Over the years I have received notes and cards from my partner with lines from ancient Bedouin love poetry. I always enjoy the soulful stanzas, the emotions conveyed and the rhythmic quality of the poems, but I never really thought much about how these poems, composed in a culture that is primarily oral, came to be preserved and accessible enough to be penned inside anniversary cards.

It was only years later that I was introduced to the scholar responsible for their preservation, Clinton Bailey. It is thanks to his curiosity, wanderlust, outgoing nature, love of all people and individual foresight that the oral poetry, laws, narratives, rituals and proverbs of the nomadic tribes of Bedouins from the Israeli Negev, Jordan and Sinai Peninsula were preserved for posterity and shared with the world at large. He is often credited with creating the academic field of Bedouin studies in Israel.

On Jan. 5, Bailey, known to his close friends as “Itzik,” died in his home in Jerusalem. He was 88.

For more than 50 years, Bailey immersed himself in Bedouin communities, living for weeks on end in the harsh conditions of the desert, traveling by camel — with his journal and tape-recorder in hand — conducting interviews in the Bedouin dialect of Arabic and befriending elder tribesmen, women and children alike, preserving a culture that was disappearing. With technology starting to seep into the communities and a move towards more urbanization, the traditional culture of the Bedouin was changing beyond recognition.

Bailey’s life work, described by one Bedouin colleague as “sacred,” has preserved Bedouin culture not just for the world of scholars, poets and readers but for the next generation of Bedouin children. While documenting and traveling in and out of communities, he became a cherished friend of and fierce advocate for Bedouins at large.

Bailey was born Irwin Glaser in Buffalo, New York, in 1936 to an upper-middle-class secular Jewish family that owned a chain of gas stations. As a child he lived just below the family of Seymour (Sy) Gitin, who became an archaeologist and director of the Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in East Jerusalem. The two would cross paths again, with their children attending the same nursery in Israel. Glaser changed his name to Clinton Bailey — taking the name of the intersection where his father’s first gas station stood — ostensibly to ease his research travels to the Middle East.

Bailey’s interest in Bedouin culture stemmed from a series of coincidences. While spending a summer studying art in Oslo, he came upon a copy of the Partisan Review which contained the story “Gimpel the Fool” by Yiddish author Isaac Bashevis Singer, translated by Saul Bellow. It was the first essay of Singer’s to be translated from Yiddish into English and published in a literary journal. Bailey’s curiosity was piqued to discover that “this, too, was Judaism.”

Later, while posted in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Bailey looked up Singer in the phonebook and gave him a call, asking if the two could meet. The future Nobel laureate was so taken by this Jewish kid in a Navy hat that they wound up meeting repeatedly. Eventually the desire to learn Yiddish led Bailey to a program for studying Hebrew.

His Hebrew teacher was a kibbutznik who opened his eyes to the new country of Israel, then just 10 years old. Bailey moved to Israel in 1958. After completing his BA at the Hebrew University and then his PhD in Middle Eastern studies at Columbia, he returned to Tel Aviv to look for work. Years later, in another chance encounter, this time on the streets of Tel Aviv, he met Paula Ben-Gurion, the wife of Israel’s founding prime minister. Paula told him that her husband was looking for English teachers to work in his southern Negev kibbutz, Sde Boker.

During afternoons in Sde Boker, Bailey would often chat with the retired politician, as they walked about the kibbutz. “He wasn’t into small talk,” he recalled in a 2017 interview with the New York Jewish Week. “If I asked a question, he’d answer.”

Fifty years later, recordings of those conversations became the basis of “Epilogue,” an acclaimed 2016 documentary.

