In a fraught moment in the film “A Real Pain,” Kieran Culkin, playing the more volatile of a pair of Jewish cousins who go on a roots tour of Poland, berates his fellow travellers for riding in a first-class train car in a country where so many Jews rode cattle cars to their deaths.

A few scenes later, after breaking away from the tour group, he happily sits in first class, essentially telling his cousin, played by Jesse Eisenberg, “Screw it. We’re owed this.”

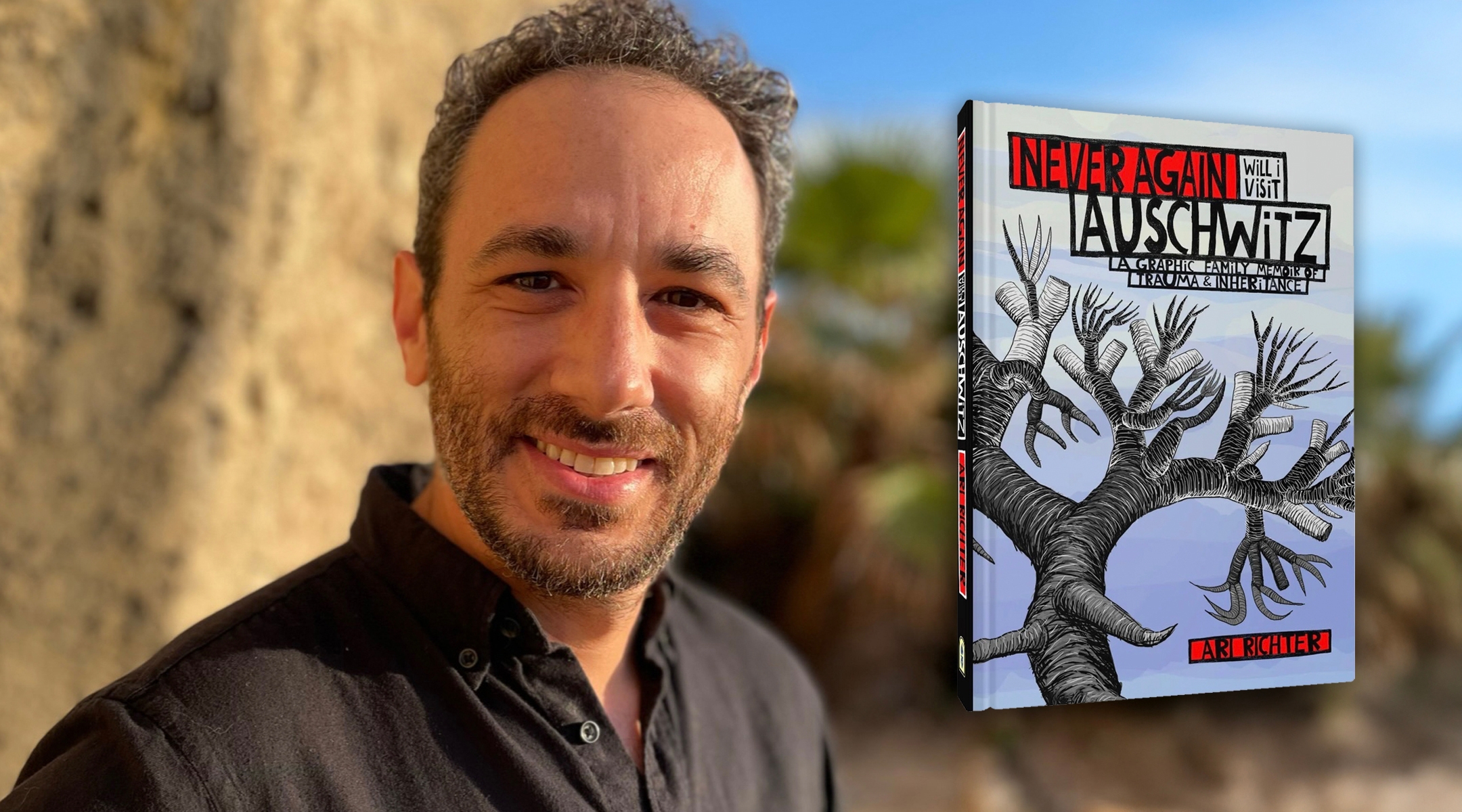

“I love that scene,” said Ari Richter, the author and illustrator of “Never Again Will I Visit Auschwitz,” a “graphic family memoir” describing Richter’s own visits to the places where his Holocaust survivor grandparents lived and suffered. Richter said that in the train scenes, “A Real Pain” expertly captures the contradictions felt by second and third generation Jewish visitors like him on pilgrimages to a grim Jewish past.

