HULA VALLEY, Israel — The trees abutting the road leading to Biriya Forest, a nature preserve in northern Israel, at first resemble spruces turning autumnal shades of red, a sight reminiscent of landscapes in America or Europe but rare in Israel.

A closer look, however, reveals that the trees are only charred remnants — the devastating result of rocket-induced wildfires that destroyed thousands of acres of forest while Israel battled Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Fires break out every year in this forest, which like many others across Israel was planted by the Jewish National Fund, known today as KKL-JNF — but they are usually brought under control quickly. This year, with the local population evacuated and weather conditions unusually extreme, things played out differently.

Starting around May, as temperatures rose, nearly every rocket fired from Lebanon was likely to ignite a fire. And it wasn’t just the rockets themselves: Israeli interceptors exploded overhead, scattering fragments that ignited at multiple points within the forest. The combination of unusual winds, scorching heat and low humidity created a perfect storm that has disrupted entire ecosystems, affected wildlife habitats and undone years of work by foresters aimed at increasing biodiversity.

“We literally witnessed their life’s work go up in smoke,” said Eli Hafuta, director of the Upper Galilee and Golan Region at KKL-JNF, which was founded in 1901 to cultivate Jewish-owned land in the region and today owns 13% of all land in Israel.

“It’s a devastating sight to watch trees that have stood for 70 or 80 years go up in flames,” Hafuta said. “Even younger trees, ones my team and I planted just a decade ago, can be reduced to ashes in just 15 minutes.”

The scorched earth in Biriya Forest reflects just one of many environmental effects of nearly a year and a half of war for Israel. Less visible than the lives lost, injuries sustained and homes destroyed has been devastation to flora and fauna in both Israel’s north and south.

The cascading effects continued this week as the splashy kickoff for a new forest in the western Negev to honor war victims, timed to the Jewish environmental holiday of Tu Bishvat on Thursday, was canceled amid rising security threats in the region. A handful of Israeli officials are instead holding a smaller planting ceremony in the western Negev, at a site named for an officer killed on Oct. 7, 2023.

Cranes seen at the Hula Valley lake, northern Israel, Jan. 23, 2025. (Ayal Margolin/Flash90)

Perhaps nowhere has the war’s effect on Israeli ecosystems been more pronounced than at the Agamon Hula Valley Nature Reserve, famed for its mesmerizing bird migrations.

Twice a year, hundreds of millions of birds — including cranes, pelicans, and storks — pass through the valley, in a normal year turning it into a hotspot for ecotourism, with the BBC naming it one of the top 10 birdwatching sites in the world.

During the months it was closed — from Oct. 7, 2023, until well after the ceasefire on Israel’s northern border took hold in late November — the Agamon Wildlife Rehabilitation Center on the reserve turned into what staff call the world’s first wartime field hospital for animals.