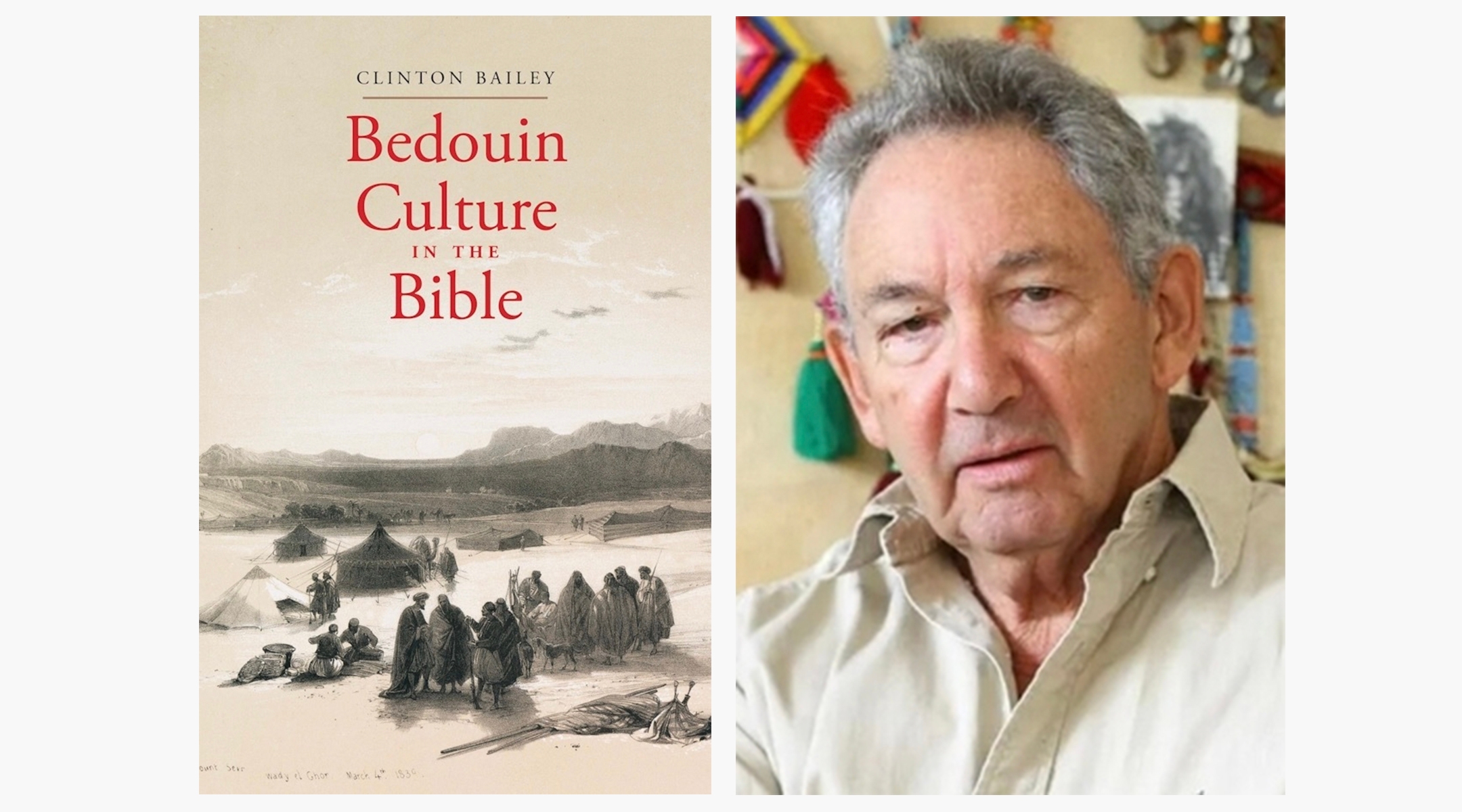

Clinton Bailey published the book “Bedouin Culture in the Bible” with Yale University Press in 2018. (Yale University Press; Michal Fattal/Wikipedia)

Bailey took a job teaching English on the kibbutz and at the same time became an observer of the local Bedouin in the Negev. While jogging and exploring he would often meet Bedouin shepherds and start conversations with them. Bedouins, known for their value of hospitality, would often invite him back to their tents. On his visits he was able to weave together their narratives.

Fascinated by their lives, habits and ways of being, he began interviewing community members about their traditions and laws, which ultimately led to five decades of immersive and intimate research, collecting narrative data and recording oral traditions. He wrote scores of articles and four books, including “Bedouin Poetry from Sinai and the Negev” and “Bedouin Culture in the Bible.”

In 2021 he donated his archive of 350 hours of audio tape, photographs and slides to the National Library of Israel. The library described the archive as “a treasure of orally transmitted ancient culture, now irreplaceable, and not available via the younger generations of Bedouin who grew up exposed to modernity.”

While on a shiva visit to the Bailey home in Jerusalem, I noticed, among artifacts, photographs, maps, wall tapestries and desert musical instruments collected on his journeys, a letter from Israeli President Isaac Herzog praising Clinton for his life and work, his contributions to both Bedouin and Israeli societies, and to humanity at large.

The shiva house was full of life, with visitors who included the mayor of the Arab Bedouin city Rahat; American and Israeli family and friends; esteemed scholars from around the world; writers; neighbors; children and grandchildren, all looking at photographs and recounting stories of Bailey’s life, his adventures and his love of people. Reflecting the spirit of hospitality that he received in so many Bedouin tents, the dining room table was filled with an array of delectable treats, drinks, pastries and fruits from across the region, bridging worlds and bringing people together in a way that was uniquely his own.

Until the very end of his rich life, Bailey was brainstorming what his next project would be. Just this past summer over coffee at a Jerusalem cafe with my partner Aaron, as well as at a lively dinner party he hosted in his home, Bailey outlined the sketch of a book project and invited Aaron, a Near Eastern studies scholar, to collaborate with him. He was fascinated by the idea that the Bedouin lifestyle could reveal how ancient Israel lived and thus illuminate the Hebrew Bible, which he loved. I am saddened that the collaboration will never come to be but I hope that the project will nonetheless be carried forward, enabling Clinton Bailey’s scholarship, legacy and deep love for humanity to continue enriching us.

He is survived by his wife Maya; his four sons Michael, Daniel, Binyamin and Ariel; their spouses and nine grandchildren.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.