Nearly every day someone or other on my social media feeds will share the same quote by Hannah Arendt. It reads:

This constant lying is not aimed at making the people believe a lie, but at ensuring that no one believes anything anymore. A people that can no longer distinguish between truth and lies cannot distinguish between right and wrong. And such a people, deprived of the power to think and judge, is, without knowing and willing it, completely subjected to the rule of lies. With such a people, you can do whatever you want.

It’s a damning quote about autocracies by the late German-Jewish political theorist, whose book “The Origins of Totalitarianism” has also found a new audience in a political climate where lies and misinformation are flowing down from high office, where Democrats and Republicans can’t agree on a common set of facts, and where Mark Zuckerberg said his company will no longer moderate hate speech and misinformation on Facebook and its other platforms.

The only problem? Arendt never said it — or at least not exactly. As the Arendt scholar Roger Berkowitz pointed out over the summer, Arendt said and wrote “many similar things,” but the viral quote seems to have been patched together from various other statements she made in a long and prolific career.

Berkowitz isn’t the only one to note the irony that a philosopher who considered truth “the ground on which we stand and the sky that stretches above us” is represented by someone else’s version of what she did or didn’t say. But distortion may be the inevitable consequence of celebrity: Interest in Arendt, who died in 1975 at the age of 69, is riding a wave that hasn’t crested.

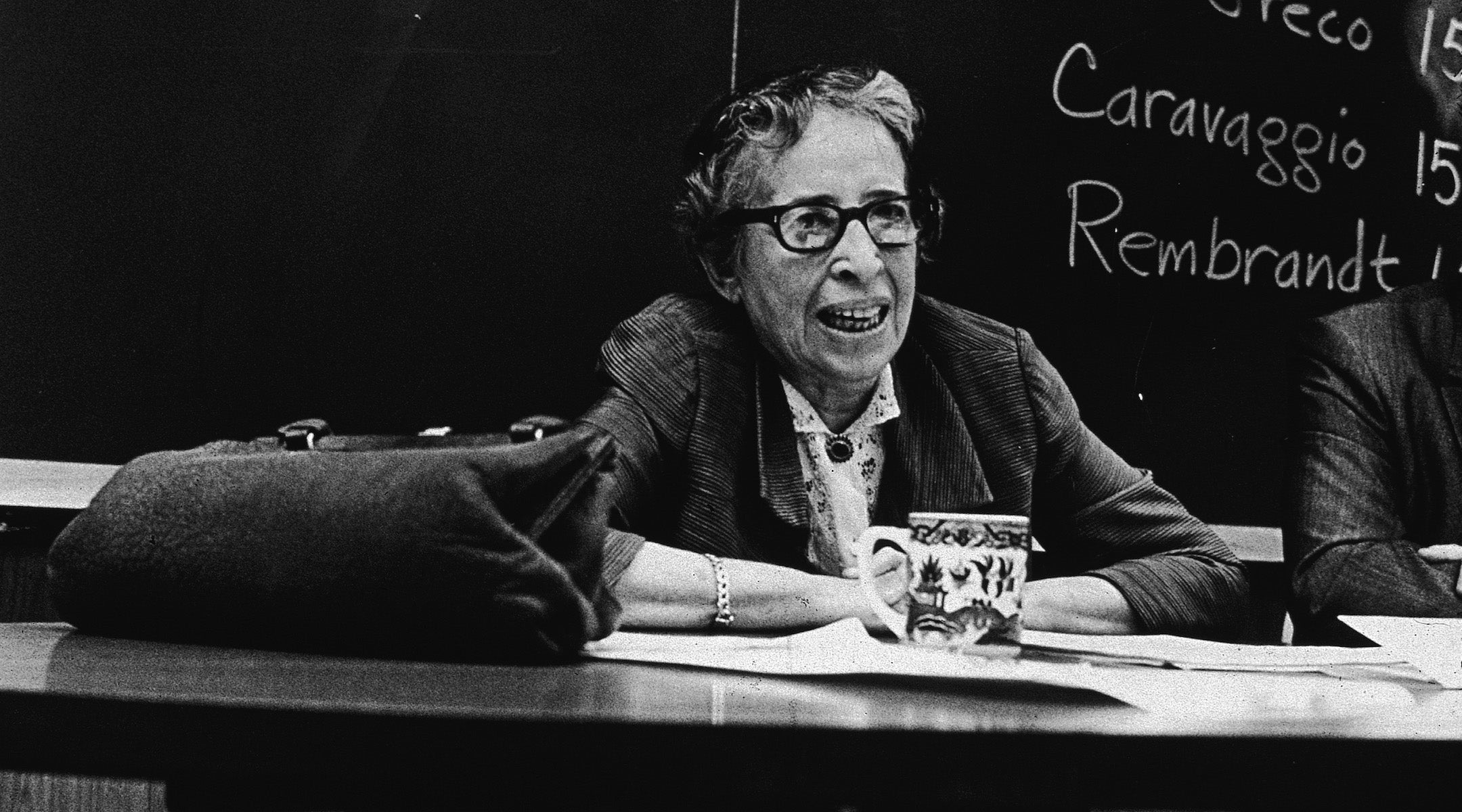

Hannah Arendt conducts a seminar at The New School in Manhattan, Feb. 19, 1969. (Neal Boenzi/New York Times Co./Getty Images)

