When Gal and Uzi Waizman opened a shop in their Los Angeles neighborhood that was solely devoted to bourekas, a stuffed pastry ubiquitous in their native Israel, they weren’t sure whether locals would go for them.

“The first day we made a batch and said, ‘OK, let’s see how this goes,’ and Uzi posted on his Instagram. He does not have thousands of followers,” Gal Waizman recalled. “And we sold out in 55 minutes.”

Soon, local TV crews arrived to film the lines of people snaking down Ventura Boulevard, waiting for their chance to buy a boureka from Bo.Re.Kas.

“It became a big hit overnight. It was really surprising,” Waizman said. “The beginning was crazy. People would wait an hour in line. We would open until we would sell out. We had a really small kitchen and we just couldn’t make enough.”

Today, the couple is on the verge of opening their third location, with ambitions of expanding beyond Los Angeles. And they count as old-timers at the leading edge of a bourekas trend that has reached the East Coast, with standalone bourekas shops opening recently in Connecticut and, this week, New York City. All of them are operated by Israeli immigrants who believe that the time is right for Americans to fall in love with their favorite fast food.

Burekas are “the slices of pizza of my childhood,” said Ben Siman Tov, one of the chefs behind Buba, opening Thursday in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. “It can function as a full meal but also a fantastic snack.”

The store laid out its concept in ads for kitchen staff: “We’re entirely focused on perfecting the bureka, a savory Mediterranean pastry served with briny pickles, crushed tomato, and a perfectly jammy egg.”

Over the weekend, Siman Tov and his collaborators — Breads Bakery’s Gadi Peleg and Fritz Oleshansky — opened Buba’s doors to friends, family and neighbors, jamming Bleecker Street with fans including the Jewish food personality Jake Cohen and the music producer Benny Blanco.

The invitees were crammed around the small tables set up in front of the store, sampling the various flavors: potato, spinach, cheese and corn — a new and unexpected filling that several guests announced as a favorite. Siman Tov’s wife, Zikki Siman Tov, circulated in the crowd, offering visitors a taste of the crunchy pickled vegetables that complemented the rich bourekas. (The couple co-byline a cookbook coming out this fall.)

Ben Siman Tov, who goes by BenGingi on Instagram, where he has more than half a million followers, got hooked up with Peleg after a chance meeting at the Union Square Greenmarket, the farmer’s market located adjacent to the original location of Breads, which Peleg owns and co-founded in 2013. Breads has sold bourekas from its first day in business, though the bakery’s babka has always outshone its savory offerings.

“We have always offered potato, feta and spinach feta,” said Peleg. “We’ve done others over the years, we have done different flavors, but those are the cornerstones. Mainstays. Every once in a while we play with it. But those are the crowd-pleasers.”

At first, his customers didn’t know what a boureka was — but he had a reliable strategy for introducing them. “When we first tried to explain to people, empanadas was a word that we used,” he said. “There is a similarity there. If you look back at the history of bourekas you will find that they originate from empanadas. That is their origin story.”

Bo.Re.Kas Sephardic Pastries started in an unassuming storefront in Sherman Oaks, California, but is soon to open its third Los Angeles-area location. (Philissa Cramer)

In fact, bourekas’ origin story reflects the complex paths of Jewish migration. The eminent Jewish food historian Gil Marks, in his “Encyclopedia of Jewish Food,” wrote that bourekas, as with most Jewish foods, are “a synthesis of cultures and styles; over the course of history, they have been transformed and transferred, on their way to becoming a ubiquitous treat in modern Israel.”

Food writers and historians agree that their name comes from the Turkish word börek, used to describe layered pastry squares still popular today. When Jews expelled from Spain in the 15th century arrived in the Ottoman Empire, they combined the flaky pastry of börek with the pocket structure of their own empanadas. The fusion food was popular across the empire, including in its northern reaches of Bulgaria — which, unusually, did not deport and murder its native Jews during the Holocaust. When 90% of the surviving Bulgarian Jews moved to Israel immediately after World War II, they brought bourekas with them.

