There’s an ignoble tradition of falsified memoirs. “The Hitler Diaries,” a forgery published in 1983, fooled even a Hitler expert. “Misha: A Mémoire of the Holocaust Years,” published in 1997, was sold as a survivor’s testimony but turned out to be a hoax (the part where the author was raised by wolves might have been a yellow flag).

When the truth is revealed, the writers are publicly shamed, and critics and readers debate what is acceptable when shaping the facts for literary or commercial purposes.

But while most readers might agree that a book labeled “nonfiction” should strive to get its facts right, what if the fabrications serve a higher purpose — say, rallying Americans to the anti-Nazi cause?

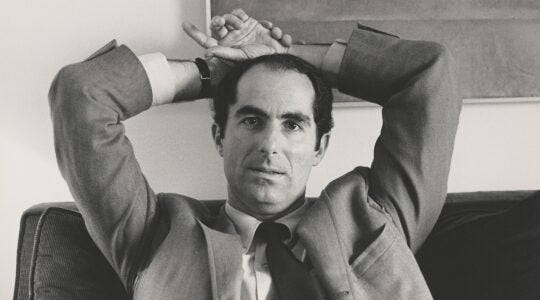

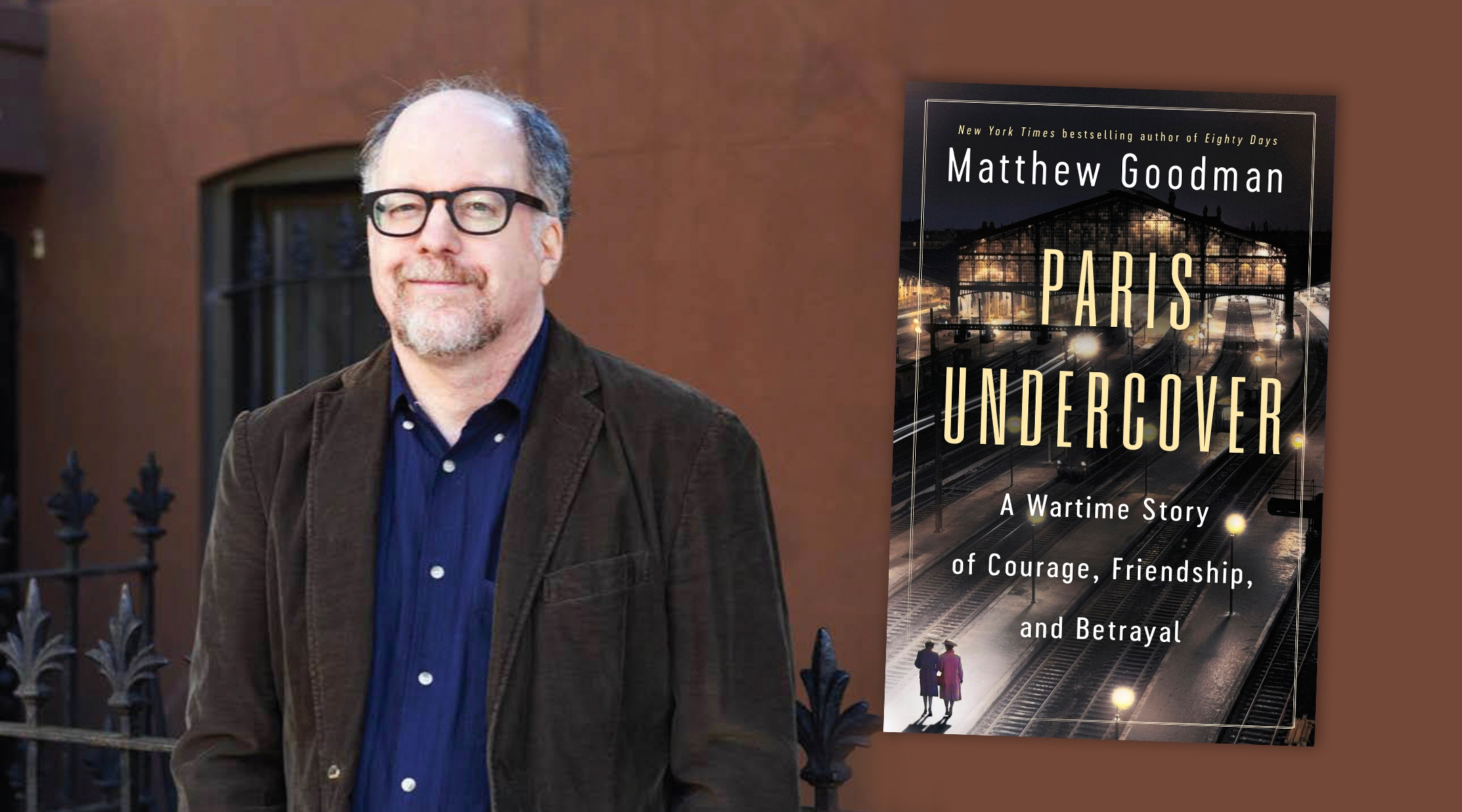

Matthew Goodman didn’t set out to explore that question when he began research for his new book, “Paris Undercover: A Wartime Story of Courage, Friendship, and Betrayal.” He meant to tell the story of Etta Shiber and Kate Bonnefous, middle-aged women in Nazi-occupied Paris who sheltered dozens of British and French soldiers trapped behind enemy lines and smuggled them to safety.

His source text was “Paris-Underground,” an enormously popular account of their exploits first published in 1943 and credited to Shiber and two co-authors. It told how the two women helped establish an “escape line” for soldiers in the first months of the occupation, how both were arrested by the Gestapo, and how Shiber was released after 18 months while Bonnefous (called “Kitty” in the book) continued to suffer in Nazi-run prisons.

The book spent 18 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list on the way to selling half a million copies, with a boost by the influential Book-of-the-Month Club. Constance Bennett, a highly paid star of the 1930s, produced and starred in a Hollywood movie adaptation released in 1945.

“It checked a lot of the boxes that I look for when I write a book: It’s got a dramatic arc. It has interesting characters, it has larger significance,” Goodman recalled in an interview. “My only worry was that I was going to be too dependent on the memoir for my book.”

