This story contains spoilers for “Apple Cider Vinegar.”

Early in the new Netflix miniseries “Apple Cider Vinegar,” the central character of Millie Blake is diagnosed with a rare cancer and told she must amputate her arm.

Desperate for another solution, Millie seizes on an “alternative” treatment: at a center called the Hirsch Institute, in Mexico. The center is run by the daughter of a German Jewish refugee from the Nazis. Decades after her father’s death, she tells her patients that the medical establishment has tried to suppress her father’s revolutionary therapies.

There, Millie (played by Alycia Debnam-Carey) embarks on a tightly controlled diet of regular juicing and five daily coffee enemas. It initially appears to work, and Millie builds a media empire on her belief that she has cured her cancer without the use of chemotherapy.

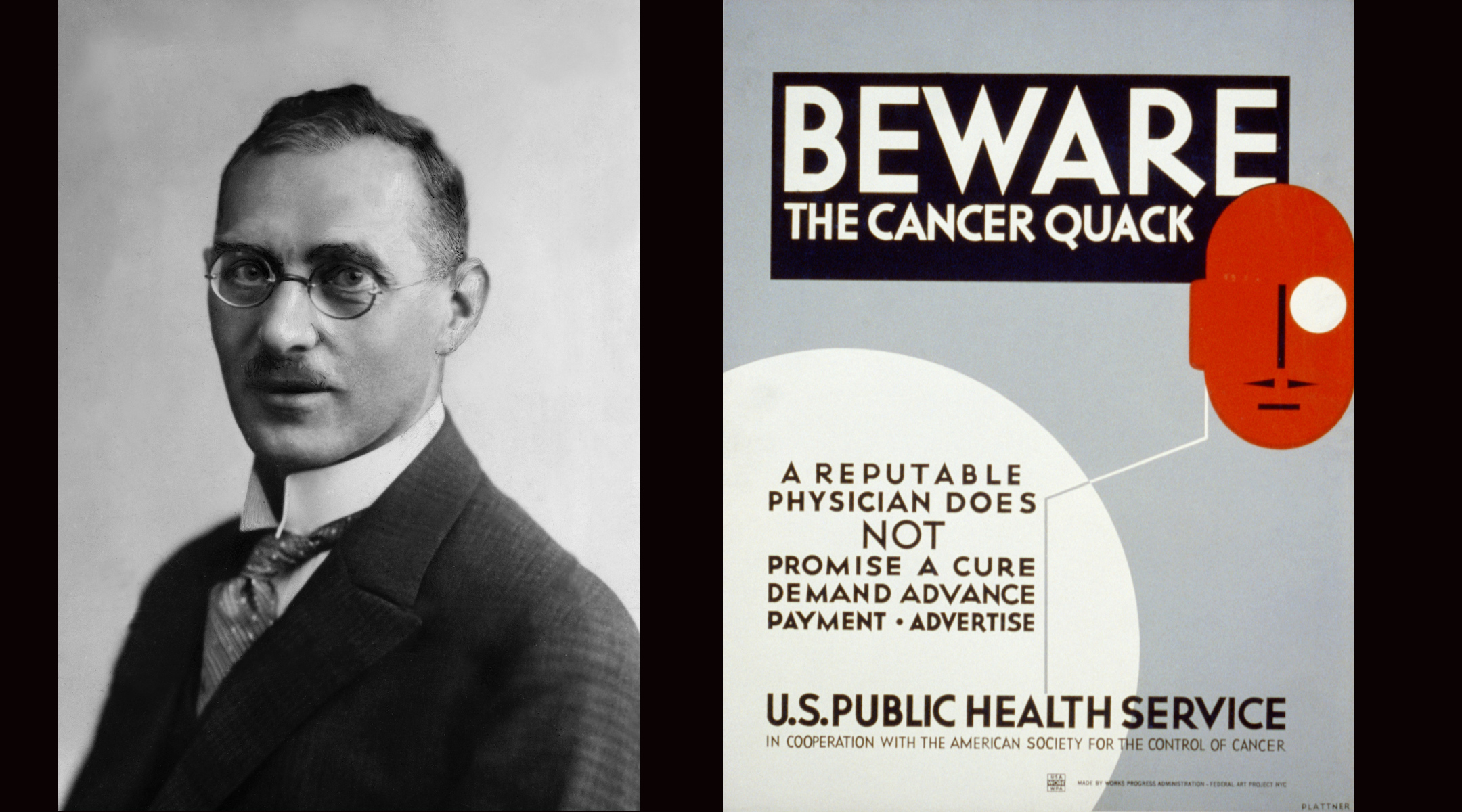

The show is based on the true story of two less-than-honest wellness influencers, and the Hirsch Institute is based on a real place and course of treatment founded by a German Jew. In real life, Max Gerson became a hero to the anti-establishment medicine community, even as his methods have been widely discredited and flagged as dangerous by researchers, who continue to warn cancer patients against him to this day.