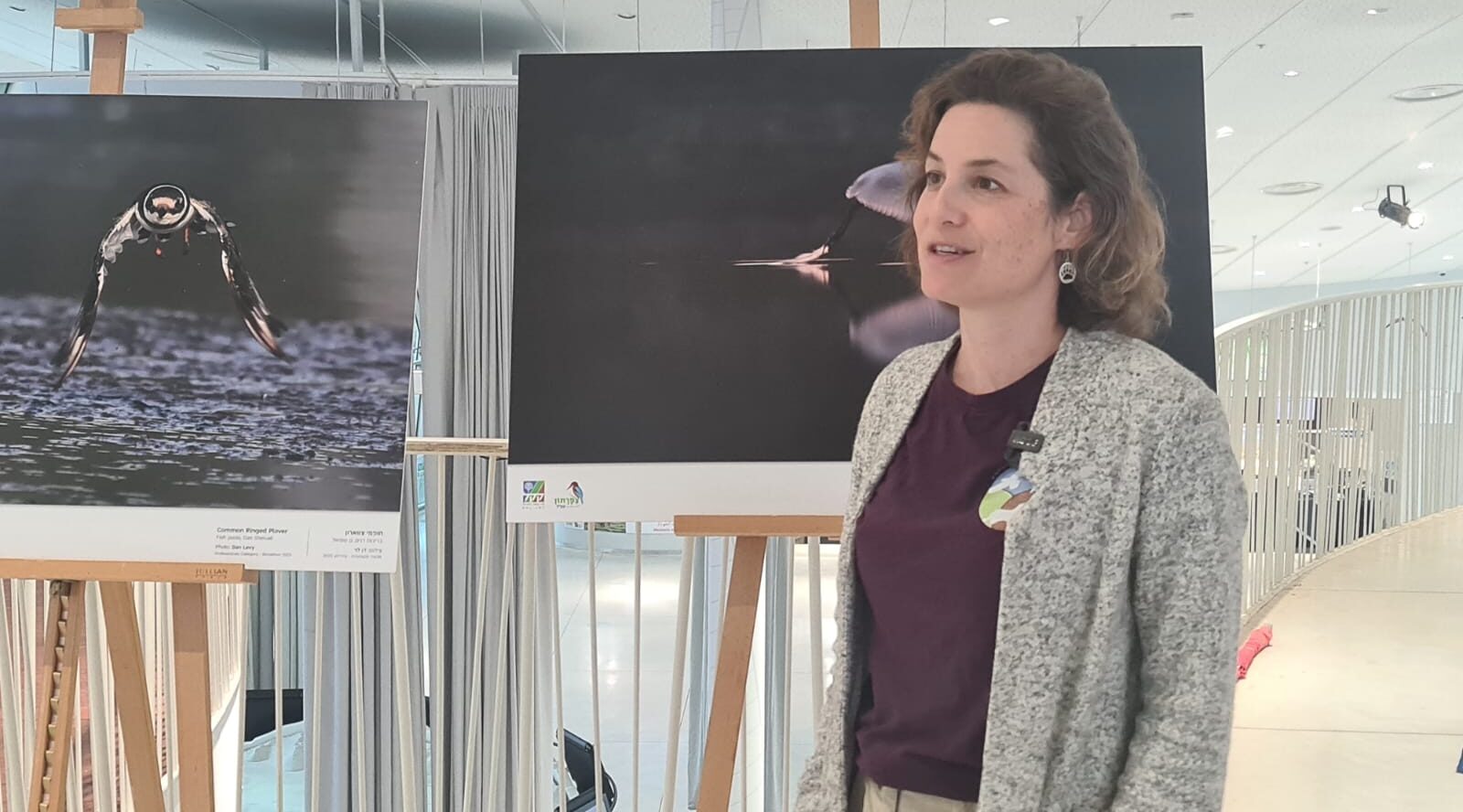

“We’re the first rehabilitation center in the world with a war protocol,” said Dr. Rona Nadler-Valency, the center’s head veterinarian and director.

When rockets pounded the north, Nadler-Valency and her team were evacuated from their communities, forcing the center to operate remotely, with staff caring for injured animals at home when possible. After three months, the team began returning, resuming treatment at the center under a chaotic new normal.

Dr. Rona Nadler-Valency, director of the Agamon Hula Valley Nature Reserve, had to stop animal surgeries because of rocket fire throughout 2024. (Deborah Danan)

“We would be in the middle of surgery, an animal on the operating table, when the sirens would go off,” Nadler-Valency said. “We’d have to leave everything and run to the shelter — sometimes dozens of times a day.”

At other times, Nadler-Valency and her team were caught outdoors when sirens sounded, forcing them to drop to the ground for cover. “Those moments felt like pure insanity, but at least we were able to keep doing our work,” she said.

With so few civilians remaining in the north, many of the wounded animals were brought to the center by soldiers.