Not to worry: The more Goodman dug, the more he found much of the book didn’t match the historical record. While Shiber and Bonnefous did run an escape line, the book was largely fictionalized, and Shiber didn’t write it. What’s more, an inspiring story of wartime courage took on a darker tone when Goodman found evidence that the book’s publication actually endangered Kate, at the time still a prisoner of the Nazis.

“Ultimately it becomes a larger, more complicated story and, to me, a more interesting story, because it does get into this sort of moral calculus,” said Goodman. “Kate is obviously betrayed by this publication of the book; Etta is betrayed by the publishers,” who assured her that its publication would not make things worse for her friend. “At the same time, you can understand why they might have said that, because it did help the war effort. It’s a complicated affair.”

Etta Kahn Shiber, a Jewish New Yorker, sailed to Paris after her husband died in 1936. She moved in with Bonnefous, a divorced friend nine years younger. Goodman describes Shiber, while highly cultured, as shy and “terminally anxious”; the British-born Bonnefous was adventurous and independent, owning a business and a sleek car at a time when French women were not allowed to have their own bank accounts.

Matthew Goodman said he began researching the story of the nascent French resistance in 2019, and was “struck by the question of how individuals react in the face of growing authoritarianism, deepening social injustice and a deepening strain of xenophobia.” (Ballantine Books)

When the Nazis marched into Paris in June 1940, the two fled south, but soon returned to Kate’s Paris apartment. Kate, a volunteer with the Red Cross, proposed helping a British officer being held by the Germans in a requisitioned hospital; Etta reluctantly agreed to be her accomplice. After smuggling him out of the hospital in the trunk of their car, the women eventually handed the airman off to an improvised network of shopkeepers, priests, dissident bureaucrats and homemakers who were helping soldiers escape over the border.