Almost immediately, according to cookbook author Janna Gur, bourekas entered the elite echelon of Israeli street foods, “next to hummus, shakshuka and falafel.” She called bourekas “fascinating examples of the way Jewish immigrant foods made their way to the mainstream of Israeli gastronomy.”

Bourekas at the market in the central town of Ramle, July 30, 2024. (Yossi Aloni/Flash90)

Now, the food writer Vered Guttman says, bourekas are, in Israel, “the favorite staple in any gathering, from high-level Cabinet meetings to birthday parties and anything in between.”

Unlike hummus and shakshuka, bourekas have the advantage of being self-contained.

“The whole grab and go concept is big,” said the Jewish food doyenne Joan Nathan, who counts herself as a bourekas fan. (She particularly likes Chef Michael Solomonov’s versions.) “People are not necessarily cooking. People are looking for something new to write about, to eat, to have.”

As at Buba, the bourekas at Bo.Re.Kas Sephardic Kitchen — its full name a nod to the pastries’ history — are a labor of love. The massive sliced pastries are served, as they are in most shops in Israel that sell them, accompanied by an egg, grated tomato, schug (a Yemenite hot sauce) and pickles. All elements are made in house, from the pastry to the pickles and cheese.

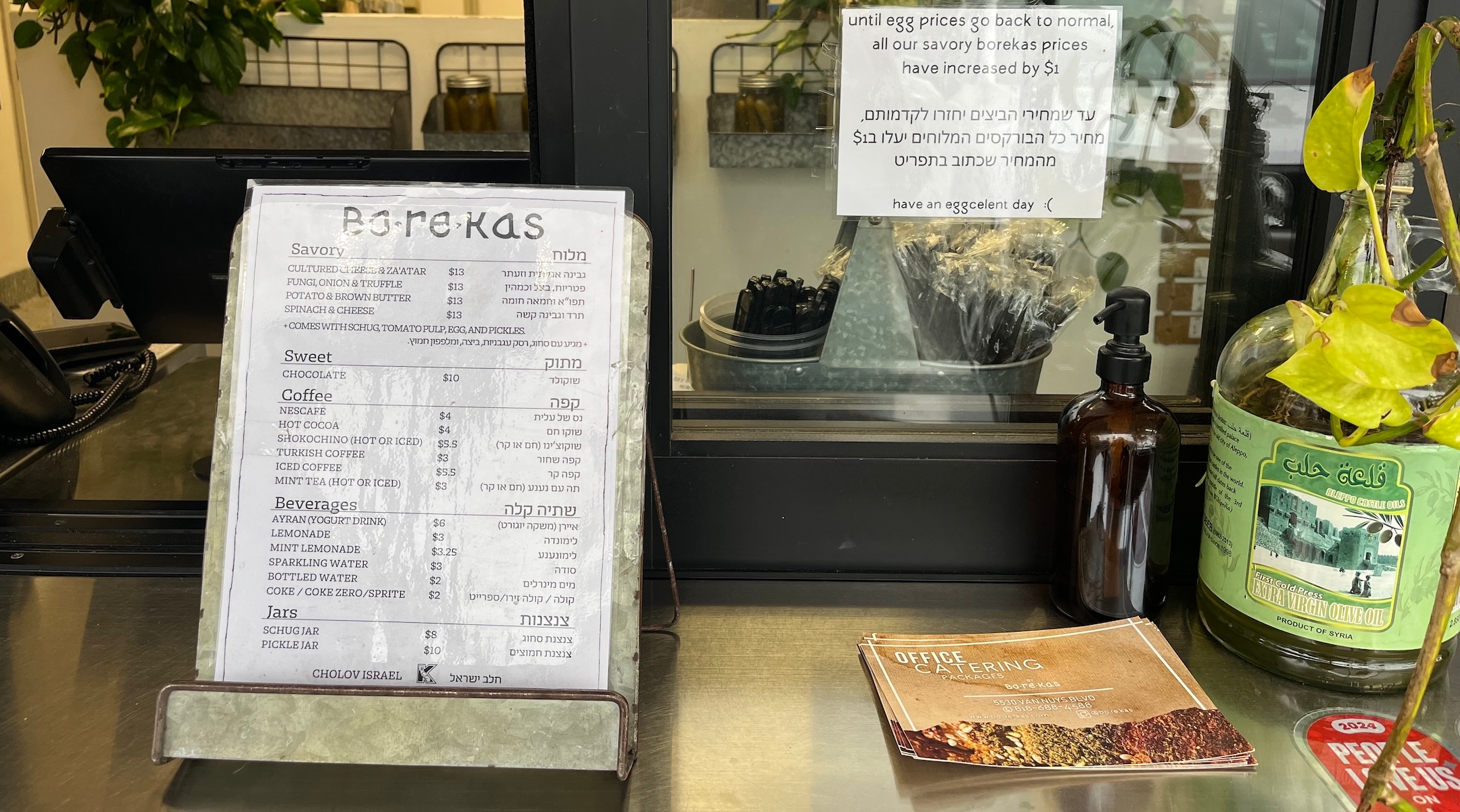

The menu at Bo.Re.Kas Sephardic Pastries in Sherman Oaks, California, is in both English and Hebrew. (Philissa Cramer)

The in-house menu is written in English on one side, Hebrew on the other, and the food, says Gal Waizman, attracts “literally everyone. A Japanese guy comes every Wednesday morning, ordering cafe shachor [a thick, black, Turkish coffee] with cardamom.”

People who didn’t grow up eating it love the bourekas “because it is something different and it tastes good,” she said. “For the Israelis and Jewish people, it is a lot of nostalgia. It hits them and reminds them of home and family. Flavors that they are used to or flavors that they love.”

Another Israeli-Californian packed up his bourekas bags and moved across the country with his wife to open a bourekas shop in Woodbridge, Connecticut, not far from Yale University. Liam Shemi, 22, had long planned to be in the food business and he saw possibilities in devoting his energy to the comfort food he knew from childhood. He opened Crunch at the end of 2024.