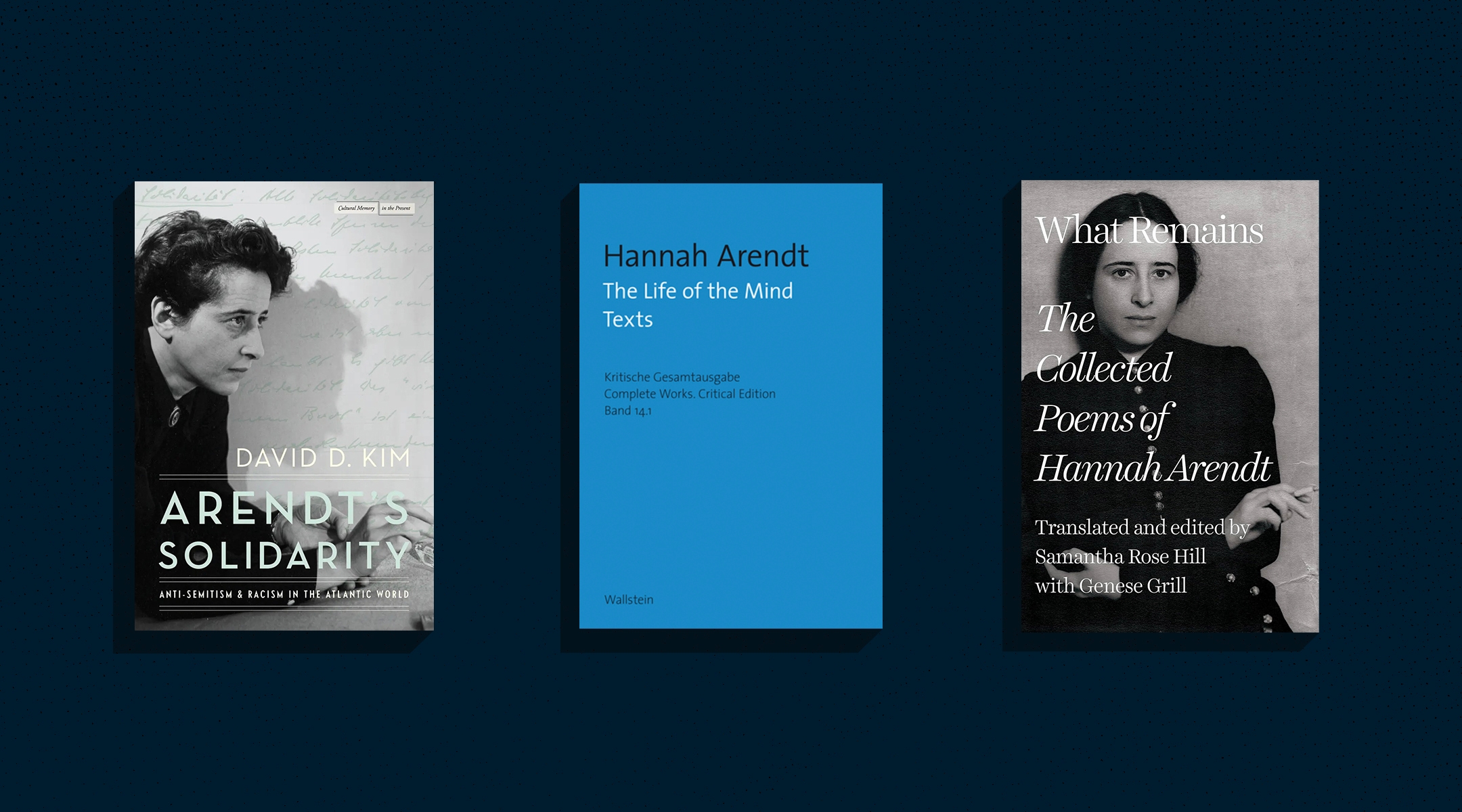

A new book, “What Remains: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt,” gathers and translates all of Arendt’s poems for the first time in English. A new, critical edition of her unfinished final book, “The Life of the Mind,” came out last year to glowing reviews. A recent study by UCLA scholar David Kim, “Arendt’s Solidarity: Anti-Semitism and Racism in the Atlantic World,” explores her notions of intergroup cooperation in the fight against bigotry — and her blind spots in applying the notion of solidarity to African-Americans and other oppressed groups.

The Israeli media have discovered — or re-re-discovered — her thoughts on war and responsibility in the 15 months since Oct. 7. Vera Weidenbach, in Haaretz, invoked Arendt in criticizing the failure of the progressive left to condemn Hamas, in calling Benjamin Netanyahu a “wannabe dictator,” and in decrying “the deterioration of moral standards” among the Israeli public.