“I quote one historian in the book who describes this as the artisanal phase of the escape lines,” said Goodman, adding that the organized French resistance emerged only many months later.

Before the Gestapo came knocking in November 1940, the two women had helped perhaps 40 soldiers — half of them British, the other half French — escape. Many returned to the battlefield, and earned medals for their service.

Etta became the first American woman to be held by the Nazis in France; in her early 60s and already in ill health, she suffered three heart attacks in prison and barely survived. She returned to the United States under a swap in 1942, while Kate, who the Nazis considered a ringleader, languished in solitary confinement.

A book based on their adventures was the idea of a Hungarian Jewish émigré named Aladar Anton Farkas, who had arrived in New York from France in 1941. He read a newspaper account of Etta’s travails and thought the story would make an inspiring novel about the French underground. He took the idea to Paul Winkler, another Hungarian Jew who had fled Paris and reestablished his publishing and literary agency in New York.

Winkler arranged for assistants to interview Etta (Farkas spoke English poorly) over a period of months. With assurances from Winkler and strapped for cash, Shiber agreed to put her name to the book “in collaboration with Anne and Paul Dupre” — the pen names of Winkler and his wife Betty. Farkas went uncredited, and the suit he eventually filed against the publisher, Charles Scribner’s Sons, would provide Goodman with a record of just how much of the book came from the real author’s imagination: Names were changed, characters were invented, and the women were credited with an improbable 250 rescues.

Despite the artifice — and perhaps because of that inflated number — Kate did suffer as a result of the book’s publication. Goodman recounts in detail her torture under the Nazis, and their decision to reinstate her death sentence based on the testimony, however distorted, provided in Shiber’s book. She wouldn’t be freed until the Allied liberation in 1945, and even then she and other prisoners suffered at the hands of drunken Red Army soldiers. She weighed 73 pounds when she arrived back in France.

Lawyers talked her out of filing a lawsuit against Shiber and her publisher, and there’s no indication that two women spoke again after the war. Etta died in 1948; she was 70. Bonnefous died in 1965 at age 79, recognized by the British and French government for her valor but otherwise mostly forgotten.

Goodman — who I knew as the food columnist for the Forward before he began writing deeply researched histories of 19th-century American journalism and the college basketball point-shaving scandal of the 1950s — said his book is about how citizens can fight back when the institutions of government fail them.

A lobby card for “Paris-Underground,” a 1945 film based on the memoir by Etta Shiber. An image of the book appears at lower right. (United Artists)

Goodman said he began researching the story of the nascent French resistance in 2019, and was “struck by the question of how individuals react in the face of growing authoritarianism, deepening social injustice and a deepening strain of xenophobia.

“These two women, who were very unlikely heroines, especially Etta, managed to find resources in themselves and do things that perhaps they did not think they would be able to do,” he added. “They really did risk their own safety and security, even their lives. I think that there’s something quite admirable about that.”

He also notes another way in which Shiber’s purported memoir distorts the record: It doesn’t mention that Shiber was Jewish. Highly assimilated, she was married at the secular Ethical Culture Society by its founder, Rabbi Felix Adler. Her book contains only a few references to the anti-Jewish measures the Nazis were inflicting on France and the rest of Europe.

Goodman thinks the publishers did that intentionally.

“There was such a high level of antisemitism in the United States at that time, and there was definitely a feeling even among the Roosevelt administration that they did not want to too closely equate the Jewish problem” with the war, he said. “There was always this undercurrent fostered by people like [Charles] Lindbergh that American boys were dying to save Jews. Even the Jewish organizations at that time tended to keep a lower profile, because they didn’t want to have the war effort be seen as somehow ‘tainted.’”

And whatever she thought about her own Jewishness or vulnerability, and the risks for Kate, Shiber and her publishers justified the book’s embellishments and omissions in the name of aiding France and liberating Europe.

“It did boost morale. It did,” Goodman said. “It did lead Americans to understand the nobility of the French cause and the resistance.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.