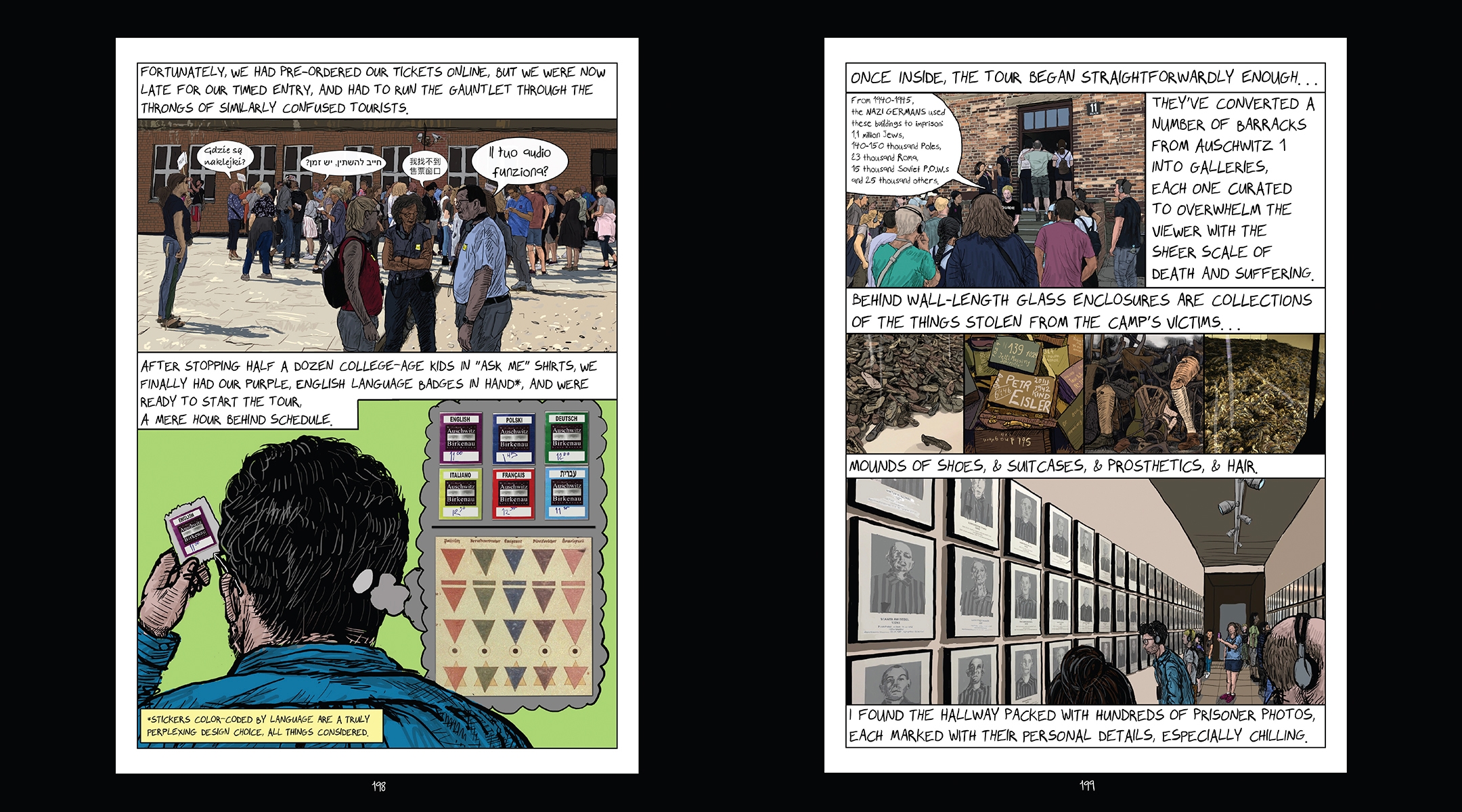

In his book, Richter describes those emotions on a visit to the Dachau camp memorial. He is both impressed by the efforts made by the German curators to focus on “the nexus of German cruelty and Jewish suffering” (unlike the Polish guides at Auschwitz, where he learns “mostly about the suffering of non-Jewish Poles”) and touched by small gestures, like the “kosher-friendly options” on the menu at the Dachau café.

And yet …

“In a way, I know they seek my absolution,” Richter ruminates back at the hotel, “and I resent that I offer it by accepting their kindness.”

Richter’s is a multilayered book, published last summer, about his grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ imprisonment in Dachau, Buchenwald and Auschwitz; the lives they made in America (including Tampa, Florida, where Richter grew up); and what Richter calls the safe, “white American identity” he inherited. Richter draws on the survivor memoirs written and recorded by his relatives, collaging actual photographs with his own scratchy but realistic drawings.

“There’s a certain point where I realized that my parents weren’t going to be the ones telling their parents’ story, so it sort of fell into my lap generationally,” Ari Richter said of his graphic memoir. (Fantagraphics Books, Inc.)

But two important episodes in the book feature his roots-slash-research trips – in 2019 and 2021 — that included stops at Auschwitz, Dachau, Jewish cemeteries and his grandparents’ hometowns in present-day Poland and Germany.

The book describes a process familiar to Jewish visitors to the death camps and the former homes of vanished loved ones: an occasion to face the enormity of the Holocaust, the inheritance of family trauma and what being Jewish means to the pilgrim. In “Never Again…,” between scenes depicting his grandparents’ stories, Richter asks in the present if his relatives’ survival and second chances give him license to put the past aside, and what lessons about Jewish life and survival he’d like to pass on to his children.

