. Her 2018 novel “Eternal Life,” meanwhile, is about an immortal woman, born in Jerusalem, who experiences countless lives over 2,000 years.

She took the title of her 2009 Civil War novel, “All Other Nights,” from the Passover Haggadah, which she calls a book about “the collapse of time,” expressed in its injunction that “in every generation a person is obligated to see themselves as if they left Egypt.”

It’s a verse that becomes literal in her latest book, the middle-grade graphic novel “One Little Goat: A Passover Catastrophe.” In it, a young boy escapes a seemingly endless family seder in the company of a talking goat, who drags him back through a “hole in interdimensional space-time” and to the seder tables of historically iconic Jews, including Sigmund Freud, the 16th-century philanthropist Doña Gracia Nasi and the Talmudic tag team known as Rav and Shmuel.

The book is both a history lesson, and a lesson about history.

“The seder is not just about the Exodus from Egypt. It’s also a commemoration of a commemoration of a commemoration,” said Horn, noting how the traditional Haggadah itself includes descriptions of at least two prior seders, the very first one in Egypt and one held in the Land of Israel after the destruction of the Second Temple. Quoting the late American historian Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Horn said Jewish culture makes a distinction between history and memory, and Jews are more interested in memory: investing a historical event with eternal, inheritable meaning.

“When I say I write about time, I mean specifically, how do we live as mortals in a world that outlasts us?” she said. “That’s the central question that I’m exploring as a writer.”

History and memory were the subjects of “People Love Dead Jews,” where Horn proposes that in its fascination with the ways Jews suffered and died, the world either overlooks or devalues the way they actually lived and live. Even well-meaning efforts like Holocaust-education mandates and Shoah memorials ignore the layers and layers of Jewish history and complexity, leaving Jews as convenient abstractions for antisemites and conspiracy theorists.

The conversation sparked by the book — “‘People Love Dead Jews’ ate my life,” she jokes — turned the novelist and Hebrew and Yiddish scholar into a go-to expert on the recent rise in antisemitism. An alumna of Harvard, she gave an interview to a Congressional committee as a member of Harvard’s Antisemitism Advisory Group, formed in the wake of Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel. In recent months she launched a nonprofit, Mosaic Persuasion, which aims to supplement Holocaust and history of religion units in K-12 education with curricula about the foundations of Jewish civilization and the causes of antisemitism.

“There are 29 states in this country where people are required by law to learn in school that Jews are people who were murdered,” she said, referring to Holocaust education mandates. “There’s not a single state in this country where anyone is required to learn, like, who are Jews? What’s Israel? What the hell do they have to do with the Middle East? We’ve outsourced that to TikTok.”