In one case, Lilit, a tawny owl brought in after being hit by a military vehicle, suffered a severe head injury that temporarily left her blind and deaf. Lilit was carefully monitored and rehabilitated in a specialized acclimation cage. Treatment was complicated by the ongoing missile fire, requiring the team to carefully time their visits to her, but eventually the team managed to restore her sight, hearing and flight. After a month and a half in the cage, Lilit was released back into the wild with a transmitter on her back, allowing the team to track her recovery and ensure she could hunt and survive, as well as gain insights into how owls adjust to life after similar injuries.

“Cases like Lilit’s,” Nadler-Valency reflected, “were rays of light amid the madness.”

The disruption fueled other changes that scientists are now tracking. Yaron Charka, chief ornithologist at KKL-JNF — which manages the reserve and its reopened visitors’ center — observed an increase in wintering bird species this year.

The damage caused to the Biriya Forest in northern Israeli city of Tzfat, following missile attacks from Lebanon, July 10, 2024. (Avshalom Sassoni/Flash90)

“I’m seeing a great variety of birds this winter, compared with last winter, where there were few,” he said, but acknowledged that he didn’t fully understand why.

Every winter, some 50,000 common cranes settle in the Hula Valley, pausing their southward migration to Africa. But last year, that number dropped by 70% amid constant rocket fire from Lebanon, just 30 kilometers from the valley.

Still, Charka cautioned against attributing all of the changes to the cross-border clashes.

“During wartime, birds can change their route and bypass us in isolated instances — we saw this with Ukraine — but it’s not the whole picture,” he said, noting that the ceasefire came at the end of the migratory season and emphasizing that climate change, which is having an outsized effect on Israel, is also causing changes in the cranes’ migration habits.

“In the past two years, the arrival of the crane flocks in the fall to the Hula Valley has been significantly delayed,” he said. “It is important that we continue to monitor this trend.”

The site’s extended closure left the cranes unaccustomed to humans, so camouflaged wagons now help visitors observe them closely while minimizing disturbance.

With the return of crane populations comes the resurgence of old problems, particularly the challenge of protecting local crops from the birds. Farmers have long used methods such as gas cannons and mirrors to divert the cranes to designated feeding sites, but these approaches are costly and disruptive — both to wildlife and to tourists.

Yaron Charka, KKL-JNF’s chief ornithologist, stands outside the Agamon Hula Valley Nature Reserve in northern Israel, January 2025. (Deborah Danan)

Now, KKL-JNF Jewish National Fund is developing a laser-based system to address the issue more sustainably. The technology, developed in conjunction with an Israeli ecotech company, employs cameras, lasers and artificial intelligence to detect crane presence and direct a laser beam that the birds perceive as chasing them, causing them to relocate. Charka, who used to work in tech, said he hoped to see the system fully operational by the next migration season.

According to the reserve’s director, Inbar Shlomit Rubin, far fewer bird nests were observed in the spring — a trend for which she saw two immediate explanations.

“The unrest and insecurity led many birds to migrate further south to quieter areas of Israel,” she said. But mammals and smaller animals had no means of escaping the area.

“The noise of the war caused immense stress,” Rubin said. “Stress negatively affects fertility.”

A rainbow can be seen over Biriya Forest in 2024. (Courtesy Eli Hafuta)

Since the ceasefire, KKL-JNF has launched an extensive survey of the areas burned over the past year to evaluate their potential for natural regeneration. For now, most of the organization’s efforts are focused on urgent interventions in visitor-accessible areas.

While the restoration of the affected areas is expected to be a long-term endeavor, Hafuta expressed optimism, highlighting forests’ remarkable ability to regenerate. He said he estimated that as many as 70% of burned trees would begin to regenerate naturally in the next year and a half.

According to Rubin, in recent weeks, wildlife, too, has begun returning to the affected areas.

“We’ve noticed a very subtle, minimal return. While the long-term effects are still uncertain, we remain hopeful that [the war] won’t have a significant impact in the years to come,” Rubin said. “The trauma the area experienced will take time to heal, but we are on the right path.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.