Richter’s book arrives at a perhaps not coincidental moment that recently saw the release of two films about such roots trips — “A Real Pain” and Lena Dunham’s 2024 film “Treasure.” They join a genre that already includes Jonathan Safran Foer’s 2002 novel “Everything Is Illuminated,” Francine Prose’s 1997 novella “Guided Tours of Hell” and screenwriter Jerry Stahl’s 2022 memoir, “Nein, Nein, Nein!”

So-called “dark tourism” has even spawned its own academic sub-specialty: In her 2014 book “Jewish Poland Revisited: Heritage Tourism in Unquiet Places,” anthropologist Erica T. Lehrer describes encounters between Jewish tourists and Polish locals and their halting and occasionally hostile attempts to understand each other. In “Dark Tourism, the Holocaust, and Well-being,” three academics offer an almost comically understated review of the literature: “Dark tourism carried out by Jewish people often has a transformative effect, despite the negative emotional impact it can have on these dark tourists.”

Comedy is not the first thing that comes to mind when you consider visits to death camps, but if there is one thing the popular treatments of the visits share, it is a mordant sense of humor. Foer’s novel, and its 2005 film adaptation, is about the Jewish author’s journey to Ukraine in search of the woman who saved his grandfather’s life during the Nazi liquidation of the family shtetl. Perhaps the best known character in the book is a local handler who speaks a comically broken English.

Jesse Eisenberg and Kieran Culkin play cousins who visit Majdanek while on a heritage tour of Poland in “A Real Pain.” (Courtesy Searchlight Pictures)

Prose’s novella is about an obscure playwright enduring a tour of a concentration camp led by a flamboyant and much more successful writer who himself survived the camp. The tone, like the title, is satiric and pitch black.