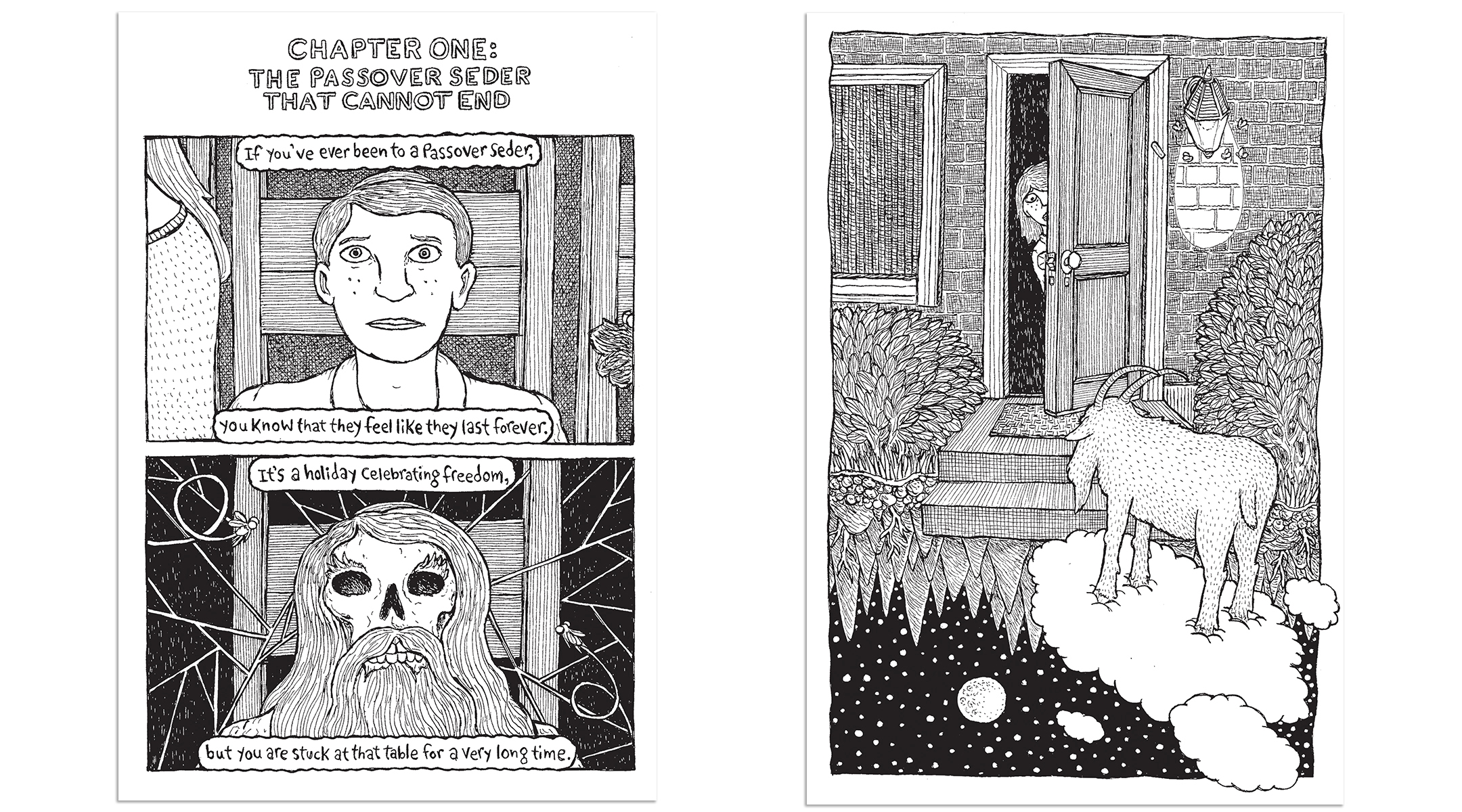

The art by Theo Ellsworth for “One Little Goat” lean into the dark themes of the Passover story, and the dry humor of Horn’s text. (Theo Ellsworth; Norton Young Readers)

“One Little Goat” appears to be adjacent to that project — helping middle-schoolers understand the way their own family history is an accumulation of Jewish lives and experiences reaching back through time and marked each year at the seder table.

The story was inspired by two seders that Horn, who was raised and still lives in Short Hills, New Jersey, grew up attending. At the first, hosted by her parents, Horn and her three siblings would perform songs and skits, riffing on pop culture. The second she describes as a “large multigenerational gathering” that included Holocaust survivors, including some who had participated in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on Passover of 1943, and former Soviet “refuseniks” were active in the Free Soviet Jewry movement.

Although frustrated that the kids played only a supporting role in the second seder, it left her with a kind of vision. “I felt like the room I was in was a lighted box that’s sitting on a tower of lighted boxes of other seders, including the seders that these people at this table have been at in the past,” she said.

The idea germinated for years before she contacted the decorated graphic novelist and illustrator Theo Ellsworth, a favorite of her children, and suggested they collaborate. Ellsworth, who is not Jewish, seemed to get it: If he wasn’t familiar with the Passover story, he understood its potential as a children’s adventure. Horn calls their book a “portal” story, like the Harry Potter books or C.S. Lewis’s Narnia tales, in which children slip through a passage into a fantastic world beyond.

“That’s so resonant for children because children’s lives are really small, and they’re completely managed by the adults in their lives,” said Horn. “That’s why children are looking for that access point to a life bigger than theirs.”

Horn said Ellsworth’s art — black and white, heavily inked, with an underground comics sensibility — appealed to her because it wasn’t “cute and cuddly.” Which raises the question: When are children ready to encounter a Jewish history of persecution and slaughter?

One answer is provided during the seder itself, which often ends with the traditional song “Chad Gadya,” or one little goat in Aramaic. It’s a “cumulative” song about a baby goat that is eaten by a cat, who’s killed by a dog, who’s beaten with a stick, culminating with the Angel of Death being slain by God. One interpretation is that the goat represents the Jewish people, and the climax of the song signals the redemption of the Jews. It’s a dark theme smuggled into an upbeat if macabre children’s song.

Making light of the seder’s darker themes is a Passover tradition all its own, and Horn is on board with it.

“By the time children are old enough to appreciate [the darkness], they own the story. They’re characters in the story, and they know that about themselves and that this is a story about us,” said Horn.

Horn embraces that darkness in her book, which includes an appearance or two by the Angel of Death. Horn recalls that the seder in the Torah is described as the Night of Watching. It takes place before the actual flight from Egypt, with the Jews at the table uncertain if they will survive.

“I can’t look at that scene anymore, of that first seder, without thinking of a ma’amad, the bomb shelters and safe rooms, where people in Israel were hiding on Oct. 7, and where everybody goes during missile attacks, where you’re hiding with your family trying to wait out the Angel of Death,” she said. “That’s where my mind was when we were finishing the book.”

Horn’s own seders are hardly grim affairs. She, her husband and four children stage extravaganzas, with a sort of Passover funhouse experience in the basement, laser lights and fog machines to simulate the parting of the Red Sea, and homemade movie and television parodies.

For Horn, Passover is a story about how Jews lived and how they survived. The history of persecution can’t be avoided but it is only part of the story.

Before “People Love Dead Jews,” said Horn, she would speak in bookstores about her novels and ask the audience two questions: How many people can name four concentration camps? And, how many people can name four Yiddish writers?

Most could answer the first question and few could answer the second.

“I’d say, ‘85% of the [Jews] killed in those concentration camps were Yiddish speakers. This is a very literary culture. Why do you care so much about how these people died when you really don’t care about how these people lived?’

“What I find really important about Jewish history is not this litany of horror — which I don’t think you can avoid talking about — but that the story of Jewish life is about this amazing creative resilience.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.