Born in Germany in 1881, Gerson received his medical education in Europe, graduating from the University of Freiburg. His interest in seeking diet-based therapies for difficult illnesses surfaced early, as Jewish Telegraphic Agency reports from 1929 describe him as being the “discoverer of a new cure for tuberculosis through rigid diet.” Though Gerson “was derided and mocked at during the experimental period of his cure,” JTA wrote at the time, he “has now gained world-wide recognition.”

Gerson fled Germany for Vienna in 1933 as the Nazis came to power and soon banned all people of “Jewish or related blood” from working for the state — including in the field of cancer research, which Hitler, a hypochondriac, had made a policy priority. Eventually Gerson and his family made their way to the United States.

There, Gerson pursued the newly blossoming field of cancer research with vigor, taking his “rigid diet” protocol even further with unusual treatment methods. He operated a cancer clinic in upstate New York, testified on his methods before the Senate and authored multiple books documenting his methods prior to his death in 1958.

Those methods were unorthodox, to say the least — even for the time. Rejecting the promises of chemotherapy technologies then in their infancy, Gerson instead focused on metabolic therapy, believing that cancer stemmed from a patient’s diet and lifestyle choices and could be excised with a focus on natural foods, juices and expunging toxins from the body.

(L-r) Dr. Max Gerson in 1929; a Works Progress Administration poster warning against “cancer quacks” in 1936-38. (ullstein bild Dtl./public domain)

Gerson came to believe that the medical establishment, which was taking a hardline approach toward rooting out “quacks,” was conspiring to suppress his research. Ironically, the most visible anti-quackery figure during this period was Dr. Morris Fishbein, the Jewish editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, whose zealous lifelong campaign to debunk and discredit pseudoscience led critics to deem him the “medical Mussolini.”

Decades of studies since Gerson’s death have found no evidence that metabolic therapy alone can serve as an effective cancer treatment, and the case studies he chronicled in his book were unconvincing to many researchers.

But that didn’t stop Gerson’s descendants from continuing and promoting his methods, most prominently at the Gerson Institute. Founded in 1978 by Max’s daughter Charlotte, the institute is headquartered in San Diego as a nonprofit but its physical “treatment” center is across the border in Tijuana, where medical regulations are less stringent. It has for decades promoted its “hyper-nutrition and detoxification” regimen to cancer patients around the world.

In the late 2000s it won over a major convert in Jessica Ainscough, whose story heavily inspired the character of Millie in “Apple Cider Vinegar.”

An Australian woman diagnosed with the incredibly rare cancer of epithelioid sarcoma at age 22, Ainscough rejected her oncologist’s advice to amputate the affected arm and instead opted for Gerson therapy. After appearing to find initial success, Ainscough began evangelizing for Gerson and branded herself as “The Wellness Warrior,” becoming a popular influencer.

When Ainscough’s mother was diagnosed with breast cancer, she, too, waved off chemotherapy in favor of the Gerson method, a saga also chronicled with slight variations in the Netflix show. In the series, an elderly woman named Alma Hirsch (played by Robyn Nevin) personally supervises both treatments while deriding chemotherapy as “poison.” She’s modeled after Charlotte Gerson, who in real life continued to claim Gerson therapy could beat cancer and oversaw operations at her family’s institute until her death in 2019 at age 96.

Ainscough’s claim to have beaten cancer with Gerson’s methods was all a mirage — and in due time it collapsed. First, in 2013, her mother died of her breast cancer. Ainscough’s own health then worsened, which at first she tried to hide by wearing long sleeves in public to obscure the effects of the sarcoma (which is also depicted in the show). By the time she could no longer hide the disease’s progression, it was too late for serious medical intervention.

Ainscough died in 2015; Belle Gibson, a parallel wellness influencer who faked cancer and is the show’s central figure, played by Kaitlyn Dever, attended her funeral, as she does in the series.

The Gerson Institute remains active to this day, but now contains disclaimers announcing it “has its limitations, and we can make no guarantees about its effectiveness for every individual; recovery is on a case-by-case basis.”

Particularly in the aftermath of Ainscough’s death, medical professionals have called for the Gerson Institute to be held accountable.

“As outraged as we might have been over Ainscough’s promotion of the Gerson protocol in life, as we mourn, we should also remember that Jess Ainscough was also a victim of the very pseudoscience that she promoted,” Dr. David Gorski, a surgical oncologist at the Karmanos Cancer Institute, wrote on his blog Science-Based Medicine after Ainscough’s death. “Now that she is gone, what I want to know is this: Who are the quacks who enabled her and egged her on? Who are the quacks who conned her into believing that Gerson therapy would save her life?”

Meanwhile, the “wellness” industry — which often includes hostility toward established medical practices — has been shown in some cases to intersect with fascist and antisemitic attitudes while also enjoying cultural reach as never before. This week Robert F. Kennedy Jr., whose anti-vaccine campaigning has led him to make Holocaust comparisons and deem COVID-19 as being “ethnically targeted” to avoid Ashkenazi Jews, was confirmed as President Donald Trump’s new secretary of health and human services.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.