And in “Treasure,” playing a journalist who accompanies her survivor father on a trip through 1990s Poland, Dunham goes for bittersweet comedy before the inevitable visit to Auschwitz and her father’s stolen home.

The humor could be a distinctly Jewish response to tragedy, or a choice to make morbid material more palatable to a wide audience. The very idea of death camps being turned into tourist sites, with gift shops and snack bars, is the sort of “ludicrous” incongruity that everyone from Freud to Schopenhauer to Mel Brooks include in their theories of laughter. Eisenberg told interviewers that “A Real Pain” was inspired by an advertisement promising a “Holocaust tour, with lunch.”

Stahl’s gonzo travelogue gleefully mocks the tourist trappings at Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Dachau, but he ultimately concludes that they don’t diminish the impact of his visits. “I don’t care if you can buy a slice after the crematorium and wash it down with Fanta,” he writes. “Nothing, in the end, can diminish the searing gravitas of the physical place on which the martyrs, our ancestors, walked.”

Holocaust tourism has also spawned unrelentingly somber books. In his 2014 novel “In Paradise,” the late writer Peter Matthiessen describes a real-life “Bearing Witness” meditation retreat held at Auschwitz-Birkenau. The tone is as chilly as a Polish winter. And in “The Memory Monster,” a slim, searing 2020 novel by the Israeli writer Yishai Sarid, an Israeli academic who conducts tours of the camps for school groups and tourists has a breakdown under the weight of the memories he is forced to carry and convey.

What “A Real Pain,” “Treasure” and Richter’s graphic memoir also share is the age of their creators: Richter and Eisenberg are both 41 and Dunham is 39. On Monday, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the world will mark 80 years since the liberation of Auschwitz, meaning living Holocaust survivors could only have been youngsters when the war ended. Their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren learn about the Holocaust second-hand in an inheritance that some call “generational trauma” and Richter calls a “generational trust.”

A spread from “Never Again Will I Visit Auschwitz” depicts the author’s guided tour of the camp complex. (Fantagraphics Books, Inc.)

“There’s a certain point where I realized that my parents weren’t going to be the ones telling their parents’ story, so it sort of fell into my lap generationally,” said Richter, a professor of fine arts at The City University of New York (and one of the New York Jewish Week’s “36 to Watch” in 2024).

These third-generation works also share an intense self-consciousness: Eisenberg and Dunham focus less on the history of the Holocaust or the experiences of the victims and survivors than on the interiors of the young protagonists.

“A Real Pain,” with its tight focus on two millennial Jews facing the loss of their grandmother, has been criticized for being more of a buddy dramedy than a real confrontation with the horrors of the Holocaust. But the film’s scenes set in the Majdanek concentration camp are somber and emotionally draining, as is a montage juxtaposing current sites in Lublin with descriptions of the yeshivas, synagogues and Jewish homes that they replaced.

And others see the film’s focus on the characters’ individualized pain and personal grieving as its strength: New York Times critic Manohla Dargis writes that the dark history the cousins confront is “inseparable from the existential reality of their grandmother, from the woman and the mother she became, and from the family that she had.”

Richter’s book, by contrast, digs deep into his relatives’ histories and memories — throwing his own struggle to make sense of the “generational trust” into sharp relief. In the book his sense of complacency as a middle-class Jewish American is shattered by the massacre at the Tree of Life synagogue in 2018 and the resurgence of the far right. He finds solace in the words of his grandfather Karl: “I am ultimately an optimist — I have to be. Because the haters have won if they succeed in hardening your heart.”

Late in his book, after the birth of a daughter, Richter begins to consider the next generation. “I want her to feel completely free in the world,” he writes, “unencumbered by the pressures of Jewish continuity and undoing Hitler’s work.” At the same time, he finds it sad to think about a cultural heritage “erased through assimilation into generic American whiteness.”

“I want them to be well aware of their history. I made this book for them,” he told me, in what could be a mission statement for Holocaust tourism. “It’s a starting point for them to do their own research, go down their own rabbit holes and to learn more about that history. It’s a starting place for them to explore their family history and their Jewish history.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.