“I am Sephardic, Turkish, Jewish. My mother’s family comes from Izmir in Turkey. I grew up eating this food and I learned from my grandma in the kitchen. That was in Israel,” Shemi said. “I grew up with Turkish food and Sephardic culture so when I came here I said, ‘Hey, there is a gap in the market. Nobody knows what it is.’”

He and his wife, Hannah Gimbel, flew to Istanbul to develop their craft, persuading a local bakery to teach them.

“We went in and asked if we could learn how to make it and the guy said come back at 4 o’clock,” said Shemi. “We learned how to make real Turkish bourekas, or Turkish borek.”

Liam Shemi shows off the bourekas at his shop, Crunch, in Woodbridge, Connecticut. (Courtesy Shemi)

Like the Waizmans in Los Angeles, Shemi makes everything from scratch. “We use butter, never margarine, never any artificial things,” said Shemi. And the fillings range from the traditional potato, feta or spinach to what Shemi calls “American flavors,” like cheddar and jalapeno; walnut, kalamata and cheese as well as seasonal flavors like apple jam, made from local apples or, in the fall, a pumpkin filling.

His shop and Bo.Re.Kas are certified kosher; Buba is vegetarian. Shemi, who has grown religiously observant in recent years (and last week was the victim of an alleged antisemitic attack in New Haven), has also added other Israeli-inspired menu items, such as the winter drink sahlep and the pudding dessert malabi.

Shemi sees himself as a trailblazer with big ambitions for bourekas — though he uses the Turkish spelling for the treat. “The same thing happened for pizza 200 years ago when Italians came to America. Nobody knew what a pizza is. Sushi — same thing. Tacos — same thing,” he said.

“Somebody has to pave the path to make the food known and that’s what my goal is,” Shemi added. “I want to introduce it so everyone will know what a borek is and be educated about it. To be able to enjoy it. I don’t want to withhold the world from it.”

If the lines outside Buba even before launch are any indication, the world is ready for what Shemi has to offer.

“Is New York ready for burekas?’” Peleg said by email. “New York is the most open-minded, forward-thinking place on the planet and is always ready for something good.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.