Another Haaretz columnist, Robert Zaretsky, wrote that Arendt would have found Israel’s initial response to the Hamas massacre “utterly justifiable” — and would also have supported the International Criminal Court’s decision to prosecute Hamas and Israel for war crimes.

Conservative pundit Bret Stephens embraces her anti-totalitarian writings; a contributor to Sapir, the journal he edits, quotes her in rebuking “post-colonialists” who justified the Oct. 7 attacks.

Of course, Arendt isn’t around to defend or deny these appropriations. And because she wrote so much and in language that was painstakingly nuanced, she’s ripe for cherry-picking. Her ideas are invoked in conversations about a host of contemporary ills: authoritarianism, racial- and gender-based violence, climate change, and right-wing populism, to name a few.

“People like to appeal to her because her name brings a sense of authority and weight into a conversation. You know, some people joke about ‘St. Hannah.’ She can’t do anything wrong,” said Samantha Rose Hill, author of a 2021 biography of Arendt and editor of the new collection of her poems. “She was very anti-ideological. And so there’s a question for readers about how seriously they take her position on certain topics, and to what extent she’s just trying to get us to think about the different sides of the political argument.”

Arendt was born in 1906 in what is now Hanover, Germany, to secular, middle-class Jewish parents. Having read all of Kant’s works by the age of 14, she received her doctorate in philosophy at the University of Heidelberg when she was 22.

In 1933, she spent eight days as a prisoner of the Gestapo, jailed for the research into antisemitism she had done for the World Zionist Organization. Released, she fled to France, where she worked for Youth Aliyah, helping Jews immigrate to Palestine. She was eventually able to escape through Spain and Lisbon to New York, where she arrived as a stateless refugee in 1941.

At Columbia University, the eminent Jewish historian Salo Baron helped Arendt get published in English and land a teaching post in modern Jewish history at Brooklyn College (she later taught at Princeton, The New School and the University of Chicago). Baron also hired Arendt as head of Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, an organization charged with rescuing heirless Jewish books and artifacts stolen by the Nazis.

“The Origins of Totalitarianism,” published in 1951, established her reputation and her place as one of the “New York Intellectuals,” a largely Jewish tribe of left-leaning, anti-Stalinist writers.

Their political disputes were fierce and legendary, and many in the crowd turned to the right with the rise of the radical left and its disdain for Israel. Arendt, fiercely independent, was hard to pin down ideologically, but she drew across-the-board ire in 1963 when her coverage of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a mastermind of the Holocaust, appeared in The New Yorker. Critics charged that the now famous phrase she used to describe the Nazis’ genocidal enterprise, “the banality of evil,” minimized Eichmann’s crimes. Worse, they said, she had shown remarkably little empathy for the Jews forced into collaborating with their tormentors.

Arendt’s reputation took another, posthumous, hit in 1982 when a biographer wrote about her youthful love affair and lasting friendship with the famed German philosopher and later Nazi Party member Martin Heidegger.

Her defenders, however, remained fiercely loyal to her work and her legacy. They included Jerome Kohn, who died in November at the age of 93. Much that was written and said about her was “preposterous,” wrote Kohn, her executor, former research assistant and the founder of the Hannah Arendt Center at The New School in Manhattan. He was particularly adamant about accusations that she was a “self-hating Jew.”

Hannah Arendt biographer Samantha Rose Hill stands in front of one of the late writer’s former residences on New York’s Upper West Side. (New York Jewish Week)

In a collection he edited of Arendt’s Jewish writings, Kohn insisted that her experience as a Jew — as a target of antisemitism in her youth, as a German Jew left stateless, as a supporter of a Jewish nation in Palestine, (albeit a binational state of Jews and Arabs) — “is literally the foundation of her thought: it supports her thinking even when she is not thinking about Jews or Jewish questions.”

In his book about Arendt’s notion of “solidarity,” Kim, a professor in the department of European Languages and Transcultural Studies at the University of California, says Arendt’s perception of how the world failed the Jews shaped her thinking on liberation for other oppressed peoples — and not always for the better. While she considered herself what today we might call an “antiracist,” by the late 1960s she was wary of the Black Power movement and rejected the idea of assigning collective guilt to white people for the evils of slavery, Jim Crow and lingering racism. Her resistance to the militant wing of the civil rights movement, writes Kim, “tells the story of Arendt’s imperfect love for the world.”

And yet in death Arendt seems to have gotten the last word: Beginning with the rise of Donald Trump and the resurgence of real and would-be autocrats from Venezuela to Hungary to Russia, her works are back in fashion. Even her poems — published together for the first time in the new collection — reflect preoccupations that seem of the moment: alienation, loneliness, the feeling of being a refugee, the terror of living under totalitarianism and a way of thinking free of ideological orthodoxies.

And yet Hill, the editor of the poetry collection, cautions against relying on Arendt as a sort of intellectual guru. At a conference in November, she even suggested “it’s time to put her back on the shelf.”

“We live in a radically different time today, and I think that requires a new form of analysis,” Hill, a professor at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, told me. “I think that to try to divine what is happening right now through her work is a sort of misdirection, and it can lead to a kind of looking away from reality, which is the very thing that she cautioned us against.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.